SKOWHEGAN — Donnie Zaluski sees his job as crucial to the functioning of society.

“We clean the water,” said the superintendent of the Skowhegan Water Pollution Control Plant.

But as one of the oldest wastewater treatment plants in the state, Skowhegan’s facility, along with its sewer system, are constantly in need of improvement. So with the select board’s approval in August, a facility master plan study is now underway.

The planned plant improvements follow more than two decades and millions of dollars’ worth of investments in improving the town’s sewer system. The understanding of wastewater treatment and the biological processes that underpin it, meanwhile, continue to advance, Zaluski said.

And, Zaluski said, improving the plant goes hand-in-hand with ongoing efforts to revitalize the region’s economy and embrace Skowhegan’s connection to the Kennebec River.

“It’s a really good opportunity to optimize the plant and set it up for the next 20 years,” Zaluski said during a recent tour of the town’s plant, off Joyce Street.

Zaluski, 40, of Turner, was hired this spring as the water pollution control superintendent after longtime superintendent Brent Dickey retired. Before Skowhegan, Zaluski worked for the Portland Water District and did offshore work in Alaska.

Zaluski, though, is no stranger to the region: he grew up in the area and went to high school in Madison (and his mother is a recently retired employee of the Maine Trust for Local News and its predecessors).

“I’m excited to be here,” Zaluski said. “I want to acknowledge Brent for doing such a good job for 37 years. We have a precedent of really good environmentalism in this town. We can take that and keep that momentum going. We can do some really cool things for the community with an upgrade — things that bring budgets down.”

The plant at 53 Joyce St. takes sewage and stormwater from approximately 36 miles of collection system, treats it and discharges the cleaned water into the Kennebec River.

The facility, operated by four workers and staffed 365 days a year to meet state and federal permitting and data reporting requirements, is rated to take up to 1.65 million gallons a day.

The treatment process used in Skowhegan is fairly standard, Zaluski said. It largely uses aeration to feed bacteria, which naturally break down nutrients. The final step before water is put into the river is disinfection, done with sodium hypochlorite, commonly known as bleach.

Most of the municipal sewer system is downtown and in the surrounding neighborhoods, although parts of it extend outward, including underneath portions of Madison Avenue, North Avenue, Malbons Mills Road, Norridgewock Avenue, Waterville Road and Middle Road.

A 2019 study reported 5,000 people using the sewer system across 1,500 connections. The system is funded by town property taxes, rather than ratepayers like in a quasi-municipal district.

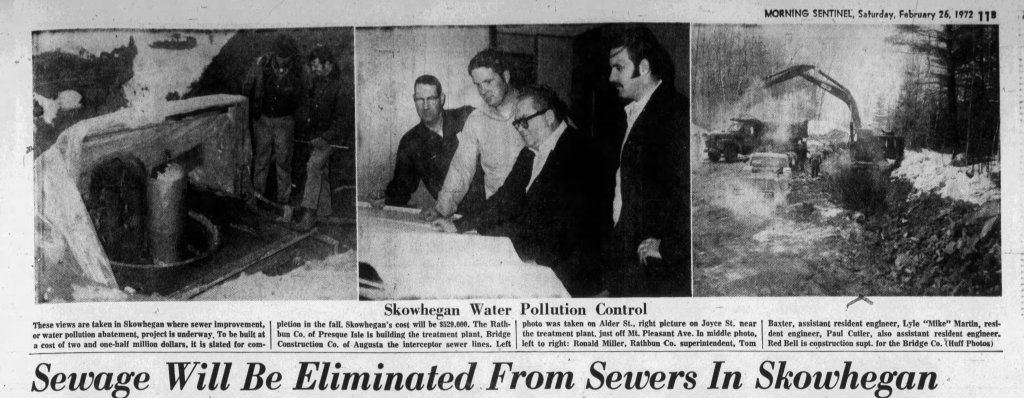

Skowhegan’s treatment plant dates back more than five decades. Newspaper archives show town voters approved funding in 1971. The plant was built mostly in 1972 and opened the next year.

Zaluski points out the Clean Water Act — the federal law regulating what can be discharged into bodies of water — was enacted in 1972, indicating Skowhegan’s leaders at the time were thinking ahead. The law prompted many communities across the country to build their wastewater treatment plants.

“This town has helped shape the health of that river and they’ve done that in a proactive manner.”

Donnie Zaluski

The last major upgrade of the treatment plant was in 2004, with smaller improvements done about 10 years later, according to records Zaluski compiled.

The town’s investment in the last 25 years has focused less on the plant, but more on reducing the impact of its combined sewer overflow.

Like in many older communities, especially those in the Northeast, Skowhegan’s system was designed to carry stormwater and wastewater in the same pipes.

Under normal conditions, all of it goes to the pollution control plant. But during heavy rainfall or snowmelt, the volume of water exceeds the system’s capacity, and and the system discharges untreated water.

Approximately 700 communities in the U.S. have combined sewer systems, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Efforts have been underway in those communities to separate the systems so that stormwater doesn’t flow into the plants, burden the systems, and cause untreated discharges.

As of 2024, Maine had 32 combined sewer overflow permittees in 29 communities, according to the most recent annual report from the state Department of Environmental Protection. Fifteen systems in Maine have fully completed their abatement plans, which the DEP began requiring in the early 1990s in response to federal requirements.

Mitigation work in Skowhegan has been done in phases funded by three bonds. The ultimate solution, Zaluski said, is separating stormwater and wastewater into different pipes throughout much of the system. But that essentially requires digging up every street.

The town has spent more than $20 million on the improvements. The work has resulted in an approximately 80% reduction in untreated discharges since the early 2000s, Zaluski said, although DEP data shows discharges vary widely by year.

For example, the system reported untreated discharges of approximately 253,000 gallons in 2021, 1.7 million gallons in 2022, 7.9 million gallons in 2023 and 2.4 million gallons in 2024, according to the DEP’s 2024 annual report. The number of discharge events has decreased steadily, with six reported in 2024.

With abatement work ongoing — the town has to file an updated master plan with the DEP every five years — Zaluski is now focusing on the plant itself.

The select board approved spending $42,500 for a facilities plan study; the town hired Olver Associates of Winterport to conduct it.

The six-month study is expected to continue into 2026. The goal is to go through every single asset and determine what to keep, what to get rid of, and what to improve. When complete, there will be proposals at a town meeting, when voters can decide if they want to proceed and what projects they want to fund.

Zaluski said improvements would likely include repairs to tanks and opportunities to use new biological technology, such as anoxic and anaerobic treatment zones in addition to the current aerobic treatment. Preventative maintenance is cheaper than major emergency repairs, he said.

He is also looking at ways to keep costs down. Aside from personnel, the department’s top cost in its roughly $1 million annual operating budget is disposal of sludge. The state has required sludge, which had been spread on farmland, to be taken to landfills because of the potentially harmful impacts of so-called forever chemicals known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS.

Zaluski said odor control measures could be considered as part of the ongoing facility study. In some cases, he said, the solution could be as simple and inexpensive as adding covers to tanks that are currently exposed. More advanced technology is available, too.

Some have pointed out that the plant’s location is less than ideal, just downstream of multimillion-dollar plans to build the long-discussed whitewater River Park, associated trail projects and riverfront improvements. Dealing with sewage comes with an odor.

“Odor control is tough because it’s sort of an elective,” Zaluski said. “It’s a public perception thing. It doesn’t improve the quality of your effluent, but it improves your public image.”

The planned improvements would also set the plant up to accommodate economic growth, Zaluski said.

He is working to develop an ordinance around an industrial pretreatment program, to put a formal framework in place for large, commercial users such as Gifford’s Ice Cream, as well as others that want to move to town.

“I’m looking at resilience in the capacity that we have,” Zaluski said. “It’s an economic driver. If a new business comes in here, we need to be able to handle it.”

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can update your screen name on the member's center.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.