Consider the case of Lexius Saint Martin. He’s the Waterville resident, now 35, who was arrested by federal immigration officials on Jan. 2, and, despite public rallies on his behalf, deported to Haiti last week, where he hasn’t lived since he was 11 years old.

Saint Martin’s family came to this country as refugees, and became legal residents but not citizens; naturalization is an arduous and demanding process. Then, he made a mistake. He was convicted of selling cocaine in 2008 and served seven months in jail.

With the opioid epidemic all around us, most Mainers are keenly aware our drug laws aren’t working. We seem less convinced about our immigration laws, but they aren’t working, either.

Under the Trump administration, we’re employing a new form of Prohibition against people whose offense is that they were born in other countries. The problem isn’t new, but has reached a new virulence as a sitting president condemns whole nationalities and religions — “Mexicans” and “Muslims” — based on some imaginary standard of “Americaness.”

Not since the 1920s has there been such a sustained attack on a basic liberty Americans bestowed on themselves, and the world — equality under the law. Citizens are entitled to second chances following a criminal conviction: probation, parole and a chance for reintegration into the community.

Non-citizens are denied those chances. Lexius Saint Martin, after serving his sentence, was ordered deported in 2008, but the order was stayed because of Haiti’s catastrophic earthquake.

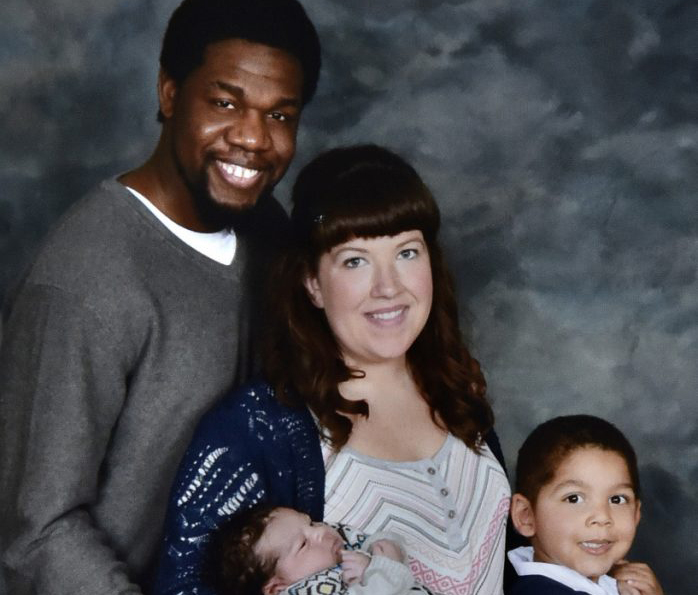

Over the next decade, Saint Martin married, had two children with his wife, Mindy, with a third on the way. He worked steadily, started his own cleaning business, and was doing exactly what he was supposed to do, including checking in with immigration authorities.

Then Donald Trump took office. One day, Saint Martin was in Waterville, then he was gone, with no right of appeal, separated from his family without any likelihood of reuniting on American soil.

For some, Saint Martin’s deportation may seem like just applying the rules differently; American presidents have enormous discretion when it comes to immigration. But it also illustrates one of the ugliest strains in our history, one parallel to, but separate from, the grim legacy of slavery.

The decisive turn toward “nativism,” however unlikely that might seem in this nation of immigrants, came in 1924, when President Calvin Coolidge signed the National Origins Act, which — after three centuries of free passage to this continent — limited legal immigration to just 150,000 people a year.

It gets worse: Some 70 percent of potential new citizens had to come from just three countries: Germany, Britain and Ireland. Not only were Asians and Africans completely excluded, but there were minuscule quotas for most of Europe, including Italy, Greece, Spain and France, and, in North America, Canada.

The latter restrictions had profound effects on Maine, where tens of thousands of French Canadians had emigrated to staff booming mills in Lewiston, Rumford, Biddeford, Augusta and elsewhere. Suddenly, families that lived on both sides of the border were divided, permanently.

It’s no coincidence that the 1920s saw rising religious bigotry, with the Ku Klux Klan burning crosses in Portland, Lewiston and Rumford. Their targets were not blacks, but Catholics — especially French Canadians.

The law was the product of then-fashionable theories of “eugenics,” which held that “superior races” would “degenerate” if they married “inferior” southern Europeans — a theory with no scientific basis. Nazism under Hitler discredited “eugenics,” but the National Origins Act lasted two decades beyond World War II.

It ended only with a nearly forgotten act of statesmanship by President Lyndon Johnson, who in 1965 signed the bill that abolished national quotas. In the half century since, this has created a far more diverse nation that established reservoirs of goodwill around the world, on every continent, that still exist, however depleted they may seem.

In words recalling his eloquent speeches about civil rights, Johnson said that abolishing national quotes meant they “will never again shadow the gate to the American nation with the twin barriers of prejudice and privilege.” And in words that now seem ironic, he said the new law would make the nation “feel safer and stronger . . . in a world as varied as the people who make it up.”

The 1965 immigration law is less remembered that Medicare and Medicaid, Model Cities or — of course — Vietnam, but may in the end accomplish more than any other Great Society legislation. It mounts a powerful challenge to the thinking behind the National Origins Act, and to the current president, too.

For as long as community members like Lexius Saint Martin disappear from among us, freedom does not ring.

Douglas Rooks has been a Maine editor, opinion writer and author for 33 years. His new book, “Rise, Decline and Renewal: The Democratic Party in Maine,” will be published next month. He lives in West Gardiner, and welcomes comment at: drooks@tds.net

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.