When I learned to drive, the highway speed limit was 55 miles per hour.

But as soon as I got my license, I found out that you could get killed if you tried to drive that slow. The real speed limit was set by the other drivers on the road and it was somewhere between 65 and 70. As long as you didn’t drive 75 or 80, you didn’t have to worry about getting a ticket.

That’s how corruption works, too. It’s contagious. Once it looks like everyone is bending the rules, it becomes impossible to stop. People who are otherwise honest feel that they have no choice but to get into the action.

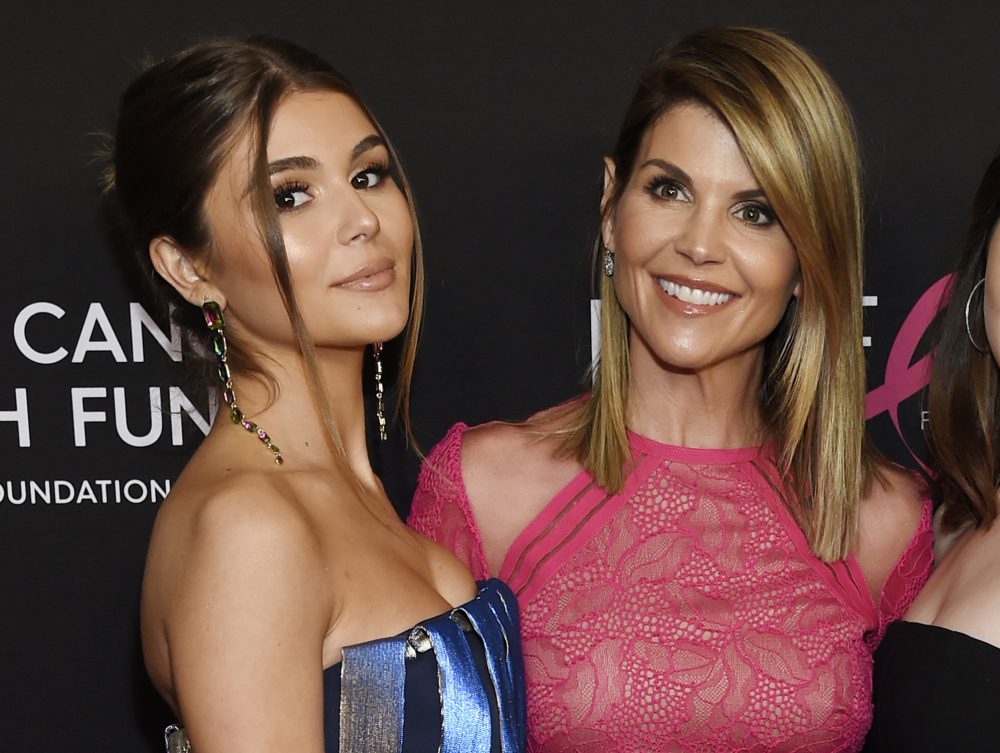

Long before hearing that wealthy parents had been indicted on charges of cheating to get their kids into elite colleges, I’ve felt that there is something wrong with the admissions process. It’s a corrupt system that allows powerful people to transfer class advantage from one generation to another by disguising it as merit. It’s like money laundering for privilege.

Everybody knows that the super-rich can pay for a building or two to make sure that there’s a spot in the freshman class for their son or daughter — even in the most selective schools, even with the least impressive kids. But few of us talk about how many people in the middle class believe that it’s OK to buy a little edge for their own children.

SAT prep and help with essays is commonplace in some circles. Kids are encouraged to pad their resumes. Parents keep track of the insanely complicated admissions and financial assistance deadlines, filling out confusing aid applications for the kid playing “Fortnite” in his bedroom.

But the majority of parents — those who never went to college and don’t know a FAFSA from an ACT — depend on overworked high school guidance counselors to usher them through this gateway to the middle class. Chances are, most of those students will never apply to college, and very few of the ones who do will get into the highly selective, brand-name schools known to every HR director in the country when it’s time to hire.

Even when no one is breaking the law, this confusing process gives the in-the-know families a huge advantage. Is it fair? No, it is not. Do you want to sacrifice your child’s future on the altar of fairness? Eh, maybe you’ll just write a check to the scholarship fund.

So, the biggest surprise to emerge from the scandal may be how few people are actually surprised that this kind of thing is going on.

The crimes these wealthy parents are accused of committing — bribery and fraud — are only marginally worse than what other families do every day. It’s like getting pulled over for going 100 in a 55 mph zone, while everyone else cruises by at 70.

These parents shelled out plenty, millions, in some cases, and they will have to pay a lot more now to defend themselves in court.

And for what? Did they want their kids to have a good education?

Hardly. Schools like Harvard and Stanford give away their lectures for free online. There’s no special sauce in the classroom that will prepare this group of already rich young men and women for the world they’ll enter with tremendous advantages.

Are they doing it for the social connections their kids would make at a famous school? Maybe, but that would be true wherever they went. The dirty little secret is that there are worthwhile people everywhere.

What was so important about sending these already elite children to these elite schools that made these parents willing to spend a fortune and risk going to jail?

We should read their actions as an admission that these highly successful people from a variety of competitive fields don’t believe that there’s such a thing as equal opportunity. They seem to understand that despite our egalitarian talk, the best way to get to the top is to start very near the top.

That makes a degree from an elite university less a badge of achievement than a birthright that gets passed from one generation to the next, the way that a duke’s son gets to be duke next.

That diploma lets you wear a class ring or a sweatshirt, telling the world that you are extraordinary and that you deserve the high place you hold in the meritocracy, whether or not it was your merit that got you there.

Indicting this group of parents has started a good conversation about inequality.

But it won’t change this corrupt system until most people, including those of us who have benefited from it, call it what it is.

Greg Kesich is the editorial page editor at the Portland Press Herald. He can be contacted at: gkesich@pressherald.com

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.