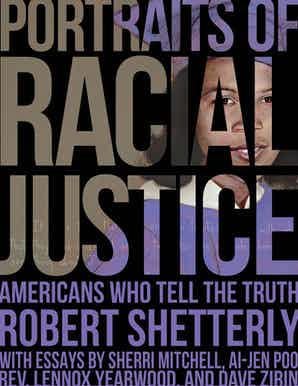

Robert Shetterly wants to recognize Americans who “told truth to power” and has done so in a beautifully crafted book that includes his paintings of 50 leaders in the struggle for racial justice, quotations from each of the portrait subjects, and essays by four of them.

The resident of the Down East town of Brooksville describes “Portraits of Racial Justice: Americans Who Tell the Truth” as “at its core an art project.” Shetterly began painting portraits of social justice leaders in 2002, after the U.S. invasion of Iraq. He wanted to “exorcise the shameful liars who were colonizing my head and heart and replace them with portraits of Americans who made me feel proud of this country.”

Although only 118 pages long, “Portraits of Racial Justice” is a remarkably powerful success, achieving its lofty ambitions of being “an art book, a history book, a guidebook, a curriculum and a manifesto.”

Shetterly’s paintings seek both to honor the portrait subjects and to convey something essential about them. His portraits are at once personal and emotive, conveying a mixture of tenacity, hope, grace and, in some cases, impatience verging on anger. The subjects’ eyes that look out directly at the reader are especially expressive and consistently among the most engaging aspects of the portraits. They establish a sense of personal connection with the reader.

The overall impact of the portraits is enhanced by quotations from the portrait subjects who speak for themselves – and by brief biographical sketches contextualizing their contributions to racial justice. Shetterly calls the synergistic result “a community” of Americans who are “unafraid to name the failures of this country and the injustices of power that benefit from those failures.”

While some of Shetterly’s portrait subjects are still living, many of them are well-known historical figures, such as Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Harriet Tubman and James Baldwin. Shetterly also recognizes lesser-known people who have made important contributions to racial justice.

For example, before Rosa Parks famously refused to sit at the back of the bus in 1956, Ida B. Wells declined to move to a segregated part of a train in 1883, and had to be moved there by the conductor; Pauli Murray and 15 others were arrested in 1940 for refusing to give up their seats on a bus in Petersburg, Virginia; and in 1955, Claudette Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to white passengers.

There are portraits highlighting the racial justice contributions of a wide range of other people as well: Tarana Burke, the nonprofit executive who empowers survivors of sexual violence; Bryan Stevenson, who represents people incarcerated on death row; Carlos Muñoz, a pioneer in the Chicano studies movement in higher education; Barbara Johns, whose protests at her high school led to litigation that became part of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case; and Bree Newsome, whose performance art included climbing a flagpole and taking down a confederate flag at the South Carolina state capitol.

Maine racial justice advocates are well represented in the book.

Denise Altvatar is a co-founder of the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission that seeks to acknowledge the horrific “foster care nightmare” that happened to Wabanaki children in the Maine Child Welfare System, of which Altvatar is a survivor. The commission seeks to help heal survivors and to create the best possible system for Wabanaki children and their families.

Deqa Dhalac, currently serving as mayor of South Portland, is a community organizer who says, “as a Black, migrant, Muslim woman,” she wants to be “a force for positive change,” in creating communities “where everyone feels welcomed and included.”

Sherri Mitchell Weh’na Ha’mu Kwasset, who was raised in the Wabanaki Confederacy within the borders of the state of Maine, is an Indigenous rights lawyer, author and founding director of the Land and Peace Foundation, which focuses on protection of Indigenous rights and preserving the Indigenous way of life.

Maulian Dana, who serves as Penobscot Nation Tribal Ambassador, became engaged with activism in high school when she protested stereotyping of Native Americans as mascots. With her poetry and by leading legislative changes, she “is transforming the perception of Native peoples” in Maine.

Portraits of Racial Justice is part of an ongoing effort founded by Shetterly that now includes a nonprofit organization called Americans Who Tell The Truth. Its mission is using “the power of art to illuminate the ongoing struggle to realize America’s democratic ideals and model the commitment to act for the common good.”

Rev. Lennox Yearwood Jr., a portrait subject and essayist in the book, best captures Shetterly’s message: “100 years from now none of us will be here. But what will be here is the spirit of us fighting for a just, sustainable prosperous world for all. We fight not only for ourselves but for future generations.”

Dave Canarie is an attorney and adjunct faculty member at University of Southern Maine who lives in South Portland.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.