February is named after the Roman festival Februa, rites of purification the Romans held in the middle of the month. Feb. 2, which we know as Groundhog Day, marks the halfway point of our winter season. Several interesting highlights this month are well worth braving the season’s coldest temperatures to see.

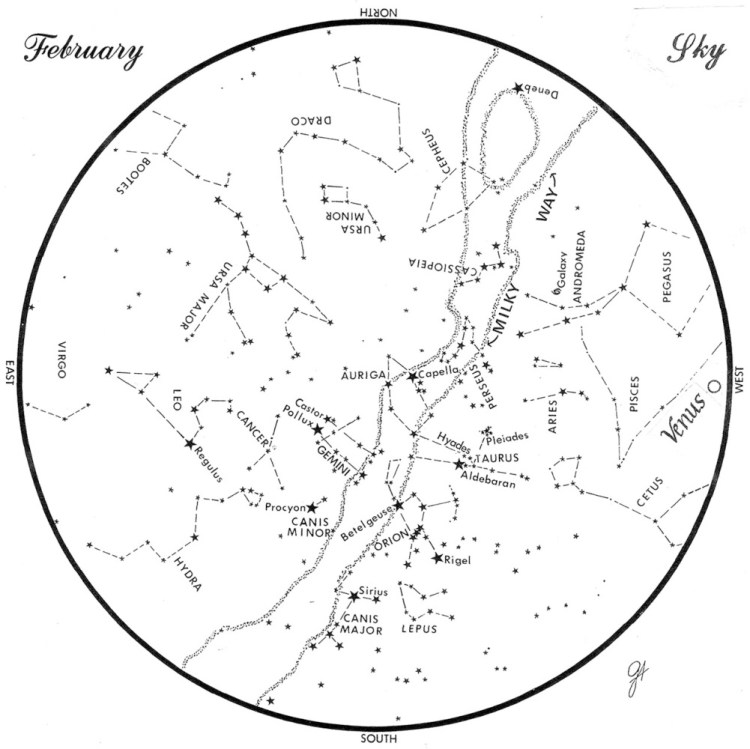

These include all five of our brightest planets crossing through the ecliptic plane of our solar system, three planets close together in the morning sky, several nice conjunctions with the moon and bright planets, a brightening comet in Perseus the Hero, and an occultation of Mars by the moon just after sunrise on Tuesday morning, Feb. 8.

Venus continues to climb higher into our evening sky each night as it is rapidly catching up with Earth in its faster, tighter orbit around the sun. Venus orbits at 22 miles per second, or 78,340 mph; and Earth orbits at 18.6 miles per second, or 67,000 mph. So not only does Venus orbit faster, it also has less distance to travel around the sun. One year on Venus is 225 days, and the radius of its orbit is only 70 percent of our radius, which is 93,000, 000 miles, or one astronomical unit. Venus spins so slowly that it is the only planet in our solar system whose day is longer than its year. Venus takes 243 days to make a single rotation, and it spins at only 4 miles per hour, compared to Earth at 1,000 mph near the equator.

By the end of this month, Venus will set nearly four hours after the sun, gaining nearly half an hour this month. Sometimes called our sister planet because it is the same size as Earth, Venus continues to get brighter each evening even as the sun illuminates it less. By the end of this month, it will be only 63 percent lit by the sun and will resemble a waning gibbous moon. Venus will be at its ascending node as it crosses through our ecliptic plane on the 15th.

Mercury makes a nice evening appearance below Venus in our sky during the first half of this month. Our first planet will reach greatest eastern elongation from the sun on the 10th. Mercury orbits at 31 miles per second, and its year lasts only 88 earth days while its day is 59 earth days. It also rotates slowly, at about 7 mph.

Mercury is the only planet whose entire elliptical orbit precesses a little as it orbits. The precession is only 1.5 degrees per century, but though it was noticed hundreds of years ago, it could not be correctly explained until Einstein came up with his Theory of General Relativity. It’s a testament to the enormous gravitational energy of the sun as it warps the very fabric of space-time around it, causing this slight precession of Mercury’s orbit. Classical Newtonian physics could never explain this effect, so astronomers thought another planet near the sun must cause the deflection. They named that imaginary planet Vulcan. Many scientists even thought they had seen Vulcan during total solar eclipses. Impossible because it does not exist – nor did it need to exist to explain this 200-year-old mystery. Mercury will be on its ascending node on the 7th.

The other three bright planets are all visible in the morning sky now. Mars is the highest, rising around 4 a.m., Jupiter rises around 5 a.m., followed by Saturn about half an hour later. All three are in the constellation of Sagittarius now and are moving in their normal, prograde motion. Each gets a little higher and larger in our sky each morning.

Mars is at its descending node on the first of this month, Jupiter will be there on the 26th, and Saturn on the 13th. Our three morning planets will reach their descending nodes this month, while our two evening planets reach their ascending nodes. If all the moons and planets orbited exactly in the plane of our solar system, we’d get many more eclipses and transits and occultations, but they don’t. Instead, they cross that plane moving upwards or downwards in their own rhythms and cycles.

However, we will get a fairly rare occultation of Mars by the waning crescent moon on Tuesday morning the 18th just after sunrise. Since Mars will have faded out by then, you will need a telescope to see it. Notice that Mars will fade out gradually as the moon covers it and then reappear gradually. When the moon occults a star, it blinks out instantly.

Even if you miss this occultation, this is a good time to think about humans returning to the moon and visiting Mars for the first time. NASA plans to go back to the moon by 2024, but it will probably be at least 10 years before we send humans to Mars. It’s important to go. If we found evidence of life on Mars, we would know that life could arise on at least two planets separately, which would mean many more planets in thousands of other solar systems are much likelier to also have some form of life. Also, we need to establish a human colony elsewhere to ensure the survival of our species should a major disaster occur, like an asteroid hitting the earth.

For the rest of this winter right into spring, you can also look for a comet in Perseus. Comet PanSTARRS (C/2017 T2) was discovered by the PanSTARRS 1 telescope in Hawaii on Oct. 2, 2017. It is now in Perseus just 1 degree above the famous double cluster in Perseus. At magnitude 9.5, you’ll need a small telescope to see it. It will brighten 8.8 magnitude by the end of the month and will continue to brighten until it reaches perihelion nearest the sun on May 4. It may reach fifth magnitude by then and become visible without any optical aid.

You have probably already heard that Betelgeuse, the red supergiant star in Orion and in the middle of the Winter Hexagon, is now at its dimmest in recorded history at 1.5 magnitude. Betelgeuse is already a variable star and will probably get brighter again. What makes the situation more dramatic, though, is that in the middle of last month, the LIGO and VIRGO detectors detected a burst of gravitational waves from that area of the sky. That doesn’t mean that Betelgeuse is about to blow up as a supernova, but it does make the whole story far more interesting. The detection hasn’t been confirmed and it was not followed up with a burst of neutrinos, so it was probably just a coincidence. Keep your eye on this star and if nothing else, photograph it to see how much dimmer it will get.

FEBRUARY HIGHLIGHTS

Feb. 1: First quarter moon is at 8:43 p.m. EST.

Feb. 4: Astronomer Clyde Tombaugh was born on this day in 1906. He would discover Pluto just 24 years later on Feb. 18, 1930.

Feb. 8: French writer Jules Verne was born in 1828.

Feb.9: Full moon – also known as the Snow, Hunger, or Storm Moon – is at 2:34 a.m.

Feb. 10: Mercury reaches greatest eastern elongation from the sun this evening and is visible just below Venus.

Feb. 15: Galileo was born on this day in 1564. Last quarter moon is at 5:18 p.m.

Feb. 18: The waning crescent moon will occult Mars right after sunrise.

Feb.19: Nicholas Copernicus was born on this day in 1473. The moon will pass near Jupiter this morning.

Feb. 20: The moon will pass near Saturn this morning. John Glenn became the first American to go into orbit on this day in 1962. The Russian Yuri Gagarin beat him to it on April 12 of 1961.

Feb. 23: New moon is at 10:33 a.m. Ian Shelton discovered Supernova 1987A on this day in 1987 in the Tarantula nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Pioneer 11 left our solar system on this day in 1990.

Feb. 27: The waxing crescent moon will pass within 5 degrees of Venus this evening after sunset.

Bernie Reim lives in Wells and is co-director of the Astronomical Society of Northern New England.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story