Gordon Parks arrived in Maine in January 1944 on the heels of a walloping snowstorm.

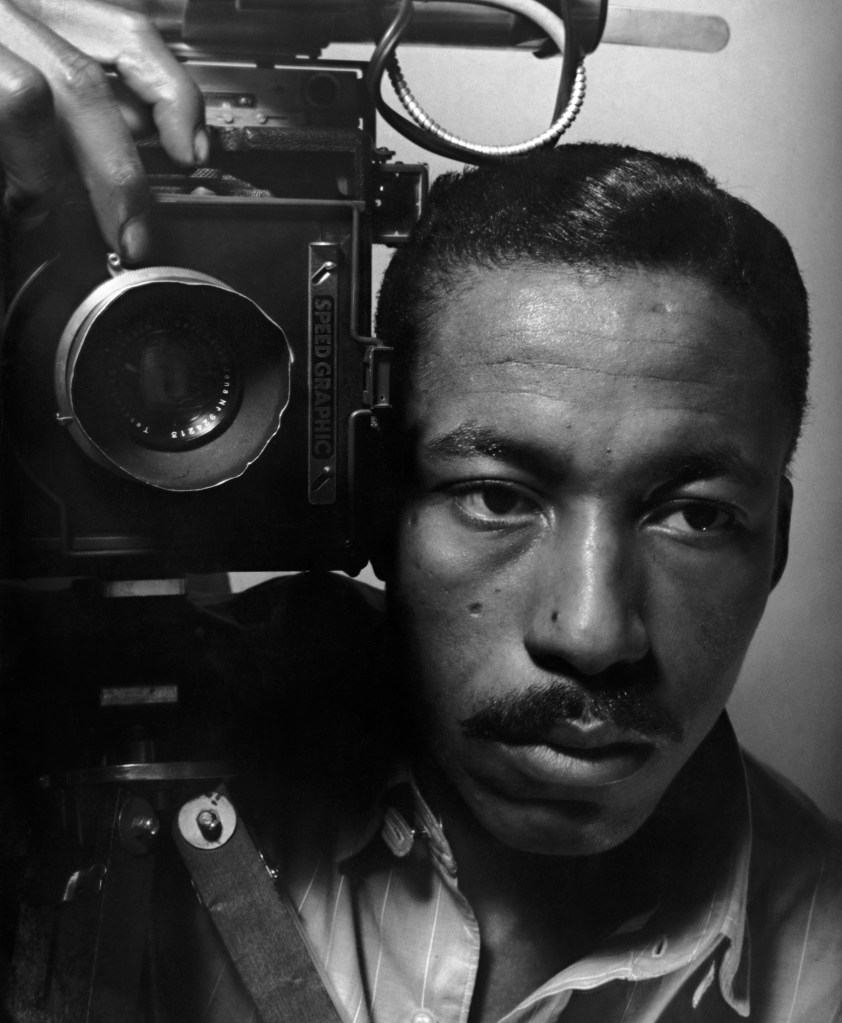

The photographer would become a household name as he spent six decades documenting American life and culture in the 20th century. He made images of the most famous people of the era and captured the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s. He was the first Black staff photographer at Life magazine.

But before that, Parks photographed the general store and Esso gas station in Somerville on assignment for Standard Oil Company. He also took pictures of a lobster bake in Augusta, Navy pilots at a flying school in Portland, a farmer and a family at their dinner table. His images offer a glimpse into his early career and into life in Maine during World War II.

Now, 65 photographs from that assignment are on view for the first time at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art until Nov. 9.

“He was still young in his career and trying to form who he was and how he would take pictures,” said Peter W. Kunhardt Jr., executive director of the Gordon Parks Foundation. “These early pictures of Maine are clear examples of his ability to take a good photograph.”

Frank Goodyear, co-director at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, first contacted the Gordon Parks Foundation because he felt the collection was missing work by this noted photojournalist. He didn’t know Parks had ever set foot in the state until Kunhardt said, “Would you be interested in any of Gordon’s works that he made in Maine?”

“They’ve never really been shown,” Goodyear said.

TRAVELING TO MAINE

During World War II, Standard Oil did not fare well in the court of public opinion. The company faced allegations of price gouging and collusion with a German chemical company.

“Executives from the company get hauled before Congress and really chastised publicly for these bad decisions,” Goodyear said. “And one response by the company was to form this photographic project that would provide images that help to tell the story of oil and gas, how it made the lives of Americans better and how Standard Oil was contributing to the larger war effort at the time.”

Parks had previously worked for the Farm Service Administration. (It was there that he met Ella Watson, who cleaned government offices and was the subject of one of his most famous images, titled “American Gothic.”) His former boss was leading the PR project at Standard Oil and hired Parks. Photographers fanned the country to document everything from the people who operated local gas stations to the farmers who relied on oil for their machinery.

So Parks went to Maine.

One challenge might have been fear about an attack on the state during World War II, which led to restrictions on cameras along the coast.

“The photographic record of Maine during World War II is remarkably thin, in part because there were prohibitions that the Defense Department put in place,” Goodyear said.

Another was certainly his safety. Few records or letters exist about his time here. History tells us that traveling alone as a Black man in a predominantly white state would have been dangerous in 1944. The Green Book, a guide for Black travelers published from 1936 to 1967, might have offered some guidance on some places to stay and eat in Maine. But Maine is a big state.

“How did he get around?” Goodyear said. “Where did he spend the night? These were open questions. And while we didn’t find receipts for staying here or staying there, evidence in the pictures suggests that, in many instances, he stayed with the families that he was photographing and even ate at the dinner table with these individuals.”

BECOMING GORDON PARKS

One such family was that of Herklas Brown, who operated the Esso gas station in Somerville. He photographed Brown at work and at home and even made a portrait of himself with the family. Parks visited twice — once in January and again in August.

Goodyear sees a difference between the seasons. The winter photographs convey a certain anxiety. The government rationed food and fuel. Two Brown daughters got jobs at a local shoe factory, where many men had left their jobs for war. Parks returned in summer, weeks after D-Day, and photographed a joyful county fair and a gas company picnic.

“There is a sense of hope that the war is coming to an end, and the pictures that Parks makes in Maine in the summer of 1944 are decidedly warmer, not only warmer in the sense that the temperatures are warmer, but warmer in the sense that there is a kind of renewed optimism in the scene and the people,” Goodyear said.

These images also offer a glimpse into the photographer’s ability to build trust with his subjects that made him successful throughout his career. Parks would go on cover everything from racism and poverty to fashion and entertainment. His subjects included Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and Stokely Carmichael. His creative work extended to writing and filmmaking. A trip to this exhibition might lead you to a deeper exploration of the artist’s work, much of which can be found online via the Gordon Parks Foundation.

“The Herklas Brown story is super important to understand how Gordon Parks would become Gordon Parks,” Kunhardt said.

IF YOU GO

WHAT: “Gordon Parks: Herklas Brown and Maine, 1944”

WHERE: Bowdoin College Museum of Art, 9400 College Station, Brunswick

WHEN: Through Nov. 9

HOURS: The museum is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday with extended hours until 8:30 p.m. on Thursdays. On Sunday, the hours are 1-5 p.m. The museum is closed Mondays and national holidays.

HOW MUCH: Free

INFO: For more information about this exhibition, visit bowdoin.edu/art-museum or call 207-725-3275. For more details about Gordon Parks, including a digital archive of his work, visit gordonparksfoundation.org.