WASHINGTON — Moist air, warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico, and ideal wind patterns supercharged Hurricane Michael in the hours before it smacked Florida’s Panhandle.

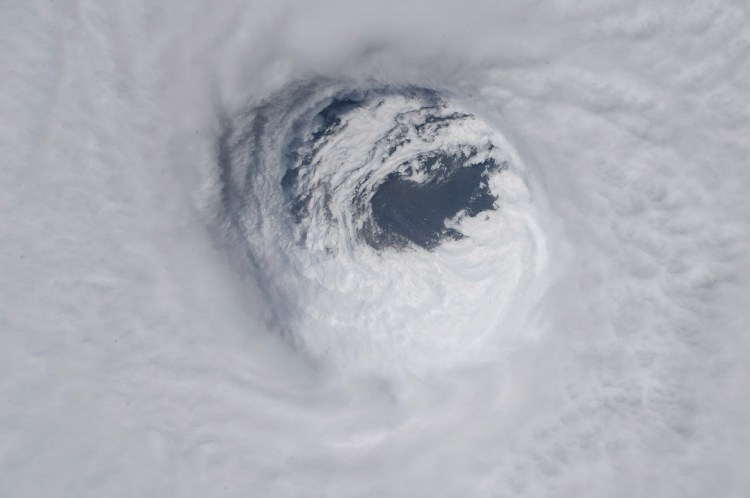

Michael was barely a hurricane Tuesday morning, with winds of 90 mph. A little over a day later, it had transformed into a monster. When it made landfall Wednesday, it was blowing at 155 mph. That’s a 72 percent increase in wind speed in less than 33 hours.

“Michael saw our worst fears realized, of rapid intensification just before landfall on a part of a coastline that has never experienced a Category 4 hurricane,” University of Miami hurricane researcher Brian McNoldy said.

Hurricanes have something called a potential intensity. That’s how strong a storm can get if all other factors are aligned, NOAA climate and hurricane expert Jim Kossin said. Michael had nothing holding it back.

“Everything was there for it to reach its potential and it did,” Kossin said.

The science is clear on how a warmer climate makes for nastier hurricanes. They are wetter, possess more energy and intensify faster, something Michael demonstrated this week and Florence showed last month.

But determining the role of global warming in a specific storm is not so simple – at least not without detailed statistical and computer analyses.

Last month, the Associated Press consulted with 17 meteorologists and scientists who study climate change, hurricanes or both. A few experts remained cautious about attributing global warming to a single event, but most saw the hand of humans playing a role in Florence.

Global warming didn’t cause Florence, they said. But it made the system a bigger danger.

Global warming didn’t cause Florence, they said. But it made the system a bigger danger.

“Florence is yet another poster child for the human-supercharged storms that are becoming more common and destructive as the planet warms,” said Jonathan Overpeck, dean of the environment school at University of Michigan.

Over the past few years, the new field of attribution studies has allowed researchers to use statistics and computer models to try to calculate how events would be different in a world without human-caused climate change.

A couple of months after Hurricane Harvey last year, studies found that global warming significantly increased the odds for Harvey’s record heavy rains.

“It’s a bit like a plot line out of ‘Back to the Future,’ where you travel back in time to some alternate reality” that is plausible but without humans changing the climate, said University of Exeter climate scientist Peter Stott.

A National Academy of Sciences report found these studies generally credible. One team of scientists tried to do a similar analysis for Florence, but outside experts were wary because it was based on forecasts, not observations.

As the world warms and science advances, scientists get more specific, even without attribution studies. They cite basic physics, the most recent research about storms and past attribution studies and put them together for something like Florence.

“I think we can say that the storm is stronger, wetter and more impactful from a coastal flooding standpoint than it would have been BECAUSE of human-caused warming,” Pennsylvania State University climate scientist Michael Mann wrote in an email. “And we don’t need an attribution study to tell us that in my view. We just need the laws of thermodynamics.”

As for Michael, the same dynamics could be seen.

“Have humans contributed to how dangerous Michael is?” Kossin said. “Now we can look at how warm the waters are and that certainly has contributed to how intense Michael is and its intensification.”

The warm waters, Kossin said, are a “human fingerprint” of climate change.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.