REGION — In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s many local towns were licensed to spread sewage sludge (solids) or septage (liquids) on agricultural fields in Franklin County. What that practice may mean in the future should tests reveal high levels of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, (PFAS or forever chemicals), is unknown.

The Town of Farmington, the Farmington Wastewater Treatment Plant, and Wilton Sewer District had licenses to spread solid sewage on almost 340 acres in Farmington, Wilton, Chesterville and Phillips. Most of the licenses were for five years, with some being renewed for another five years. Materials may not have been spread at some sites even though there was a license to do so.

Several towns in northern Franklin County had licenses to spread liquid sewage on farms or town-owned land. International Paper Timberlands had a three-year license to spread pulp and paper mill sludge on 776 acres in Jim Pond TWP.

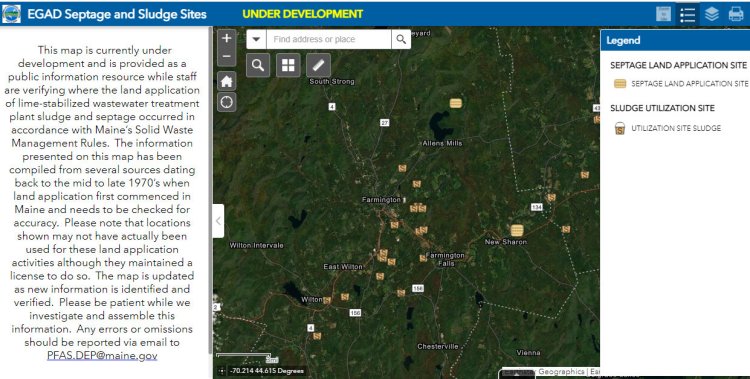

Several locations in northern Franklin County, seen on this map, were licensed to spread solid or liquid sewage waste on decades ago. Wastes may or may not have been spread at a particular site. Screen capture

Some of the farms where sewage waste was spread are no longer in business, have been sold, or have new owners. Records on how much was spread annually or for how many years may no longer be available.

Attempts to reach farmers were not successful in many cases. Others did not wish to provide information. One of those farmers did say mill sludge could be more of an issue than municipal waste.

“There was competition for it,” Wilton farmer and Sen. Russell Black said last week. He said he was leasing farmland from Richard Corey and spread sludge on land near the current transfer station for two or three years.

“The town spread it in other places besides there,” he said.

With forever chemical risk identified throughout the state, Black was uncertain what those prior practices would mean for local farmers, the land where sludge was once spread.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Can you use it for mulch hay, spread it? Can you grow Christmas trees on it? What’s going to happen between solar and PFAS?”

When wastewater sludge was spread in Wilton, Rhonda Irish was not Town Manager. Last week she said she was not aware of that.

“That was before the new treatment plant was built,” she said.

It will take years for the Maine Department of Environmental Protection to work through the ever-changing list of more than 700 properties that had been licensed for sludge dispersal. The agency has prioritized the list based on the type and amount of sludge spread at the site and its proximity to housing.

Forever chemicals are found in most industrial settings. Some sources are waterproof jackets and fast food wrappers.

On Monday, Feb. 7, the Legislature’s Environmental and Natural Resources Committee voted 10-3 to support an amended bill that would stipulate sludge could not be spread on land or used in composting unless it tested under the state’s screening levels for multiple types of PFAS compounds. One amendment isn’t written yet but added a fund administered by DEP to assist towns with additional costs of shifting from spreading sludge or compost to landfilling.

Only four towns in the state still spread sludge while a few others spread compost, Sharon Treat with the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, wrote in an email Tuesday, Feb. 8. There was bipartisan support for the bill which will take weeks to go through the House and Senate, she said.

“With the DEP fund added, that means a fiscal note so after initial floor votes the bill gets tabled with every other bill that has a financial cost/appropriation and those all get the final vote at the very end of the session (unless the Appropriations Committee decides to move it ahead early by exempting it from the “table” which is unusual, but does happen),” she wrote. If enacted, the bill would go into effect upon the Governor’s signature or 90 days later if the emergency preamble does not stay on the bill, she noted.

“Nothing is stopping these towns from starting to landfill right away,” Treat wrote. “As was reported to the committee, once DEP required wastewater treatment facilities to test sludge for PFAS several years ago, it was found everywhere, and quite a few facilities/towns decided then and there to shift to landfill disposal.”

Farmington sewage is being sent to the Hawk Ridge facility in Unity to compost/landfill, Wastewater/Sewer Department Head Stephen Millett said Tuesday, Feb. 8.

“I don’t know where they expect us to put it,” he said. “We don’t generate it, it’s what we get. We’re getting blamed for it.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.