Health care is again front-and-center in the presidential race, at least for Democrats. The debate is between those proposing a universal, “single payer” system, and those who prefer to build on the Affordable Care Act.

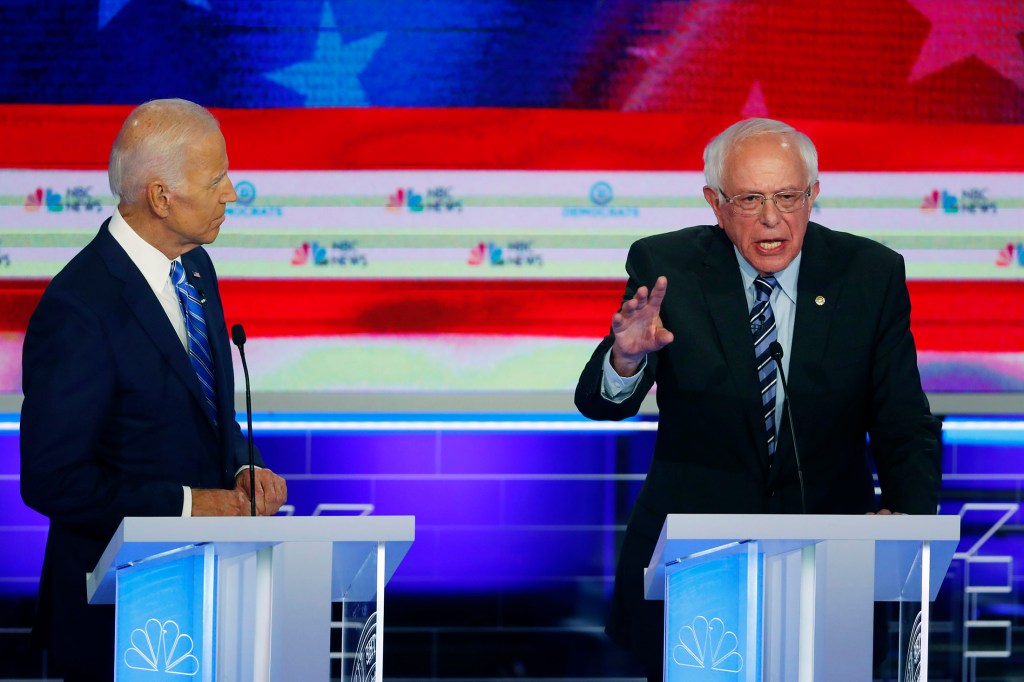

The plans getting the most attention have obvious flaws. Sen. Bernie Sanders, who campaigned on “single payer” in 2016, subsequently produced a Senate bill, “Medicare for All,” that basically provides everything for everybody, without regard to costs.

Sanders should have learned from his home state, Vermont, which rolled out a “single payer” initiative only to have it sink once costs of simply taking over the private insurance system became clear.

Others, including Joe Biden, want to preserve private insurance because — they say — most Americans are happy with their current plans, which hardly describes reality. Just say “high deductible,” and start listening.

Biden believes if we just expand Medicaid and subsidies on the insurance exchanges, and add a public option, all will be well.

It won’t. Though some accredited observers claim the ACA’s public-private system can work, because it does in Holland and Switzerland, it’s a false analogy.

Other national systems tightly regulated private insurance from the beginning, unlike the United States, where pretty much anything goes. And because health insurance is regulated here state-by-state, there are national insurers, but no national regulation.

The ACA was a valiant attempt, but experience shows private insurance is now more confusing and unpredictable than ever. True, insurers are no longer allowed to cancel policies retroactively or exclude millions for “pre-existing conditions” — but a permanent solution it’s not.

Still, though it’s easy — and politically popular — to blame private insurers (and the pharmaceutical industry) for all that ails us, these charges, too, miss the point.

We’re never going rein in our unbearable costs — 50% more than any comparable national system, and 100% more than the average — without focusing on how we provide health care, and how providers make decisions.

Maine’s a good example. As elsewhere, hospitals are the cost centers, directly or indirectly determining most health care we receive. Once, Maine’s three dozen acute care hospitals were all locally owned and managed; no more.

Hospitals have consolidated rapidly, and most are now owned by just two entities: Maine Health in Portland, and Eastern Maine (now Northern Light) in Bangor. The tragic failure of the state under former Gov. Paul LePage to provide Medicaid expansion pushed some small hospitals over the edge, but the trend was already well established.

Here’s the problem. The hospital companies that remain spend enormous amounts of money, public and private, with little accountability. They’re private institutions with no public access to board meetings; their annual reports are simply financial summaries.

We’ve gone from locally owned hospitals to a couple of health care giants — without any governmental oversight.

The federal government regulates hospitals primarily for patient safety; it has no ability to consider, let alone regulate, costs. Here, state government could play an important role.

Although taking over the insurance system is beyond any state’s capacity, doing something about costs and quality isn’t. Maine once had such a system, now virtually forgotten — which is surprising, because it actually worked.

The Maine Health Care Finance Commission was set up by Democratic Gov. Joe Brennan and run by Frank McGinty, later CFO for Maine Health. It grew out of the Medicaid crisis Brennan inherited on taking office in 1979; the Longley administration had left six months of unpaid hospital bills, literally stacked up in boxes.

The commission, though resisted by hospitals and, initially, Maine Blue Cross — back when we had a major non-profit insurer — solved the Medicaid problem by guaranteeing fixed monthly payments to hospitals.

In return, the hospitals had mandatory revenue caps, but were given flexibility to design programs as they wished. During the brief period the commission was in effect, Maine’s hospital costs were substantially below the national average, and quality actually improved.

When Republican John McKernan took office in 1987, the commission was abolished. Except for “voluntary caps” during the Baldacci administration’s Dirigo Health initiative, hospitals have been free to spend as much money as they like.

Could a new finance commission work? Absolutely. And given the ruinous escalation in all health care prices since the 1980s, it’s needed more than ever.

This time, a commission should be an independent agency, on the model of the Public Utilities Commission. Governor’s offices come and go, but the PUC is still with us a hundred years after its creation.

One of Gov. Janet Mills’s frequent campaign pledges was to “lower the cost of health care.” To do that, we need to do more than tinker. Effective hospital regulation will take time, so it’s essential we start now.

Douglas Rooks, a Maine editor, opinion writer and author for 34 years, has published books about George Mitchell and the Maine Democratic Party. He welcomes comment at drooks@tds.net

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.