Is there something in the drinking water in Bridgton, Maine?

Tom Johnson, former director of the Rufus Porter Museum of Art and Ingenuity and a member of its advisory board, thinks so.

“We have a lot of really talented artisans up here that follow directly in the footsteps of Porter,” Johnson said. “Really something up here inspired them.”

Porter, also a scientist, inventor and journalist who was once dubbed “The Yankee Da Vinci,” was best known for the wall murals he painted, and inspired, throughout New England.

The museum at 121 Main St. shows Porter’s creativity. On June 20, with the opening to the public of the new Graham Center, visitors will see how he influenced others too — in this case, his nephew, Jonathan D. Poor of East Baldwin, whose Norton House murals will be on display.

It was Johnson who discovered Porter’s Church House murals during a family vacation in 1985. Following a rumor, Johnson went to an abandoned mill worker’s house that was about to be burned by the local fire department for practice. After pulling away some of the wallpaper, Johnson discovered some of Porter’s forgotten work.

Porter was born in West Boxford, Massachusetts, and his family moved to Maine when Rufus was 9 years old. He spent his formative years in Pleasant Mountain Gore in Denmark and attended Fryeburg Academy for six months.

“His roots trace through this part of western Maine, but also through Portland and all throughout New England,” museum Executive Director Dan Dinsmore said. “I think that his ability to kind of reinvent himself and to make his way during early America — I think he epitomizes the American spirit and that early American pioneering way of just trying to figure out how to get things done.”

The museum showcases the artist’s silhouettes and murals, including those of the Church House murals.

The Graham Center will feature the Norton House murals painted by Poor, who was inspired by Porter’s distinct flair for New England landscapes.

It was not an easy task to display the murals, which had to be dismantled, moved and installed by museum preservation contractor David Ottinger. Instead of removing the plaster layer, Ottinger removes the entire wall. Although a major process that requires transferring structural support onto horizontal braces, this allows for the delicate plaster to be supported throughout the entire process.

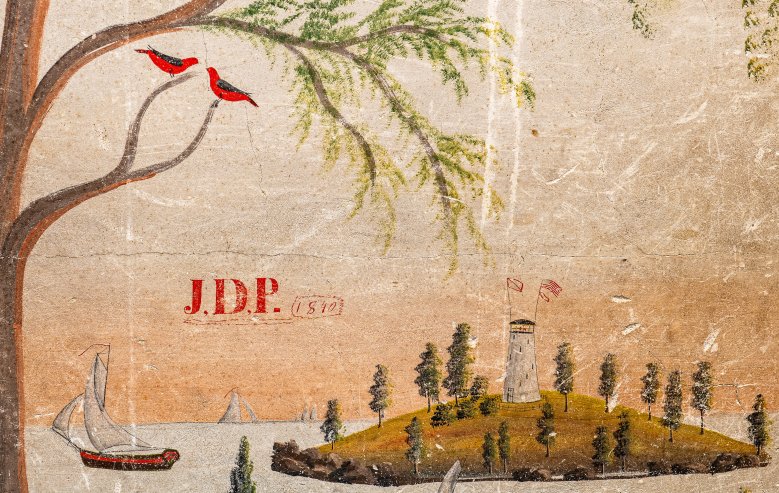

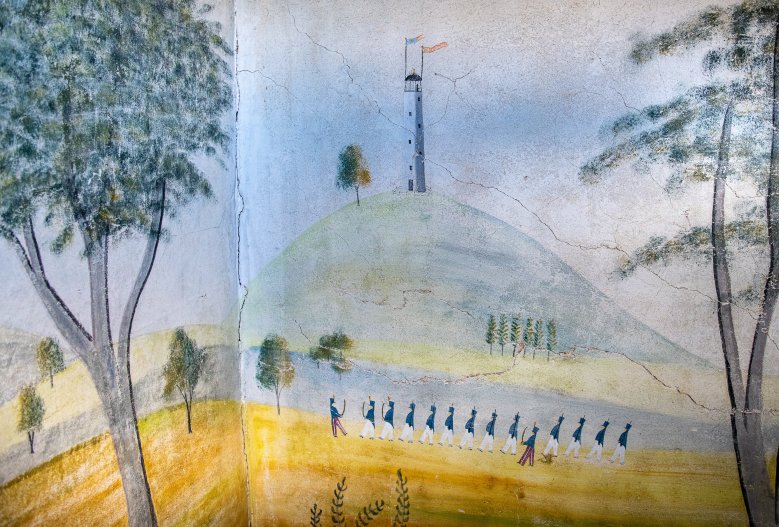

Like Porter, Poor’s Norton House murals feature sprawling New England scenery, alternating between broad, blurred brush strokes of land and sky and precise stenciled figures. The murals sport Porter’s signature blue, green, red and umber color scheme.

At first glance, the walls create an idealized landscape, but it is Poor’s details that make the murals come to life. The Norton Hotel has an 1840 sign in homage to the mural’s patron; shrubs can be identified as sumac, and landmarks like Casco Bay and the Portland Observatory are all included. In this jumbled portrait of real and imagined New England, Poor features everyday life. The mundane takes center stage with snapshots of clotheslines and piles of manure.

Ottinger calls it a “unique and unrecognized form of American art.”

Ottinger, who has been dismantling and assembling wall murals for 43 years, oversaw the murals’ installation in the Graham Center. “These are local scenes and they’re local artists’ interpretations,” he said, pointing out that the paintings are not derived from European precedents. “It really communicates a lot about what the people in the 1830s and ’40s were thinking and their comfort with their world.”

Vine-like vegetation borders many of the murals, meandering along the landscapes. The rooms within the Graham Center are furnished with items contemporary with Poor’s time. “I think it’s really interesting to not only look at the walls, but also see how people, how James Norton and his wife, Lydia, and their two kids, would have lived with these murals,” museum acting curator Lucas Gillespie said.

Gillespie, a Hobart and William Smith College graduate, describes the museum’s intrigue, admitting that he “had no idea who Rufus Porter even was at this time last year.” Bound for a Cooperstown graduate program, Gillespie said the museum has “really become a big part of my life.”

The museum has grown over the years due to volunteers and donations from local businesses and private patrons. Diane Barth, a museum trustee, described the museum as a community effort centered around a local celebrity.

“Without the acceptance of a community, a museum never goes far,” Johnson said. “You’ll always have support from outside your community, but it’s the community insiders that make things like this possible.”

Whether it is a fascination of Porter and a desire to preserve his oft-forgotten legacy, a passion for American Folk Art or a rallying point for the community, the Rufus Porter museum has become a “cultural enclave” for Bridgton, Johnson said.

Much like Porter’s and Poor’s landscapes, it’s in the details. What may seem like a typical small inland Maine town includes a wealth of Porter history and art.

“It means a lot,” Johnson said about the museum’s place in Bridgton. “It’s a cultural anchor for the downtown.”

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.