CARRABASSETT VALLEY — Snaking steeply up a ridge above the Carrabassett River’s south branch, the Appalachian Trail isn’t a hike, it’s a rock climb: tiring going up, unnerving going down.

If not for white blazes on granite, a hiker could clamber off the trail on the way up. On the way down, a missed step could mean a snapped ankle or something worse, like a tumble off the narrow trail.

“There’s plenty of opportunity to injure yourself,” said David Lowe, 56, a hiker from Greenville, N.C., who set out recently from Baxter State Park, southbound to the trail’s end, nearly 2,200 miles away in Georgia. “I will be reminding myself out loud to pay attention because if I don’t, I won’t be making it to Georgia.”

Not that Lowe’s nervous: If he completes this trip on schedule, it will be his third hike of the entire trail in four years.

Lowe, who goes on the trail by El Flaco, loosely translated Spanish for “the thin man” — he’s a skinny guy — said it’s all worth it as he sat on rocks Wednesday afternoon near the shore of the picturesque Carrabassett River’s southern branch, eating store-bought cinnamon doughnuts.

“I think the beauty far outweighs any peril.”

But it looks more and more like peril found trail hiker Geraldine Largay as the days pass since her disappearance.

Largay, 66, of Brentwood, Tenn., started out from Harpers Ferry, W.Va., in April, hiking north toward Maine. She’d already done the southern half of the trail, and finishing the northern half was an item on her bucket list.

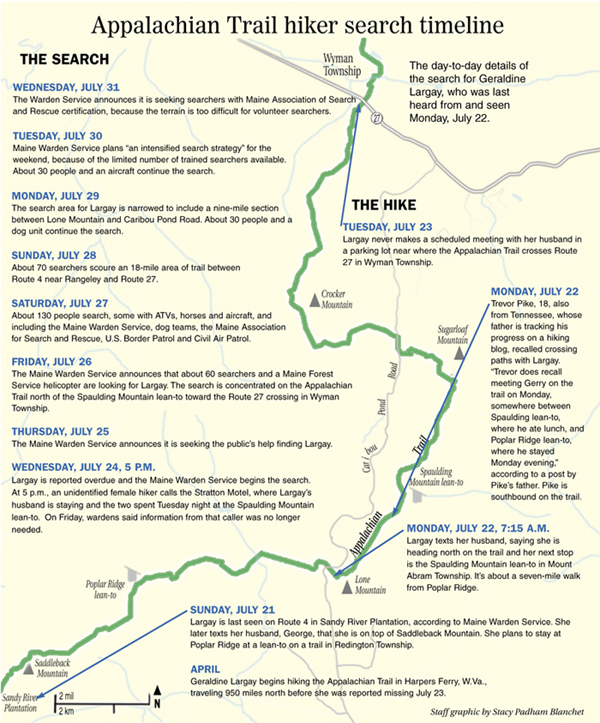

Largay made it about 950 miles, with about 200 more to go, when she vanished on a stretch of trail between Route 4 near Rangeley and Route 27 in Wyman Township around July 22.

Lt. Kevin Adam of the Maine Warden Service has called the search for Largay mystifying, saying almost all hikers who disappear from the trail in Maine are found within a day.

The rugged, steep terrain just off the trail in Franklin County, rife with treacherous basins, has hampered the search effort. As the search passed the seven-day mark late last week, the Maine Warden Service said they’d gone as far as they could with the searchers available because of the challenging landscape, and put out a call for trained volunteers to help over the weekend.

“The logistical and physical challenges associated with this remote search area restrict our ability to use searchers without formal training provided by professional SAR organizations,” said Warden Service spokesman Cpl. John MacDonald in a news release Tuesday night.

Last to see Largay?

George Largay had been following his wife’s progress via text message throughout her trip north, and the two had prearranged meetings where he would stop to help her resupply.

Largay’s goal, given her gender and age, is uncommon: only 604 women have completed the trail in sections within a 12-month period, or at least reported they have. Of those women, 25 percent were in their 60s, according to Appalachian Trail Conservancy data.

Those section hikers — people who complete the trail in multiple trips over a period of time — are typically a generation older than “thru-hikers” — those who hike the entire trail in one trip. The median age for a thru-hiker is 27. The median age for a section hiker is 55.

Twenty-five percent of the more than 13,000 hikers who have reported completing the trail are women, but women make up a much more equitable share of section hikers, said Laurie Potteiger, information services manager of the conservancy.

On July 21, Largay left Sandy River Plantation, near Rangeley, and texted her husband that she was on top of Saddleback Mountain. She last texted him on July 22, saying she planned to meet him at the Route 27 crossing in Wyman Township, about seven miles north on the trail, the next day. She never arrived.

Failure to arrive, especially on a tight deadline, worries one guide.

Phil Poirier, of Livermore Falls, who has extensive experience on the trail, said hikers are unlikely to interrupt their progress.

“Any kind of diversion at that point is unwanted. They’re just ready to be done,” he said. “It’s alarming that she has gone missing.”

On Monday, wardens narrowed the search area from a 14-mile stretch to a nine-mile stretch from Lone Mountain in Mount Abram Township to Route 27, saying the stretch south of the crossing is the area of highest probability to find Largay.

Trevor Pyke, 18, of McDonald, Tenn., hiking from Maine to Georgia with two friends, may have been one of the last people to see Largay. He reported passing by her July 22 somewhere between Poplar Ridge and Spaulding Mountain.

On July 28, Pyke’s father, Thomas Pyke, wrote on a blog that Pyke and his friends spent a long day atop Sugarloaf and Lone mountains helping wardens with the search.

Up until Friday, wardens were investigating a call placed to the Stratton Motel on July 24, in which an unidentified woman referenced the fact that Largay, whom she referred to by Largay’s trail name “Inchworm,” was late meeting her husband. On Friday, wardens said information from that caller was no longer needed.

Spokesman John MacDonald said the Warden Service had made “considerable progress” contacting hikers who’d seen Largay. By the end of the week those hikers were found as far north as the 100-Mile Wilderness — the last section of the trail before Baxter State Park — and in Baxter itself. No details on what those hikers may know was made public.

The Warden Service is holding a press conference at Sugarloaf Mountain Resort Sunday morning.

Thomas Pyke said his son’s encounter with Largay was unremarkable. There was little conversation and while Largay was alone, she didn’t seem under duress.

“It would be great in retrospect if they had stopped and talked, but it wasn’t one of those,” Pyke said. “Had that happened, it probably wouldn’t have been anything other than confirming she was OK.”

‘You’re going to fall’

The stretch of trail between Route 4 and Route 27 is steep and challenging, but Poirier said there aren’t many particular hazards on the trail. Off it, wardens have said, there would be.

The trail traverses many of Maine’s tallest mountains, including Saddleback and Spaulding, elevations 4,121 feet and 4,009 feet, just missing Sugarloaf — the state’s second-highest peak at 4,237 feet, with a resort and ski slopes on the north side but remote on the south and west — to turn toward the Carrabassett River’s south branch as the trail heads north to the state’s highest peak, Baxter Peak on Mount Katahdin.

Maine’s 281 miles of the Appalachian Trail, along with parts of New Hampshire, are considered by many to be the toughest on the trail.

“There’s no disputing” that fact, said Potteiger, of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

Adam, of the Warden Service, has said that while Largay is an experienced hiker, this was her first time on the trail in Maine.

Potteiger said hikers who haven’t hiked the northern part of the trail often struggle to prepare for the steep climbs of Maine. While the southern half has steep elevation gains, climbs are more gradual. On that half, there aren’t many climbs like the ridge over the Carrabassett River.

The trail in Maine is “rough in a sustained way,” Potteiger said. “Rock climbs are rare on the southern half of the trail and they don’t last as long.”

The trail is also narrowly cut in western Maine. A two-mile area along a ridge connecting Spaulding and Sugarloaf is so difficult it was the last part of the trail to be blazed, in 1937 by a six-person crew from the Civilian Conservation Corps.

“Soils are so thin that they just don’t lend themselves well to the kind of trail-building techniques that can be used in other places,” Potteiger said. That means conditions in Maine can be slipperier, rockier and more treacherous for hikers who aren’t experienced with that kind of terrain.

No matter the landscape, however, every hiker is going to have close calls, especially as fatigue sets in on longer treks.

“I’ve fallen, but I’m very careful near ravines and cliffs,” said Nancy Stetson, of Pittston, who hiked the entire trail in 1996. “Any time you’re hiking, it’s going to be a liability.”

Lowe, the hiker from North Carolina, said he heard one story on the trail of an experienced hiker pulling a boulder down on himself on Mount Katahdin, ending a southbound hike on the trail before it really started.

“Whatever your skill level is, there’s a degree of luck involved,” he said, “because you’re going to fall.”

‘The trail provides’

Like the wardens, those familiar with the trail are surprised by the search’s length without results, good or bad.

“People just don’t go missing on the trail this way,” Potteiger said. “It’s well-traveled and generally well-marked in the prime hiking season.”

Wardens haven’t ruled out foul play in Largay’s case, but they have said it is likely that she got off the trail herself and got lost. Before they find her, they can’t speculate much. But Adam has said foul play on the trail is rare, and hikers say danger barely crosses their mind.

Last year, a 20-year-old New York hiker drowned while swimming in Pierce Pond in Bowtown Township, near Caratunk. On July 29, a North Carolina man was found dead, apparently of natural causes, in his tent on the trail in New Hampshire.

But what the trail takes is far outweighed by what it gives, hikers say.

Lowe talked about instances of “trail magic” — a tradition of charity between those on and around the trail. He’s been given rides into town before he put his thumb out to hitchhike, he said. Those in trail towns have offered him and others beds to sleep in and food to eat.

Once on the trail in Maine, he found a Braeburn apple, still with the sticker on it. He picked it up and ate it.

“I’m, by nature, a cynic, but being on the trail has completely restored my faith in humanity,” he said. “The trail provides.”

News also travels quickly up and down the trail, Lowe and Stetson said. Hikers going it alone aren’t really alone — there’s a close community on the trail. Stetson said she spent every night of her 1996 hike with hikers she ran into along the way until she got to Maine. That night, the 165th of her hike, she finally spent alone, at Crocker Cirque in Carrabassett Valley, a logical last resting place before the Route 27 crossing in Wyman Township.

Largay should have passed by there on the way to meet her husband. She almost certainly didn’t get that far.

Just south on the trail from there, hikers must ford the south branch of the Carrabassett River. Stetson said that can be one of the trail’s biggest dangers in high water.

Tuesday and Wednesday, July 22 and 23, it rained most of the day in the area, and the river may have been high.

However, last Thursday, more than a week later, the water was low. The channel was easy to traverse on a board between rocks, suspended by metal cables. It isn’t likely Largay made it there, either.

Just after the river crossing headed north, hikers quickly cross Caribou Pond Road, a popular access point to the trail for day hikers. Hikers who follow the road would end up at Route 27, a mile from the entrance to the Sugarloaf resort — civilization.

But wardens have swept that area as well for Largay, to no avail. All that has made the hiking community rally for the best possible outcome.

Wardens have said many have volunteered to search for Largay. Wednesday, they put out a call for searchers with Maine Association of Search and Rescue certification. The Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel have received emails about the search from as far away as Georgia and Tennessee.

Stetson said hiker friends from the South have been following news articles about the search that she has posted on her Facebook page.

When she was on the trail, hikers would sometimes get lost for a day or two, then come back onto the trail. She’s never heard of anything like this.

“We’re all praying for her,” Stetson said. “It’s just bizarre.”

Michael Shepherd — 370-7652

mshepherd@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story