Fifth in a series

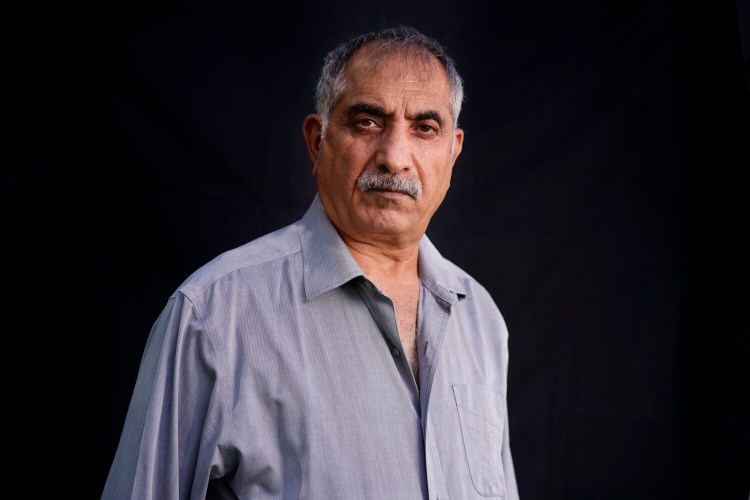

In the days and months following the Sept. 11 attacks, Yasin Ahmady was verbally and physically attacked several times by people who thought he looked like a terrorist.

They were soul-crushing experiences for a man who had come to Maine from Afghanistan 20 years before and now was a U.S. citizen who viewed this country as his beloved home. Ahmady was among many Muslim Americans and others who suffered similar attacks in Maine and across the nation, but it didn’t stop him from spending much of the next decade assisting U.S. forces in his native country.

“It felt bad,” Ahmady, 65, recalled last week. “I was just doing my job. They didn’t know me or what I would do for this country.”

At the time of the Sept. 11 attacks, Ahmady was a parking officer for the city of Portland – a job that doesn’t have a broad fan base under the best circumstances. He wrote out parking tickets. He attached wheel locks, or booted cars, when tickets went unpaid. Still, it was a respectable job and steady work for a man who came of age fighting the Soviets in the mountains of Afghanistan.

For some Americans, the change in attitude toward people like Ahmady was immediate. One man threatened him on the day of the attacks, before Ahmady even knew they had occurred.

Ahmady was on Woodmont Street, near the University of Southern Maine, checking on a complaint about an illegally parked car. The man came out of his house waving a handgun and calling him a terrorist.

“Leave here or I will kill you now,” the man shouted.

Ahmady radioed the parking dispatcher and police came to investigate. The man denied making the threat. Ahmady didn’t press charges. He spoke publicly about the incident the next day, when nearly 500 people gathered on the steps of City Hall to show support for Portland’s Muslim community.

Ahmady did bring charges in two other incidents. One occurred on Congress Street on Sept. 21, 2001, when a Portland man shouted obscenities and ethnic slurs after Ahmady placed a parking ticket on his windshield. The man slapped the ticket against Ahmady’s chest, pushed him backward and tried to spit on him, according to the complaint.

The other incident happened on Feb. 28, 2002, when Ahmady was locking a wheel on a Rockland woman’s car because she had failed to pay parking tickets. The woman kicked Ahmady in the foot, spat in his face and shouted, “Go back to the country you came from. You don’t belong here,” according to a Press Herald report.

In both cases, the state Attorney General’s Office won court injunctions under Maine’s Civil Rights Act. Both assailants were banned from having contact with Ahmady, or from using or threatening to use physical force or violence against anyone because of their national origin.

At the time, Assistant Attorney General Thom Harnett said that since the Sept. 11 attacks, his office had seen a spike in assaults and threats against people who were Muslim or perceived to be Muslim. Across the United States, the number of reported hate crimes against Muslims jumped from 28 in 2000 to 481 in 2001, and they have exceeded 100 per year ever since, according to FBI statistics.

Later in 2002, Ahmady became an interpreter for the U.S. military in Afghanistan, leaving behind his first wife, from whom he was separated, and his four children. It was a major accomplishment for Ahmady, who spoke no English when he came to Maine in 1982. But he took classes as soon as he got here and learned fast.

Plus, he had many years of experience working as an interpreter and cultural liaison for Maine Medical Center, Mercy Hospital, the Portland Police Department, Catholic Charities Maine and various state agencies. He had even applied for jobs with the CIA and FBI before the Sept. 11 attacks, but they told him then that he didn’t have the skills they needed.

“I appreciated what this country had given me and I wanted to give back,” Ahmady said. “I was a freedom fighter before I come to this country, so I know what to do. I wanted to help my family and other people in Afghanistan. Everyone was living in fear of the Taliban.”

Working out of Bagram Air Base from 2002 to 2011, Ahmady went on military missions three to four times a week and narrowly escaped death several times. He points to scars on his legs and explains how he lost 16 teeth in one attack.

He proudly displays medals he received for his contributions to the war effort, including a Purple Heart inscribed with his name and dated May 29, 2004. Although he wasn’t an official member of the U.S. military, the soldiers he worked with made sure his contributions were recognized.

Ahmady doesn’t like to share details of his nine years with U.S. troops, but he said he carried a gun 24-7 and did what he had to do to survive and protect the soldiers he worked with. He pulls up photo after photo on his cellphone and rattles off the names of former comrades in arms. Men he still considers friends. He has stayed in touch with some. Four died in one attack in which he was the sole survivor.

“I will never forget those guys,” Ahmady said. “I fight alongside them second by second.”

Ahmady returned to Maine in 2011 a shell of the man he once was. Diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, he attempted suicide and was hospitalized several times, he said. His relationships suffered and he became addicted to prescription medications that did nothing to curb his anxiety and depression, he said.

In recent years, Ahmady stopped taking medications and is treating his PTSD with regular counseling and by staying active and involved in his community, he said. He tries to be a good man and a good Muslim. He is happily married to his third wife and enjoys seeing the success of his four children. One is a vice president in a financial firm. The youngest is in college.

His greatest disappointment lately has been the way United States ended its war in Afghanistan. He fears that whatever was accomplished during the last 20 years will be lost. He hopes world leaders will hold the Taliban accountable, ensure the safe departure of Afghans who want to leave, and protect women and children who are left behind.

“It’s not easy for me to see what is happening in Afghanistan today,” Ahmady said. “I went back for nine years. I lost a lot of colleagues there. Now, my family is in danger. The people of Afghanistan are in danger. I don’t know if they can have a good life again. I just hope for peace.”

Coming tomorrow: A teacher who learned about caring for students

Read Sunday’s profile: Ticket agent struggles with guilt, trauma over two decades

Read Monday’s profile: Watching 9/11 attacks from classroom sparked social activism

Read Tuesday’s profile: Soldier from Portland knew that 9/11 attacks would change his life

Read Wednesday’s profile: For sisters of Mainer on doomed flight, ‘It’s the day our family changed forever’

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.