HEAD TIDE — For decades, springtime high water flowing through the Head Tide Dam on the Sheepscot River has kept species of migrating fish pinned in the pool below the dam.

The speed and volume of the water flowing through two openings in the dam is high enough that shad, Atlantic salmon, alewives and other species of river herring can’t move upstream through that velocity barrier to their spawning grounds until the flow abates.

“The fish try to get through and get knocked back,” said Andrew Goode, vice president of U.S. Operations for the Atlantic Salmon Federation. “There’s a daisy chain circle, and they just go around and around until the velocity drops.”

That’s expected to change now that work has started on a project that will open up fish passage on the river that flows for about 66 miles from its headwaters in Freedom to its outlet in Georgetown.

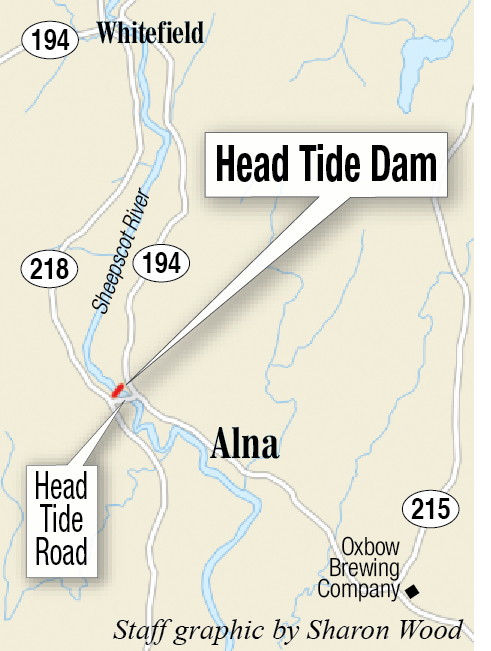

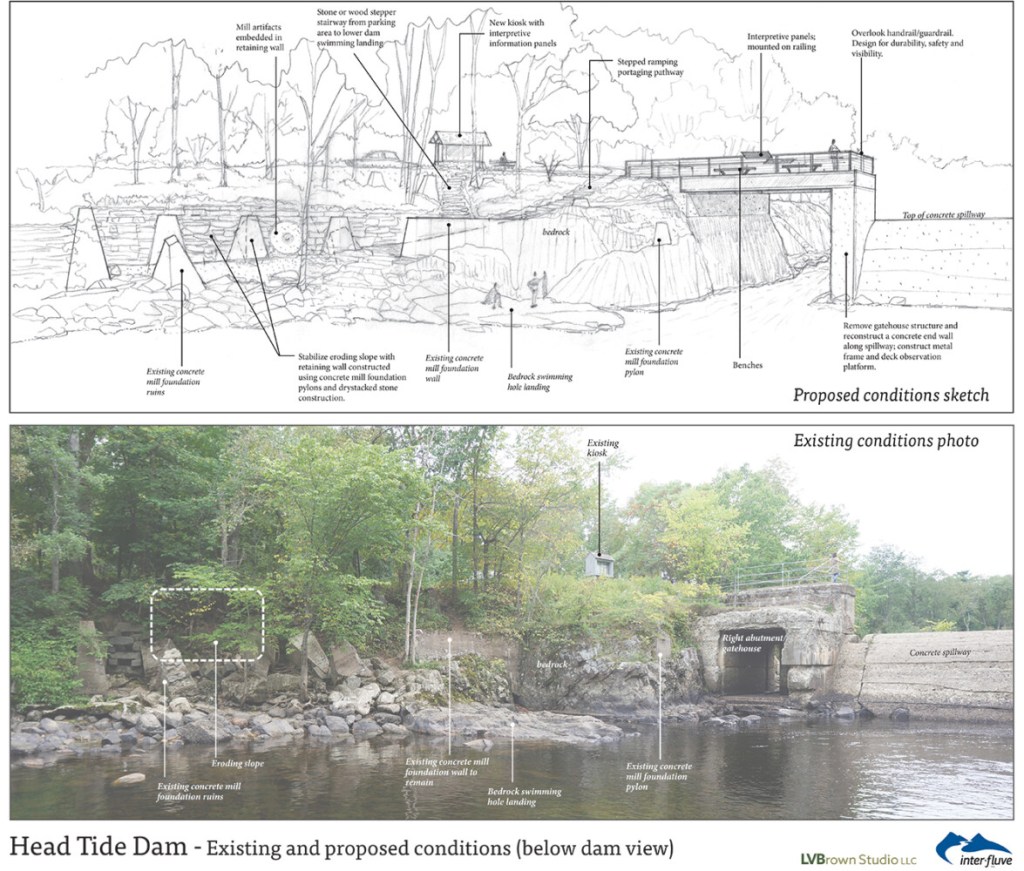

For the next two months, the dam site — located only a hundred feet or so upstream of the bridge where Head Tide Road crosses the river in the historic Head Tide village — will undergo reconstruction. The project includes opening up a 23-foot section of the dam’s south end, installing a new observation platform over that opening and developing the parking area just off Head Tide Road, as well as a path down to the river.

The work in north Alna means access to the site, including the swimming hole just downstream from the dam, will be closed while the work is being completed.

Sumco Ecological Contractors were awarded the bid for the work, Goode said, and it will be using local subcontractors to complete the work.

Last week, trees were removed from around the parking lot and along the southern bank of the river. This week, Goode said, the large equipment required for the project will be moved on site. Work is expected to start in earnest in the last two weeks in July.

The project, estimated to cost about $500,000, is being paid for through federal funds from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and money contributed by the Wildlife Federation and raised by the Atlantic Salmon Federation, Goode said.

Just about a year ago and a dozen miles upstream in Whitefield, the 200-year-old Coopers Mills dam was removed as part of the initiative to open up the Sheepscot for fish migration. Voters agreed to the removal at Whitefield’s 2016 Town Meeting. Next year, work is expected to get underway at Branch Pond to improve fish passage over the dam that impounds the lake.

They are all part of a larger watershed initiative that the Atlantic Salmon Federation, the Midcoast Conservancy and the Nature Conservancy have been working on.

“We want to reconnect parts of the river with the estuary and the Gulf of Maine,” Goode said.

This year’s project is not the first work to be done on the dam, he said. About five decades ago, an opening was made at the north end of the dam to allow Atlantic salmon to swim upstream.

“That was the only fish that people cared about in the ’50s and ’60s,” he said.

While other dams, like the one in Coopers Mills, have been removed to promote fish passage, that’s not an option in Head Tide.

Head Tide takes its name from its location at the head of tide, the farthest point upstream that is affected by tidal swings.

Its dam is listed on the National Register of Historic Places along with the rest of the village. But beyond that, when the town accepted the donation of the dam from its former owners, it came with the restriction that it could never be destroyed.

“Every one of these sites is different,” Goode said. “It depends on what the communities want. There’s a lot of local sentiment for the dam.”

In China, the dam is being preserved because it impounds a lake around which homes and camps have been built.

The work in Alna, approved by town voters in 2017, is taking place at a time of generally low water flow and when the migrating fish are no longer in transit.

What the river and the fish habitat will look like in the wake of this work is a bit of a mystery.

In the 1700s and 1800s, rivers were harnessed for the energy they could provide for industrial processes. At one point, the Sheepscot River powered six water wheels at Head Tide. But by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the mills had closed, with some being damaged in floods and others destroyed by fire. The last remaining mill was torn down in 1949.

The Head Tide dam was not the only dam on Sheepscot River. Not far upstream, the remnants of the dam at Kings Mills can still be seen in the river. Goode said Mother Nature and time have taken care of that dam and others.

“What we expect is the migration of the anadromous species that visit that river will now follow more natural rhythms,” said Mike Brown, a marine resource scientist with the state Department of Marine Resources.

Anadromous fish are those that migrate, like salmon and alewives.

“What we hope to see biologically is that these fish are able to migrate upstream and be more in tune with water temperatures and water flows that will make spawning more successful in the river and increase production,” Brown said.

Now, he said, fish have to wait downstream until the water velocities are low enough to travel upstream, and that can mean the spawning seasons are compressed because the water temperature is too high or the flow is too low.

“It’s been the way it’s been for such a long time; we’re not really sure what it’s going to look like,” Brown said. “We expect a very favorable response because now it’s going to operate more like a natural system.

“We’ll be measuring the change that results from these improvements,” he added.

The department already has a database of information collected on migrating fish on the Sheepscot, and it will be able to see how the populations change over time.

Goode said the Kennebec River is the best example of what can happen when a river is opened up. The 20th anniversary of the breaching of the Edwards dam was celebrated earlier this month.

The largest congregation of bald eagles in New England has been counted at the Sebasticook River, a tributary of the Kennebec, since the removal of the dam.

“That’s totally related to the restoration,” Goode said.

The work is not expected to have any impact on the flow of the river. Goode said sophisticated modeling has been used to understand the flows in the river.

“It won’t change the river downstream from the dam,” he said. “You are getting the same flow of water; it’s just coming through at a lower velocity.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.