“We sort of made a pact,” Heidi Chadbourne said, “that when you join this group, if you’re available, you go.”

And in the winter of 2012, when the call came — a woman in her 50s, suffering from a terminal illness, near death — Chadbourne and three other members of her team were available. So on a cold and dark evening they went to the woman’s house on a dirt road in central Maine.

Harry Vayo, 58, the group’s leader, knocked on the door. Tall and owlish, with spectacles and good posture, Vayo taught chemistry at Oakland’s Messalonskee High School for more than 20 years.

Inside, a burly man on a couch welcomed them. In the bedroom, the atmosphere was very still and quiet. The woman lay on a bed, her mother and another woman holding her hands as they stood vigil. The dying woman didn’t make eye contact or give any sign she knew there were four strangers standing in her bedroom.

The group didn’t know the specific nature of the woman’s illness but it was clear she wasn’t doing well, with every irregular breath a struggle.

Vayo introduced the group and their members, and then opened his mouth: mysterious Gaelic words and haunting high notes and soothing repetitions. An ancient Celtic tradition, the song, “Caim agus Curragh” translates roughly as “Shelter and Boat.”

“It kind of has the idea of the shelter as security and yet the boat implies a journey, a transition,” Vayo said. “I think of it as kind of a metaphor for the process of dying. You’re hopefully surrounded by those you love but you’re going off into the unknown.”

After the first verse, Chadbourne and the other singers joined in, softly, fulfilling an act they considered to be not a performance, but a service and a sacred duty.

“You’ve come through the night,” Chadbourne said. “You’ve come through the dark. You’ve come through the woods and now you’re in a very, very, very warm place and everyone is grieving. Now you’re in the room. It’s not nerves or fear, but you really want to do a good job.”

The group sang seven songs, all with brief repetitive lyrics from traditions and faiths — Celtic, French, Latin, African — that span the globe.

The final note of the final song sounded. The woman on the bed gave no sign that she had heard them. It was time to leave.

Within an hour of the group’s departure that night, the woman died.

Chadbourne said the experience was a reminder of an uncomfortable truth in modern-day America: “We’re all in the act of dying.”

It was also one of dozens of times that the group has performed for Waterville and Augusta area hospices over the last several years. They are the Tourmaline Singers, named for Maine’s official state gemstone, which was also once thought to have healing power.

Vayo believes that music has healing properties that can help improve a wide range of medical issues, a proposition that has it backers in both the scientific and religious communities. The idea, referred to broadly as music therapy, has begun to gain ground in scientific circles over the past 20 years.

The Tourmalines aren’t unique; they are part of a New England trend that’s gained momentum in recent years following a conference and workshops about hospice choirs.

Sometimes the Tourmaline Singers go somewhere to talk about their shared experience over a cup of tea, but that December night the quartet of singers just sat in the car and spoke to each other about what they had seen, what they had felt. “My main concern was that everybody else was doing OK,” Vayo said. “It’s pretty strong stuff.”

Chadbourne described the experience as sacred.

“It’s very sad,” she said. “Very, very sad. But I’m glad I had the opportunity to do that. I think we imparted some hope and promise and joy.”

EMERGING HOSPICE SERVICE

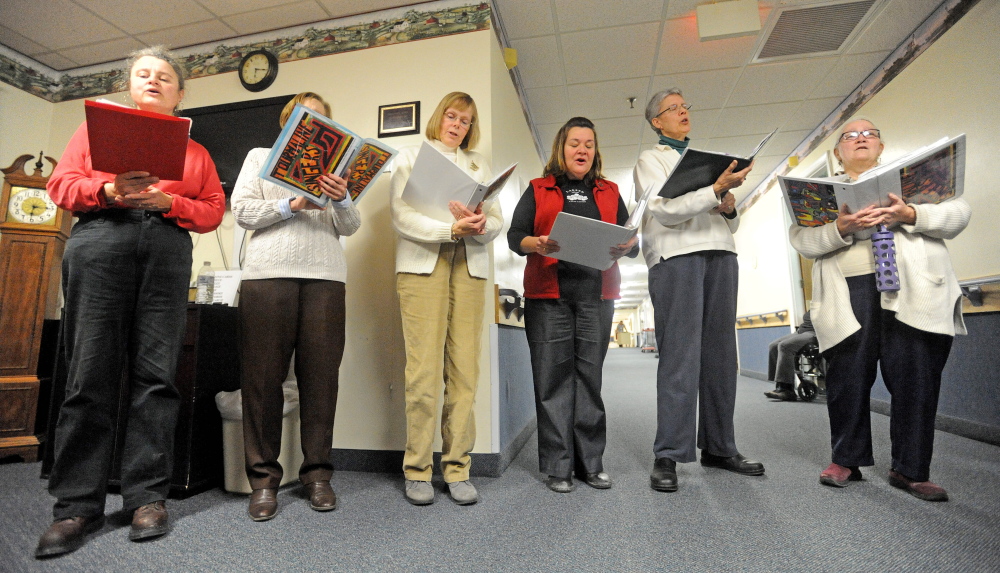

Every Friday night, about a dozen Tourmalines gather on the second floor of the United Methodist Church on Waterville’s Pleasant Street for a two-hour rehearsal.

The atmosphere is cheerful — warm greetings exchanged in a cool room, laughter and small talk springing up between songs. The group has more retirees than younger people, more women than men, and draws members from Benton, China, Manchester, Oakland, Waterville and Winslow.

They’re in a Methodist Church, but only a few of them are Methodists — Baptists, Quakers, Unitarian Universalists and Native American spiritualism are all represented within the group, which believes its mission transcends any particular faith.

“Everybody’s a slightly different theology,” said Chadbourne, of Manchester, who is an inspector at the State Department of Agriculture. “I love this group because we have people from more conservative traditions and more liberal traditions and I think that’s great.”

The Tourmalines formed in 2007, the same year The Pathway Singers formed in New Hampshire’s Monadnock region and another, Heartsong, formed in Belfast. In 2008, both the Harbour Singers of the Saco-Biddeford area and Evensong, an official service offered by the Hospice Volunteers of Hancock County, were founded.

The similar timing of the formation of the groups was not a coincidence.

The roots of the fledgling movement lie with the Hallowell Singers, a group that formed in Brattleboro, Vt., in 2003. In 2007, the Hallowell Singers’ story was presented during a professional hospice conference and later that year, they held a workshop in the very same Waterville church the Tourmalines now use as a rehearsal space. More than 60 people attended, many of whom went on to form their own choir groups.

The groups have been well-received and seem to fill a need, which has led to more growth, according to Gerry Gespersen, co-director of Evensong. That group was so successful that it recently split into two groups, Evensong East and Evensong West, which sang to a total of 65 different individuals or groups in 2013. Another group, the Solace Singers, began in Knox County in 2011.

Vayo said representatives from many of the groups came together informally in 2013 to compare notes and learn from each other.

Within the group, which Chadbourne sometimes leads in Vayo’s absence, there is a strong sense of camaraderie.

“I consider them dear, dear friends,” Chadbourne said. “I have the greatest respect for this group. I’m so thankful to be able to fit in.”

During the rehearsal, the group members sang a capella, standing around Vayo in a rough semicircle, bouncing to his rhythm and checking their songbooks only occasionally as they practiced for the next time their services would be called upon.

“Sing to the power of the faith within!” they sang. “Lift up your voice! Be not afraid!”

Lately, they’ve been getting calls to sing about once every month or two. They are not sure when the next call will come, but when it does come, they want to be ready.

THE SCIENCE OF FAITH

Vayo, with his unfailing positive energy and unflappable calm, is an ideal leader for the group.

Vayo is not a fully credentialed music therapist, but he is a certified music practitioner, a title he received after being trained to play healing music at the bedside of the sick and dying by the New York-based Music for Healing and Transition Program. His work with the Tourmalines, he said, is separate from his work as a practitioner, but they are both based on the idea of music as a medically important treatment method.

There is no way to prove what impact, if any, the Tourmaline Singers had on the final minutes of the unresponsive woman who lay dying on her bed.

But Vayo, and the program that certified him, say science does show that music improves health. Its website lists about 100 research studies, most of them published in peer-reviewed journals over the last 20 years, that have measured the positive impact of music on everything from infant birth weight to pain levels. The studies show music can improve the efficiency of an MRI, reduce the number of outbursts of an agitated dementia patient and improve the memory of people with Alzheimer’s.

Much of the impact seems to be from the power of music to distract patients from pain and discomfort, trigger their emotions and help them connect to the world and people around them.

“This is a little different from music that eases the dying process,” Vayo said. “Music can help do things like boost the immune system, to help lower blood pressure and help in the release of endorphins, which are sort of natural painkillers.”

The Tourmalines field calls from area hospices, including Beacon Hospice in Augusta, and Hospice Volunteers of Waterville Area, or directly from family members who have found one of their brochures in a church pew or heard about them from a friend.

Vayo keeps scrupulous notes from every visit, in part so that if they are asked to return to someone, he’ll know what they’ve already sung.

As Vayo leads the group in song, he exudes both poise and kindness in equal portions, two character traits that have inspired confidence from the group’s members. The ease with which he describes concepts hint at a deep reservoir of knowledge about both music and hospice care.

If the group gets on edge, as happens sometimes, Vayo might lead them back to a state of calm by sharing a bit of music trivia, such as the origin of the song “Silent Night,” or explaining a bit of musical jargon.

One of the many vital roles Vayo performs for the group, more important than keeping them in tune with the pitch pipe he always keeps at hand, is guiding them through the potentially awkward scenes that often come with someone who is very sick.

When a person is relatively healthy, the songs are more upbeat, like the Les Brown classic “Sentimental Journey.” Sometimes they walk into a home expecting to perform something light, only to find that the person is much worse off than they had expected. In those cases, Vayo changes his tune — literally, by swapping out upbeat songs designed to entertain in favor of melodies that are more appropriately somber.

“When somebody is that close to death, it’s very important not to do anything to kind of pull a person back in the other direction, once a person has started that natural process,” Vayo said. “What we try to do in that situation is to support the person who is actively dying and help ease that transition. We sing very simple music. We don’t sing four-part harmony in a case like that. We wouldn’t sing intricate rounds. We would probably just sing something very, very simple, with some simple repetitive words.”

Vayo, too, is the one who leads them through the post-sing debriefing session that they have built into the process.

“When we’re singing for a person who is actively dying, it’s very important for us to take care of ourselves,” he said. “We just gather together and kind of talk about the experience, the things it brought up and supporting each other.”

A HOLIDAY VISIT

Two weeks before Christmas, on Dec. 13, Kay Squires sat in a chair beside her bed in the hospice wing at the Augusta Center for Health and Rehabilitation, picking at her dinner.

She had been there for about a year, after living for more than a decade at St. Mark’s Home for Women, an independent living home on Augusta’s Winthrop Street. Squires expected the rehab center’s hospice wing would be her final address.

“I think I’m here for life,” she said.

She raised her voice to her roommate, sitting on the other side of the room. “Maddie, are we here for life?”

“I’m afraid so,” her roommate, 88, answered. Then added, wryly: “How I got in this predicament, I’ll never know.”

Squires and her roommate, Madeline Hamilton, of South China, asked to live together, and are pleased with the arrangement.

“They’re like peanut butter and chocolate,” Squires’ daughter, Martha Holzwarth, of Windsor, said.

At 91 years old, the small, frail Squires has led a full life. She grew up in Connecticut and landed a job as a gym teacher at a junior high school. She’s also played the second violin in the Norwalk Symphony Orchestra, raised a family and traveled extensively.

Now, Squires is suffering from problems with her lungs. She eats only a few bites from the plate of roast beef and mashed potatoes.

Squires received a visit from the Tourmaline Singers once before. They made her happy, so she asked them to come back and bring her some holiday cheer.

After Vayo, Chadbourne and a group of about 10 singers set up in a community room to perform, Squires assumed the role of hostess. She asked Vayo slightly formal questions to which she already knew the answer, her way of making sure that the three or four other audience members were engaged and fully enjoying the experience. When she expressed gratitude to the singers, it was on behalf of the entire small audience.

“Thank you for coming out on such a not-nice night. We appreciate you.”

Vayo worked with Squires in trying to engage everyone, speaking briefly between songs.

When the Tourmalines finished “Dona Nobis Pacem,” Latin for “grant us peace” and used in Catholic Mass, it was followed only by the thin sound of one person clapping.

Vayo, Chadbourne and the other singers were undeterred. They weren’t there for applause.

Vayo told the audience the meaning of the words in their next song, “Thula Klizeo,” from West Africa: “Be still my heart. Even here, I am at home.”

Then he moved on to more familiar material as other residents, drawn by the music, began to enter the community room, one at a time, some in wheelchairs. The enthusiasm of the singers and the quality of their songs began to have an impact.

Somewhere around “What a Wonderful World” or “Joy to the World,” the audience began to join in, singing snatches of the chorus, mostly when no one was looking.

By the time the Tourmalines got to the final songs — “Silent Night,” “O Come, All Ye Faithful” and “Deck the Halls,” to mark the season — the audience members outnumbered the performers, and many of them were singing openly.

Squires once again assumed the role of hostess.

“Let’s give them a nice hand,” she said at the end, leading a final round of applause.

After the Tourmalines left for what promised to be a lighthearted debriefing, Squires returned to her room, enlivened.

The Tourmalines had reminded her of her love of music, of its power to do so much with so little.

“Do you realize that music is made up of only seven notes?” she asked. “All the music we know — ABCDEFG — seven notes? Jazz, anything, Seven notes. Sharp, flat. Fast, slow. Seven notes. Now, if that’s not a miracle, I don’t know what is.”

DIFFERENT VIEW OF DEATH

Hospice singing is not always easy.

“It’s not a place of comfort right away,” Chadbourne said. “If it’s a place of comfort at all.”

The mission of the Tourmaline Singers brings them face to face with death, a sometimes taboo topic in modern-day America.

While the idea of death discomforts many people, the hospice industry is making an increasingly strong case that it’s important to acknowledge that all people die, Vayo said.

“We’re trying to help our culture understand that death is not necessarily the enemy. Death is as much a part of life as birth is,” Vayo said. “Of course, we all want to have long, healthy productive lives, but there comes a time to let go and that’s OK.”

Vayo said he sees signs that death, which has been swept under the carpet for decades, is returning to its proper place in society’s consciousness. One small part of that story is the presence of hospice singers like the Tourmalines, who have each made the individual choice to open themselves up to the experience of dying.

“When I do this kind of work, this kind of singing, it blurs the distinction between giving and receiving,” Vayo said. “It’s just sharing, in a very deep and meaningful way.”

Chadbourne said it has been an enriching experience for her.

“Sometimes there are benefits that you don’t imagine, things that come through in an unexpected way. Every time I go, I’m really glad when I’m leaving.”

Now, she doesn’t see death as a harsh departure.

“I have a lot of hope. I don’t have anything concrete I can point to. Who of us can? I mean, I haven’t been through that yet. But I think that process can be one of gentleness and acceptance and a sort of good.”

For many of the people who have heard the Tourmalines, the visit is a pit stop near the end of a physical and mental decline. That’s one reason why, Chadbourne said, it’s sometimes better not to know the person outside of the context of the singing. It’s simply too painful.

That decline is something the singers have come to expect. Generally speaking, the people they sing to will get worse, not better.

But not always.

Squires, the violinist and gym teacher with no appetite, will continue on life’s journey, according to her daughter.

The 91-year-old came off of hospice care in Augusta in early March and is now doing well.

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling — 861-9287 mhhetling@centralmaine.com Twitter: @hh_matt

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story