Congress has found a small way to skirt campaign spending laws — just call it “franking.”

Franking is the system by which members of Congress send mass mailings to constituents — a “frank” refers to the use of a member’s signature for postage rather than a stamp.

The practice dates back to the First Continental Congress and comes with the best of intentions; it is undoubtedly in the public’s interest to hear from their representative in Washington.

But in practice, congressional mailings are just campaign materials by another name.

In that way, they are a lot like “issue ads,” in which dark-money organizations can mention a candidate — and keep their donors secret — as long they don’t expressly advocate for the candidate, even though that is clearly the purpose.

Similarly, with their mass mailings, members of Congress aren’t allowed to openly campaign. They can’t make partisan points or criticize colleagues. They can’t explicitly ask for votes.

But, just as in issue ads, they can push the rules to the limit, promoting themselves in a way that meets the letter of the law but not the intent. Instead of informing constituents of nonpartisan events in their district, or responding to direct questions from voters, member of Congress can, for instance, send out unsolicited letters extolling their hard work and values, complete with the same spin and hyperbole that dominates political advertising.

And members largely don’t send these materials consistently through the year. Instead, the mailings are concentrated in the third quarter of election years, so that they arrive in mailboxes as close to the election as possible while still following the rules — the law says nothing can be sent within 90 days of the November vote.

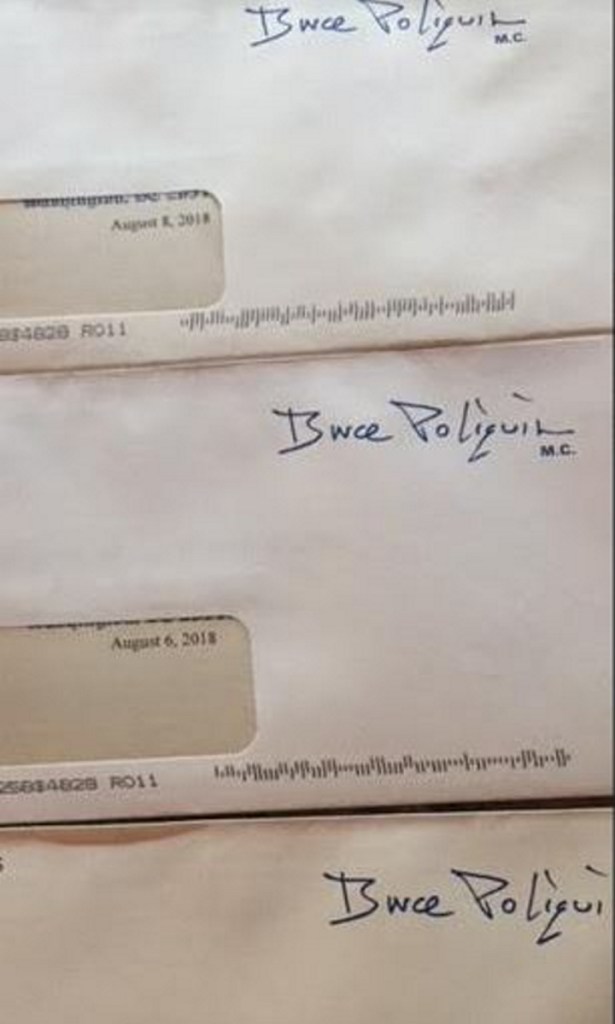

Rep. Bruce Poliquin, R-Maine, for instance, spent more on franked mail in the final six weeks before the deadline for the 2016 election than in all other quarters combined, according to an analysis by Steve Collins of the Lewiston Sun Journal. He appears to be following the same script in the lead up to the 2018 election, as a number of Mainers reported receiving unsolicited letters from the congressman before the Aug. 8 deadline.

A Poliquin spokesman told the Sun Journal that the mailings are necessary to communicate with constituents in “one of the most elderly and rural districts in the nation.”

That may be true, but it doesn’t explain why Poliquin’s spending on mail is so concentrated in the time immediately before he’s up for election.

No honest person can dismiss the connection between franked mail and campaigning, particularly when you consider which members spend the most on mailings.

In the six weeks before the 2016 deadline, as he faced a tough challenge in his first re-election race, Poliquin spent $150,000 on franked mail, the most of any other member of Congress.

And an analysis by Roll Call found that House members in competitive districts, regardless of party affiliation, spend almost three times as much money on franked mail than members in uncompetitive races — taxpayer money that is, obviously, not available to their challenger.

If you’re keeping score at home, that means franked mailing is used to promote, often disingenously, the accomplishments of an elected official. It is used most often in the lead up to an election by members of Congress facing a tough opponent, when every bit of promotion helps.

That sounds an awful lot like campaign spending, not matter what you call it.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.