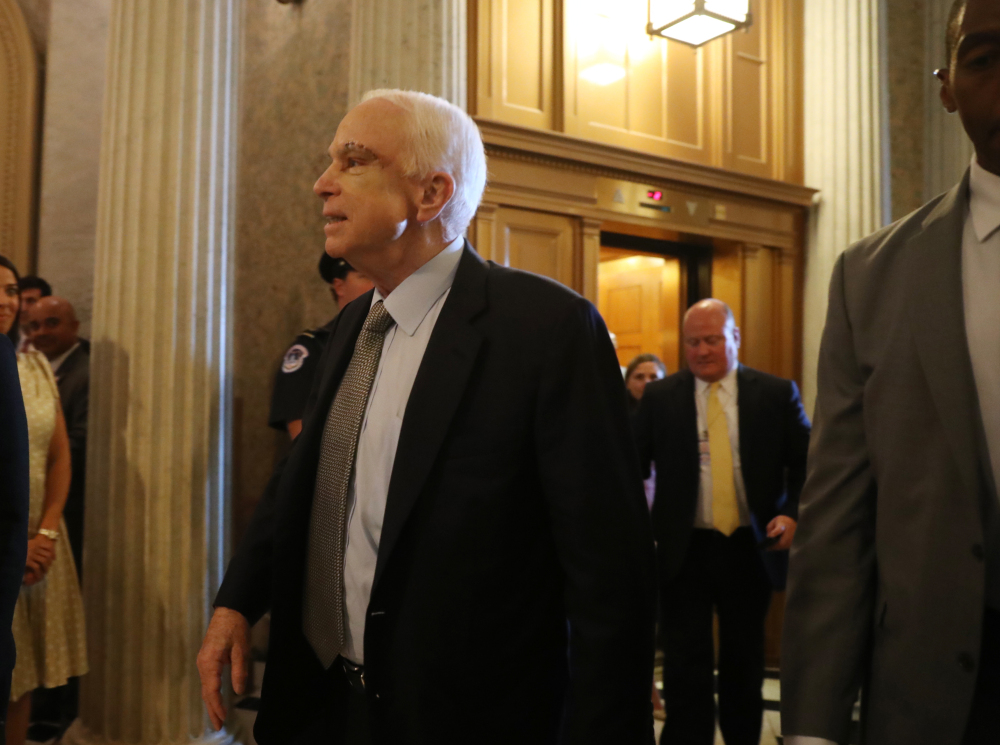

A few days before casting the vote that kept Obamacare intact in the face of a GOP attack, Sen. John McCain, the Arizona Republican who died last week after a yearlong battle with brain cancer, gave a speech that his colleagues should heed if they want to find their way out of the wilderness they’ve blundered into.

“Let’s trust each other. Let’s return to regular order,” McCain said, referring to the process of holding hearings and working in committee to improve legislation before passing it into law. “We’ve been spinning our wheels on too many important issues because we keep trying to find a way to win without help from across the aisle. That’s an approach that’s been employed by both sides, mandating legislation from the top down, without any support from the other side, with all the parliamentary maneuvers that requires. We’re getting nothing done.”

Although he never achieved his ambition to be elected president, McCain was an enormously consequential figure in the Senate, despite his reputation as a maverick. His voting record shows him to be a solidly conservative Republican, and a hawkish one at that. But his willingness to cross party lines and bridge differences was as much his signature as his outspokenness and occasional bursts of temper.

We are a polarized society, with potentially unbridgeable differences on many issues. But McCain was right: When the two major parties cannot work together to find common ground, our problems fester.

Many of the tributes to McCain have focused, appropriately so, on his personal qualities — his patriotism, his willingness to admit error, his personal decency, his readiness to engage with critics and the press.

Inevitable contrasts are also being drawn between the senator who wanted to be president and the reality TV star who actually is president, a man who avoided the draft during the Vietnam war through medical and educational deferments and who once disparaged McCain’s heroism as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam. (“I like people who weren’t captured.”)

Whereas Donald Trump rode to political prominence by questioning whether Barack Obama was born in the United States, McCain famously corrected a voter who announced at a town hall meeting that “I can’t trust Obama” because “he’s an Arab.” McCain responded: “No, Ma’am. He’s a decent family man (and) citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues, and that’s what the campaign is all about.”

McCain is also being remembered for substantive positions that put him at odds with some in his party, including his support for immigration reform, limits on special-interest money in political campaigns and an end to the use of torture in the interrogation of suspected terrorists.

But the image of McCain the maverick can’t obscure the fact that he was an advocate and practitioner of the sort of consensus politics that seems to be vanishing in the Senate. To his credit, McCain took steps to try to reverse the erosion in bipartisan comity. Yet his accomplishments on that front are proving to be ephemeral.

For example, after Democrats in the Senate filibustered some of President George W. Bush’s judicial nominees in 2005, McCain was the leader of an effort by a bipartisan group of senators known as the Gang of 14 to allow some nominees to receive votes. The deal headed off a threat by Republicans to trigger the “nuclear option” and abolish filibusters for judicial nominations.

The partisan wrangling over judges eventually picked up steam again, however, leading Senate Democrats to abolish filibusters for all nominees except Supreme Court justices in 2013. Four years later, after refusing to hold even a hearing on Obama’s last Supreme Court pick, Senate Republicans killed the filibuster on Supreme Court nominees as well.

In 2010, McCain warned Democrats against using the budget reconciliation process to approve elements of the Affordable Care Act by a simple majority vote, predicting that it would fundamentally alter the nature of the Senate. Sure enough, Republicans used reconciliation this term to try to repeal the ACA, and have mulled deploying it for other highly partisan proposals as well.

The senators now giving tribute to McCain should revisit the warnings he’s given over the years about the consequences of polarization and the recurring cycle of partisan payback. Sadly, there’s no indication that they’re willing to take his advice to heart.

Editorial by the Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.