U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ description of college students as “sanctimonious, sensitive, supercilious snowflakes” might just be the best example of alliteration from a government official since Vice President Spiro Agnew called the news media “nattering nabobs of negativism.”

But the clever use of words doesn’t necessarily reveal the truth.

Students who will return to college campuses in the coming weeks are from a generation that has experienced an extraordinary course of events over their short lifetimes. Their childhoods were shaped by the Sept. 11 attacks and the greatest economic challenge this country has known since the Great Depression. They are also the first cohort to grow up with social media.

The odds of a generation emerging from those circumstances fragile and pompous, as Sessions portrays them, are low.

Of course, how today’s college students will think and behave when they reach midlife is beyond the capabilities of our crystal ball.

But from our vantage point as longtime educators, we can offer an alliteration of our own about who they are now: caring, complex, committed and clear-eyed.

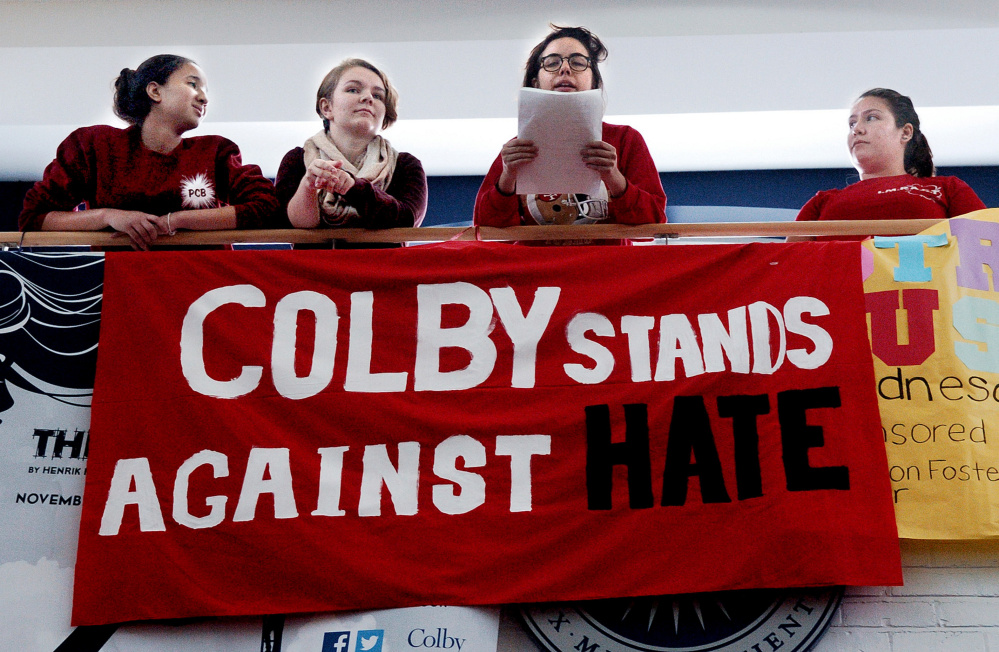

Witness how comfortable they are with difference. Fears and hatreds that have plagued this nation from its founding are unacceptable to today’s college students.

They have trouble understanding prior generations’ obsession with differences in sexuality and sexual expression, in race and ethnicity, and in gender.

Gay or straight? Black or white? Male or female? They reject labels and dichotomies and how they’re used to oversimplify and do harm.

Do we know students so arrogant and hypersensitive that they resemble popular stereotypes of their generation? Sure we do; they typically come from doting parents and school administrators who celebrated them ceaselessly and, as the cliche goes, gave them the same size trophy for coming in last as for coming in first. (But who’s to blame for low standards? Obviously the people who set those standards, not their children.)

Strikingly, though, even the worst of today’s college students tend to be more caring and respectful of others than were their egotistical counterparts of an earlier generation, who put advancing their careers above everything.

Which is not to say that we see nothing that concerns us in present-day college students. Their clear-eyed, accepting outlook, while a model for the rest of us in some domains, leaves them disturbingly passive in others.

During a recent class session, one of us suggested that we have given up our privacy rights in order to protect our safety. The government, with good intentions or bad, has stepped up surveillance in the name of security. In the past, this argument has sparked some spirited discussion. Not this time.

One student said that the very notion of privacy was an illusion cherished by technologically naive adults. “Don’t you know,” he said, “that not just the government, but companies are monitoring our every move?” It is impossible, he concluded, to protect something that doesn’t even exist.

In a follow-up discussion, the poor old professor posited that after the students experience the harsh reality of having their digital footprints evaluated by potential employers, they will rethink their attitudes about keeping some things private. But a student replied that they all have embarrassing things online, so who are employers going to hire?

We’re dubious about those claims and will continue to implore students not to give up on protecting their own and others’ privacy. But this generation of college students is far from the caricature posited by the attorney general. They came of age in a time of challenges, and they already recognize what today’s world is about and embody much of what is best in it.

Maybe it’s us elders who are the sanctimonious snowflakes. We’ll close with a reference from Sessions’ college years: As the Who put it in “My Generation,” we ought to stop trying to put them down.

Barry Glassner is a professor of sociology and former president of Lewis & Clark College. Morton Schapiro is a professor of economics and president of Northwestern University.

©2018 Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.