Some central Maine communities are taking action to try to eliminate nonrecyclable items from the recycling stream including Augusta, where a resident was issued a summons after allegedly putting a nonrecyclable item into a bin and refusing to take it out.

In Manchester, there are plans to remove the town’s only publicly accessible recycling bin, while residents of Readfield, Wayne and Fayette may have limited access to a recycling bin and what goes in.

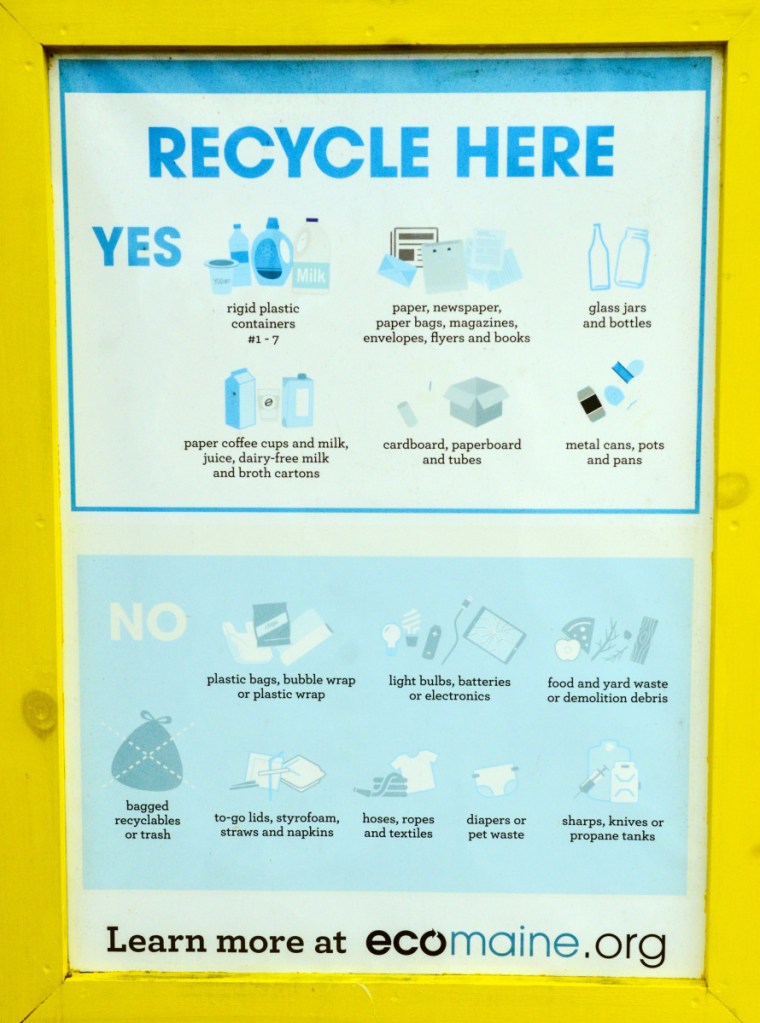

The steps communities are taking to keep nonrecyclable items out of their recycling collection bins are in response to dramatic changes in the international market for recyclable materials, primarily China no longer taking paper from other countries. Changes in the market for recyclable materials prompted single-sort recycling processors, including ecomaine in Portland, to clamp down on contamination in the loads of unsorted recyclables it gets from numerous municipalities across the state. The company now charges additional fees for loads containing more than 6 percent nonrecyclable materials.

In turn, municipalities looking to avoid the additional cost from those fees are taking steps to reduce the amount of nonrecyclable items put in the bins residents use to dispose of their unsorted recyclable items.

Manchester officials, unless they find a solution by the end of the year, plan to eliminate the collection bin kept outside the town office for residents to put their recyclable items into.

Some Augusta city councilors said this week they want the city to dump its single-sort recycling program which provides three single-sort recycling bins at different locations for residents to use.

Last month, Augusta moved one of its recycling bins from the Buker Community Center parking lot, where it was largely unmonitored, to a parking lot just outside the police station, in hopes the police presence would deter residents from putting nonrecyclable items into the bin.

Within weeks of that bin being moved to an Augusta man, police said, was seen by a police department employee putting nonrecyclables into the bin. Police asked the 44-year-old man, Craig Colby, to remove the nonrecyclables, which Behr declined to identify, and said if he did so he would only get a warning, according to Sgt. Christian Behr. He refused, Behr said, and was charged with theft of services on Sept 21.

Colby could not be reached for comment for this story and no phone number was listed for him in Augusta.

Lesley Jones, public works director in Augusta, said increased monitoring of the bins and moving the bin from Buker to outside the police station have reduced the amount of nonrecyclables contaminating Augusta’s recycling bins.

On average the percentage of contaminants in bins sent from Augusta to ecomaine for processing has decreased to below the 6 percent cutoff above which municipalities are charged fees which ranges from $35 per ton for loads with 6- to 10-percent contamination, up to $65 per ton for loads with 26 percent or higher. That percentage varied between 1.5 percent and 1.75 percent each week of September, according to data supplied by ecomaine.

Prior to the city and ecomaine stepping up efforts to educate users what should, and shouldn’t, go into the recycling bins, about one of every five bins the city sent to ecomaine had more than the acceptable amount of recyclables and was subject to an additional fee.

Despite the improvements in Augusta’s contamination rates, some city councilors said during a wide-ranging discussion of recycling Thursday night they think the city should get rid of its three recyclable collection bins at the police station, Augusta City Center and the Public Works Department, leaving only a single-sort recycling bin at Hatch Hill landfill, which the city shares with several surrounding municipalities which pay fees so their residents’ waste can be sent to Hatch Hill.

At-Large Councilor Corey Wilson said the $57,000 net cost of the single-sort recycling bins is too expensive and said he believes having Augusta’s recyclables hauled to Portland for processing may have a bigger negative impact on the environment than would simply throwing the items collected into the landfill.

“I think that it’s harming the environment, in our case, to recycle, quite frankly,” Wilson said. “I hate the whole thing, I’m being very clear, I’d like to get rid of it. And I think we could spend $50,000 on hiring another school teacher or something else that we need in our community and there would be no harm to the environment. And there would still be recycling for people who want it, they’d just have to drive to Hatch Hill.”

City Manager William Bridgeo said whether to fund the program beyond this year will be taken up in about four months as part of discussions over next year’s proposed city budget.

Ward 1 City Councilor Linda Conti said the best thing residents can do to help the environment is to not buy so many plastic items to begin with. She also said the city should ban plastic bags.

Maine municipalities including Manchester have banned plastic bags from most retail stores within their borders, and residents of Waterville will consider a controversial proposal to ban plastic bags from big-box stores in November.

Augusta Mayor David Rollins said he’d heard a radio news report recently which indicated more than 60 percent of items collected nationwide for recycling end up, instead, in landfills. He said the report also noted America, because it was able to send most of its recyclable paper to China for processing until recently, has never really undertaken what to do with the recyclable items produced here.

Matt Grondin, communications manager for ecomaine, said the landfill numbers cited by Rollins are inaccurate.

He said ecomaine, which also runs a waste-to-energy incinerator, doesn’t landfill anything, other than ash produced by the incinerator. Nor does it put any recyclable items into the incinerator. Anything recyclable that is sent to ecomaine, he said, is recycled.

But he agreed with Rollins’ thoughts about the need for the United States to examine how it recycles.

“This recycling market crisis has precipitated a new way of thinking about recycling in terms of domestic production,” Grondin said. “We’re seeing a lot of businesses and organizations looking at opportunities for domestic recycling. That’s a great silver lining out of all of this, it’s forced us to examine the way we’re recycling.”

Grondin said China is still not accepting paper from the United States but the market for recyclable paper has improved somewhat. The nonprofit company still has to pay to get rid of recycled paper, but the cost per ton to do so has decreased, from around $50 to $60 a ton a few months ago to around $10 to $20 per ton. He’s optimistic the cyclical recyclables market will, at some point in the future, see paper return to being something that can be sold after it is processed.

The market for other recyclable materials, such as metal and plastics, is stronger, and ecomaine receives revenue from the sales of recyclable materials other than paper.

E. Patrick Gilbert, town manager in Manchester, said for now the town plans to get rid of it single-sort recycling bin at the end of the year when its contract with ecomaine runs out. He said the cost of paying contamination fees, if the program continued, would amount to more than the town has budgeted for recycling.

He said Manchester’s contamination rates have recently decreased to as low as 3 percent for some loads, down from a few months ago when some loads reached as high as 30 percent contamination.

He said town officials aren’t sure what Manchester will do for recycling next year. He said residents can use the single-sort recycling bin at Hatch Hill in Augusta, because Manchester is a member community of the landfill.

Jan Tricarico throws a cardboard box into the recycling bin on Friday at the Readfield Transfer Station.

In Readfield, where a single-sort recycling bin at the staffed transfer station is also used by residents of Wayne and Fayette, no loads with unacceptable amounts of contamination have been sent to ecomaine since June or July, according to Readfield Town Manager Eric Dyer, who is also manager of the transfer station.

Dyer said the town hired part-time staff for the summer to educate users on what is allowed into the recycling bins and what is not, and the town and ecomaine also made other educational efforts including providing written materials and access to an app, Recyclopedia, so users know not to put nonrecyclables into the bin.

And an attendant at the transfer station, whose booth is only about 40 feet away from the recycling bin, monitors use of it to make sure people don’t pitch nonrecyclables in. The bin is only accessible on the four days of the week the transfer station is open, unlike Manchester’s bin and two of Augusta’s which are accessible 24-hours a day, seven days a week.

“We have staff right there that can help educate and address any issues, sometimes they pull plastic bags out of the hopper,” Dyer said. “We’re not in a bad spot because we’re able to control the contamination. We really appreciate all the effort residents have made, over the last six months, to curb contamination rates.”

Keith Edwards — 621-5647

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story