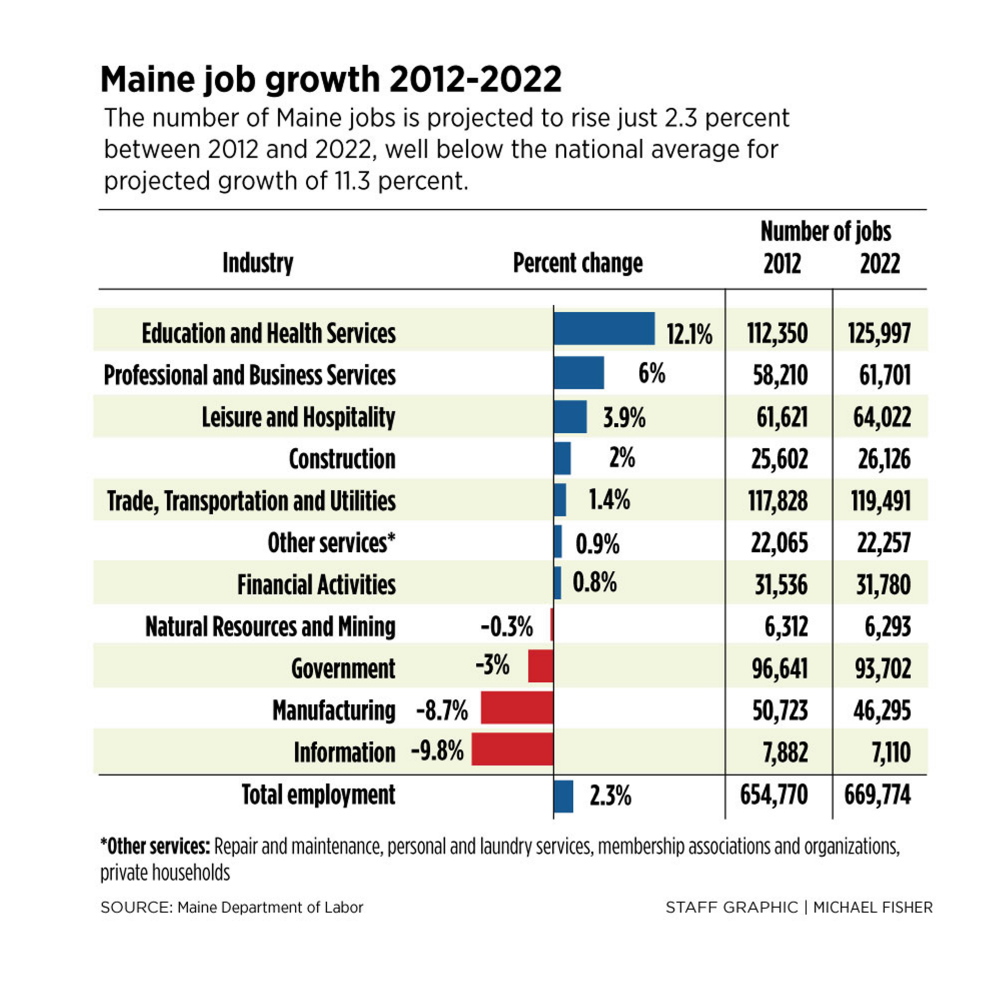

In yet another sobering indicator of economic performance, Maine is expected to lag far behind the nation in job growth for the next decade.

The state is expected to add just 15,000 jobs between 2012 and 2022, an increase of a mere 2.3 percent – far below the national projection for average job growth of 11.3 percent for the same period.

The forecast by the Maine Department of Labor largely blames a “demographic challenge” for the dismal job-growth figure, saying the combination of an aging population and the lack of significant in-migration by younger people will lead to a decline of 1 percent in the size of the labor force by 2022. The lack of available workers would make it difficult for businesses to grow.

“If we do not foster an environment that will entice higher rates of in-migration to stem this demographic tide, we will see outright decline (in job growth) longer-term,” a department report accompanying the projection stated.

The projection says the battered manufacturing sector – which includes the hard-hit paper industry – will continue shedding jobs, losing another 8.7 percent by 2022. In 1982, manufacturing was Maine’s largest sector and generated 109,000 jobs. By 2022, the Department of Labor projects there will be only 46,300 manufacturing jobs in the state.

The information sector that includes publishing, broadcasting and telecommunications will do even worse, according to the projection, with employment declining 9.8 percent over the decade.

Sectors projected to add jobs by 2022 include health care and social assistance, which the department said will employ 113,600 people in 2022, up from 100,500 in 2012. Professional and business services will provide 61,700 jobs in 2022, up from 58,200 in 2012. Modest job gains are forecast for the state’s leisure and hospitality industry and private educational services.

Construction will add 500 jobs, to 26,100, by 2022, the department’s projection said, but will remain below the number of jobs before the 2008-09 recession. Likewise, retailers will add about 1,200 jobs, to 82,400, by 2022, but also will have fewer jobs than before the recession.

PREGNANT PAUSE IN POPULATION GROWTH

Glenn Mills, chief economist at the department’s Center for Workforce Research, and Charles Colgan, chair of the Community Planning and Development Program at USM’s Muskie School of Public Service, agreed that stagnant population growth and falling birth rates are to blame for the expected slow job growth.

“It’s really more a function of your working-age population,” Mills said. “We are too constrained because we stopped having enough kids in the ’90s.”

Mills declined to describe the projection as good or bad, saying it reflects the department’s best forecast on job growth over a decade. He said there are some positive outcomes from slow job growth, including falling unemployment rates because of the contraction of the labor force. With fewer working-age people, the jobs that are created will probably pay better, he said, or employers will have to go out of state to recruit workers with the right skills.

Colgan believes the department might be painting too dark a picture.

He said the past 10 years have been largely flat in terms of total population in the state, but he thinks population growth will pick up again, partly because employers will have to offer better wages to keep or attract workers.

“If you allow the labor market to work, it’s not quite so dismal,” Colgan said. “In my judgment, the next 10 years will be different from the last 10 years.”

The effort to recruit workers from away is already taking place in Maine’s technology sector, said Jess Knox, president of the business consulting firm Olympico Strategies and founder of Maine Startup and Create Week, an annual gathering of entrepreneurs.

“The issue of attracting young people to Maine was first mentioned in (Joshua) Chamberlain’s inaugural address, so it’s not new,” Knox said, referring to Maine’s governor in the late 1860s.

He said recruiting is already a big focus of Startup and Create Week, but the effort continues year-round. The key is getting the word out about opportunities in the state, particularly for Maine natives who left for college or jobs, Knox said.

But Joel Johnson, an economist with the Maine Center for Economic Policy and a member of the state’s Consensus Economic Forecasting Commission, said a situation in which companies are recruiting high-wage talent from out-of-state for few available jobs will only exacerbate the wage gap.

He said manufacturing offered the kinds of jobs “where workers that didn’t have advanced skill-sets could find high-wage work.” State policymakers need to consider programs that could help the state attract those kinds of opportunities, Johnson said.

“We need to figure out how to get median-wages-and-below growing again” and avoid “unbalanced growth that the report’s projections suggest,” he said.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.