A week after The Nature Conservancy announced it plans to purchase and remove four Kennebec River dams owned by Brookfield Renewable Energy, initial fears about flooding, immediate layoffs, recreation and environmental harm have subsided.

But some questions remain. Here’s what we’ve learned about the impacts of one of the largest river restoration efforts in the country.

Job security and mill operations

Justin Shaw faced some tough questions last week.

Like the 500 members of United Steelworkers 4-9, the largest union at Sappi’s Somerset Mill in Skowhegan, Shaw found out last Tuesday about The Nature Conservancy’s plan to eventually remove the four dams — a move that places the future of the mill in doubt. Mill leaders had been bound from informing workers under a non-disclosure agreement, Shaw, the union’s president, said.

The union members rallied last year for protections against excessive forced overtime, changes to health insurance and vacation time reductions. But now, with the potential removal of the Shawmut dam in Fairfield, which Sappi officials have said is necessary for mill operations, Shaw said many of his members are more concerned about the security of their jobs and their livelihoods.

“I’ve got members asking: ‘Do I need to dust off my resumé?'” Shaw said.

Not immediately, it appears.

Like the workers in their mill, Sappi officials were also “concerned” about the future of the Shawmut dam impoundment.

In a statement issued just over an hour after The Nature Conservancy’s announcement, company leaders said dam “removal would jeopardize the viability of the Somerset Mill and the thousands of Maine jobs connected to Sappi’s operations.” Republican leaders also jumped at the chance to criticize Gov. Janet Mills, a Democrat, for what they called a “hollow” promise in 2021 to keep the mill open.

In the week since, though, temperatures have cooled.

Shaw, for one, is hopeful about a deal.

The Nature Conservancy — which hopes to remove the four dams to restore sea-run fish passage— has repeatedly expressed its commitment to finding a solution that keeps the mill open. The conservation organization also has a stake in the forestry products industry, being one of the state’s largest forest landowners and using paper manufactured at the mill to print 3 million copies of its magazine each year.

“I’m optimistic that we can find a compromise,” Shaw said. “(The Nature Conservancy seems) willing to work with Sappi. They don’t seem like they want to put people out of jobs or a business out of business. So, I’m optimistic.”

Shawmut dam relicensing continues

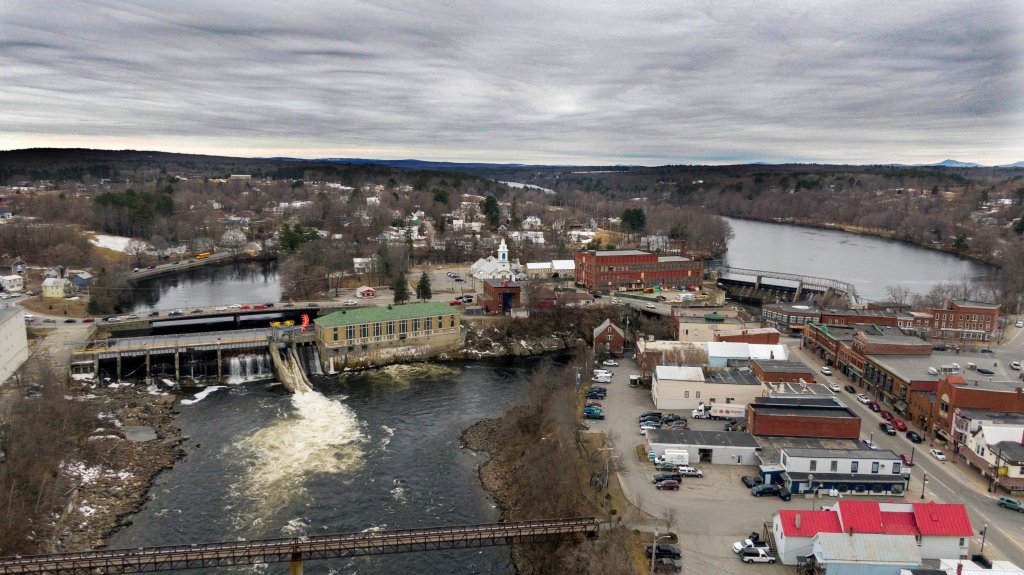

Brookfield Renewable Energy, the owner of the four dams, is in the process of relicensing the Shawmut dam in Fairfield. Approval would allow Brookfield to continue generating about 8.65 megawatts of hydroelectric power at the site.

While The Nature Conservancy said Brookfield planned to continue operating the dams until the sale is complete, it was not immediately clear if the sale would affect the pending water-quality permit under review by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection.

After federal approval earlier this year, the state permit remains the final piece of the relicensing puzzle for the Shawmut dam.

DEP Deputy Commissioner David Madore confirmed Thursday that the sale should not have any impact on the pending permit application, which is expected to be decided by Oct. 20.

A Brookfield spokesperson did not respond to questions about the company’s continued interest in the license.

No changes to river flow, Skowhegan River Park

At the end of what it expects to be a decadelong process, The Nature Conservancy hopes to remove the four dams. For many who live and work along the Kennebec River, that has raised questions about worsened flooding and other hydrological impacts of dam removal.

But it’s unlikely that these four dams being removed would have a serious impact on floods, experts say.

The dams are run-of-river dams — or dams that use the natural flow of the river to generate electricity.

“If you look at other parts of the country, they have large reservoirs that are kept empty, and their purpose is to catch and hold water during a major flood,” said Nick Stasulis, a supervisory physical scientist for the U.S. Geological Survey in New England. “These are not that. At higher flows, these dams don’t have the ability to hold back huge volumes of water. Maybe at the initial part of the peak — but, you know, once we’re at a high-flow condition, they don’t have the capacity to hold that water back.”

Engineers working on the Skowhegan River Park — a new multimillion dollar recreation area that includes artificial whitewater rafting and river surfing on the Kennebec River just below the Weston Dam — came to a similar conclusion.

“This section of the river is primarily controlled by downstream conditions, meaning the presence or absence of Weston Dam does not substantially alter flow characteristics within the River Park footprint,” Main Street Skowhegan officials said in a statement last week, citing hired engineers. “Additionally, Weston operates in a ‘run of river’ mode, which means it does not store or regulate water flows in a way that would influence the Park’s hydrology or design.”

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.