Dramatic change is two years away in the region’s municipal waste world, and central Maine communities are facing tough decisions on a tight deadline.

Where to dispose of garbage and how much it will cost is a decision communities across the region have to make soon. A deal to provide above-market-rate electricity between power company Emera Maine and the Penobscot Energy Recovery Co., known as PERC, expires in 2018.

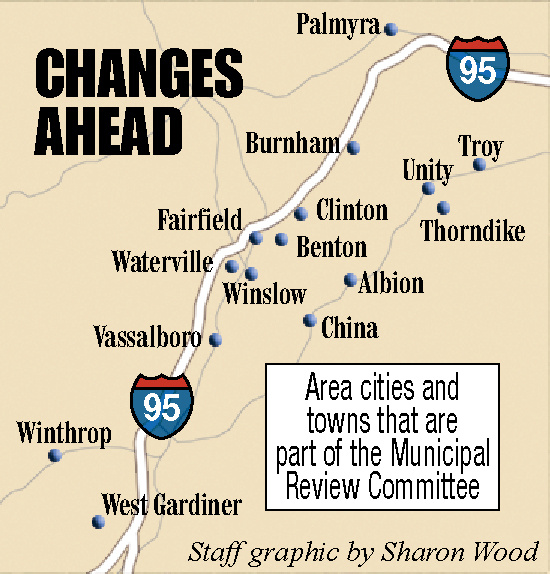

That matters to area communities because it’s also the year long-term waste disposal contracts between PERC and about 180 towns and cities in the state, including more than a dozen in the Waterville and Augusta areas, will end. At stake are hundreds of thousands tons of waste and millions of dollars the communities pay for disposal.

The Municipal Review Committee, or MRC, the organization that represents those communities and owns a quarter of the plant, doesn’t think PERC will be able to survive after the Emera Maine agreement expires.

But PERC maintains that it will be viable after 2018, it has proposed new agreements with member communities, and competitors have offered their own proposals. According to the company, the plant serves more than 300,000 people.

MRC has proposed a new, state-of-the-art plant in Hampden that will produce natural gas derived from trash, and it is asking its members to sign on to 15-year contracts to help develop the plant and provide the material it needs. MRC believes its plan is the most sustainable and economically viable option for member communities.

But some municipal officials, most notably those in Waterville and Fairfield, are skeptical that the technology used by Fiberight, the company that would build the Hampden plant, is workable; and they are reluctant to dive headfirst into an agreement that might go under.

“Frankly, we have looked at PERC for five years and we have real difficulty seeing it survive,” said George Aronson, the MRC’s technical advisor, in a meeting Wednesday with member communities in Waterville.

Fairfield already has decided it is going to let its agreement with PERC lapse and get out of the solid waste business entirely.

That leaves area communities from Waterville to West Gardiner with a decision to make: Where will their share of the 175,000 to 200,000 tons a year that goes to PERC end up? And how much is it going to cost to put it there?

There isn’t much time to make the decision. MRC and Fiberight need commitments by May from enough communities to deliver 150,000 tons of trash annually to the Fiberight plant.

THE WASTE PROPOSAL

In 1991, a few years after it opened, 89 towns and cities sending waste to PERC joined under the Municipal Review Committee to shore up the company’s failing financial position.

Since then, the group has grown to 187 member communities that provide as much as 200,000 tons of trash to PERC annually, the majority of the waste that is processed at the plant.

The MRC started planning for the post-2018 landscape about a decade ago, but the effort kicked into high gear three years ago after the committee decided that PERC would not be viable after its contract with Emera runs out.

In 2013, the MRC solicited proposals for an alternative from a number of companies.

The result is a proposed contract with Fiberight, a Maryland-based company that wants to build a first-in-the-nation waste disposal plant in Hampden that would convert trash into biomethane and possibly other materials.

Recyclables would be sorted out of the trash and organic materials broken down with an anaerobic process to make biofuel. The company has a small-scale test plant in Lawrenceburg, Virgina, but has not built a full-scale plant yet in the U.S.

Under the proposal, MRC would buy the parcel and develop infrastructure, and Fiberight and its financial backers would build and operate the plant.

Last year, Fiberight announced that it had secured an agreement with Covanta Energy corporation, a major waste-to-energy company with 40 plants across the world, to build and operate it.

Under the terms of the deal, municipalities would pay $70 a ton — known as a tipping fee — and would get $5 a ton from revenue generated by the plant. The rate is subject to increase with consumer price increases, but there are no additional pass-through costs, Aronson said.

Members now pay a $76 tipping fee at PERC, but that cost is reduced to $59 a ton after rebates from the company, according to MRC Executive Director Greg Lounder.

Communities in the Fiberight agreement also would agree to keep money in an existing $25 million tipping fee stabilization fund managed by the MRC. From that fund, $5 million would be used to build the utility and road infrastructure at the Hampden site. The MRC would retain ownership of the parcel, while Fiberight-Covanta would own and operate the plant.

Lounder said Friday that to have a major company such as Covanta get on board with the project shows it is viable.

“We independently vetted and validated the Fiberight technology. To have a leading waste energy company like Covanta carry out their due diligence and reach the same conclusion we did is very reassuring,” Lounder said.

Towns and cities would not be required to provide a minimum amount of trash, but the plant does need at least 150,000 tons of waste per year to operate. Under their agreements with PERC, communities have to deliver a guaranteed annual tonnage or be subject to a penalty from the company, although that rule no longer is enforced, according to Aronson.

Towns and cities have until May to sign the contract, although those that have Town Meetings in June can get an extension.

Communities that don’t decide by the deadline can get into the agreement later, but it will cost $2.21 more per ton and they will not share in revenue.

At the meeting of area communities Wednesday in Waterville, Aronson said safeguards had been built into the Fiberight contract to mitigate the risk, including a $3 million account to cover shortfalls.

“We do not want any town to be on the hook for a shortfall,” he said.

NO CONSENSUS YET

While MRC would like all its communities to line up behind its proposal, there is no universal consensus on the plan, and at least one group examining the issue — the Waterville Solid Waste Committee — is skeptical the Fiberight process will work.

The city of Brewer last month became the first MRC community to enter into the Fiberight agreement.

“The City Council has been aware of this issue since 2010. We started talking about 2018 and we had to be prepared for changes,” said Karen Fussell, Brewer’s finance director and an MRC board member.

“As we got closer to this year, it became very clear to them that there was no option to stay with PERC.

“The Brewer council has been getting information all along. They believe in the MRC and that it is looking out for the best interests of its members,” Fussell said, adding that although Fiberight’s technology hasn’t been used in the U.S., it is in place and working in European countries.

Gary Bowman, Oakland’s town manager, said he’s also interested in the Fiberight proposal, but a town committee intends to look at all the options.

“It deserves a good look. This has been working in other parts of the world,” Bowman said. “I certainly think the concept holds a lot of merit, enough so that I’d be willing to push in that direction.”

Oakland is not a formal MRC member, but it sends its waste to PERC through an agreement with Waterville, which takes its garbage to the Oakland transfer station. If it moved forward with a contract, the town intends to become a full member, Bowman said.

“This country was built on risks,” Bowman said. “If you are not looking outside the box, you are not going to get anywhere.”

Towns are going through a fact-finding process and researching the issue in advance of any May votes on a contract.

Ken Fletcher, an MRC board member and Winslow town councilor, said the discussion on which way to go is just starting at the town level.

“I don’t believe anyone has reached a decision or even an inclination, because we want to be as objective as we can and make an informed decision,” said Fletcher, who is also a former Republican state legislator and former energy director for Gov. Paul LePage.

Voters in China will get a chance to weigh in on the matter in March at Town Meeting. One of the warrant articles asks residents whether they will authorize the select board to execute an agreement with MRC and Fiberight.

In Winthrop, town officials are just starting to talk about what the town will do in two years.

“We’re doing a lot of research, and our town manager is meeting with various facilities, and we’re evaluating our options,” said Sarah Fuller, chairwoman of the Winthrop Town Council. “It’s very much on our priority list. We’re hoping to make a decision this year, if all the pieces are in place.”

Other towns may be taking similar action during their annual meetings. But still other communities, particularly Waterville, see it as a nonstarter.

Fred Stubbert, chairman of a Waterville committee looking into the city’s solid waste issues, said Friday that he is “very, very skeptical” that the Fiberight proposal is the right choice financially for the city.

“The concerns are many, financially primarily. The citizens of Waterville need to understand what the options are,” Stubbert said.

Waterville has about $2 million tied up in the MRC stabilization fund that it would get back if it pulled out of the group, he added.

The technology is unproven and hasn’t been scaled up from the test plant, and there will be extensive startup costs, Stubbert said.

The plant doesn’t have an agreement to sell natural gas and is factoring recycling into its revenue model at a time when the market for recyclables has bottomed out, and is planning to fit it out to produce industrial sugars, a material that doesn’t have a market yet, he added.

At the same time, PERC isn’t going to be a viable option, which leaves Waterville with the option of disposing of its trash in a landfill, Stubbert said.

“Unfortunately, that looks like the best alternative right now,” he said.

The Waterville City Council will have a final say on the proposal, but the committee will recommend a path it could take, he added.

“A lot of thinking needs to be done, but the inclination of the committee now is not to work with the MRC,” Stubbert said.

OTHER OPTIONS EXPLORED

Although MRC says PERC is finished after 2018, the company that owns a majority share in the plant says it can keep on going.

In an interview, Robert Knudsen, a vice president for operations at USA Energy, the Minnesota-based company that owns 52 percent of the Orrington plant, said the company intends to alter the plant’s operations and partner with other waste companies to remain viable.

Knudsen disputes the MRC’s assessment that the plant is too big, uses outdated technology and can’t compete after 2018.

“We are actually perfectly sized for the market today,” Knudsen said. “Since we have owned it, we have put $110 million into maintaining it to keep it at peak performance.”

Once the contract with Emera Maine expires, USA Energy will not be obligated to produce a certain amount of energy and can modify its schedule to produce during the times of highest electricity consumption, when prices are higher, a technique Knudsen called “following the load.”

If it doesn’t have to follow its obligations under the Emera contract, PERC could cover its fixed costs with tipping fees and generate revenue with electricity production, Knudsen said.

“In 2018, all those obligations go away; then we are looking at covering our costs and providing a profit,” Knudsen said. “We are not going to operate and produce electricity like we do today,”

The company also has partnered with waste companies Casella Waste Systems; Waste Zero, the company that makes the bags used in pay-as-you-throw municipal waste collection programs; and Exeter Agri-Energy, a Maine company that converts food and farm animal waste into biofuel, to support the operation, Knudsen said.

But the prices PERC quotes are substantially higher than the MRC option.

In a December memo to member communities, PERC quoted an $84.36-per-ton tipping fee for a 15-year agreement or an $89.57-per-ton fee for a 10-year agreement. The company needs to secure about 90,000 annual tons from communities to make its model work, as well as more deliveries from commercial clients, according to Knudsen.

Although the tipping fees are higher, his company isn’t asking communities to contribute to a new venture, as the MRC is with the member community fund, Knudsen said.

“If you give me $30 million, I can do a lot with my tipping fee,” he said.

The $25 million MRC is managing for the communities is their money and communities should decide how to spend it, he added. “It was a stabilization fund, but they haven’t had to use the money because PERC is being operated so well,” Knudsen said.

But other companies also have stepped into the mix. The company ecomaine, which operates a waste-to-energy plant in Portland owned by a number of cities and towns in southern Maine, has proposed to dispose of Waterville’s waste for $70.50 a ton with a 20-year agreement or $57.85 a ton for a shorter term, according to a December letter to City Manager Mike Roy.

However, there are concerns about the capacity of ecomaine to handle Waterville’s trash, and expensive hauling fees are also a problem, Roy said.

There is also the only commercial landfill in Maine, Crossroads in Norridgewock, which is owned by Texas-based Waste Management.

Crossroads is already part of the mix. It is the backup option for the MRC plan, which calls for sending about 20 percent of the waste there at $62 a ton in case the proposal falls apart, Aronson said Wednesday at the Waterville meeting. PERC landfills about 30 percent of the waste it receives, he said.

WOULD HURT RECYCLING

The National Resources Council of Maine, the state’s largest environmental group, also has weighed in against the Fiberight plan.

In a commentary in the Bangor Daily News, Sarah Lakeman, the council’s Sustainable Maine project director, wrote that the best option would be for communities to stick with PERC and work on municipal compost, recycling and waste separation programs. Fiberight is proposing game-changing technology, but the technology hasn’t proved to work and the company has had a hard time getting a similar project off the ground in Iowa, Lakeman wrote. The proposal also would reduce the incentive for waste reduction and municipal composting, because the plant relies on organic matter, she added.

The Fairfield Town Council apparently already has decided it doesn’t want a part of any future waste management arrangement. Town Manager Michelle Flewelling said that although it has not taken a vote, the council will opt to let the PERC contract lapse in 2018 and not sign a new agreement. Instead, the town will abandon its current system, in which private haulers are paid a subsidy from the town to deliver trash to PERC to fulfill the town’s guaranteed annual tonnage.

The town will ensure residents can bring their trash and recycling to a local transfer station and private haulers will take care of the rest, she said.

“It put us in a decision to basically say, ‘We’re out of the trash business,'” Flewelling said. “It’s a completely different way of thinking about the entire process.”

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.