NEW YORK — Thirty-five years after New York City first-grader Etan Patz vanished on a short walk to his school bus stop, sparking a national missing children’s movement, a Manhattan prosecutor called it a “crime that changed the face of this city forever” in opening arguments Friday in the murder trial of a former bodega clerk whose attorneys say is mentally disturbed.

“Etan was dead before his mom even knew he was missing (and) then his family and countless others spent the next three decades looking for him,” Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Joan Illuzi-Orbon told jurors Friday. “That journey ends here.”

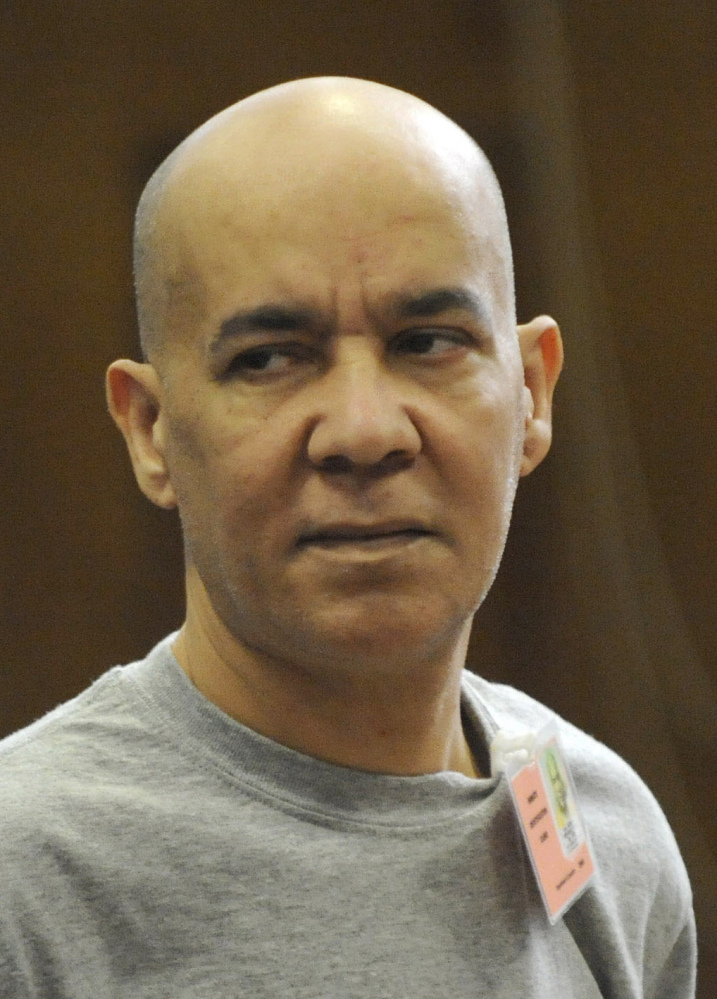

Prosecutors say Pedro Hernandez, 53, who was a teenage clerk at a bodega near Etan’s bus stop, lured the boy into the store’s basement with the promise of a soda, and then strangled him. Hernandez made a videotaped confession in 2012 and re-enacted the crime for investigators.

HEART-WRENCHING SEARCH

Hernandez’s arrest, 33 years to the day after Etan disappeared, upended a long-held and widespread belief among many – including law enforcement officials, the boy’s parents and a New York civil court judge – that another man was responsible.

For years, the heart-wrenching search for Etan riveted the nation. The blond, blued-eyed child was among the first missing children to appear on a milk carton.

Defense attorneys for Hernandez say he is mentally ill with a very low IQ, and they contend that a videotaped confession he gave police after six hours of interrogation was coerced. Attorney Harvey Fishbein told jurors they would see no forensic, physical or eyewitness evidence linking Hernandez to the disappearance.

Etan had been bugging his parents to let him go alone for days, and on that day in May 1979, his mother relented.

Prosecutors said the little boy apprenticed as a junior carpenter with local handyman Othniel Miller and had earned a dollar working in Miller’s basement shop the night before he disappeared. Etan left home the next morning with the dollar, telling his mother he was going to stop at the bodega to buy a soda before getting on the bus.

When he failed to return home from school, a massive search was launched, and hundreds of police and volunteers blanketed lower Manhattan looking for him. Stan Patz, a commercial photographer, had recently shot a series of poignant photos of his son and soon the boy’s cherubic face graced missing posters and newspaper front pages across the country.

THE OTHER SUSPECT

In 1982, investigators began looking at Jose Antonio Ramos, a mentally disturbed Bronx man. He had dated one of Etan’s babysitters, who would later accuse him of molesting her son. Police learned that Ramos had tried to lure some boys into a drainpipe in the Bronx and found pictures of young boys resembling Etan inside the pipe. Ramos also made incriminating statements to authorities, but never admitted to killing the boy – leaving prosecutors without enough evidence to charge him.

In 2001, Etan’s parents had their son declared legally dead so they could sue Ramos in civil court. In 2004, the court declared Ramos responsible for Etan’s death. Ramos served more than 20 years on a child molestation conviction in an unrelated Pennsylvania case. He has been ordered to testify as a material witness in the Hernandez trial.

Then in 2012, Hernandez was arrested and charged with Etan’s murder and kidnapping after a relative called in a tip to police. At least three witnesses have told investigators that he confessed to them to killing Etan at various times going back to the 1980s. A new witness – identified this month as a fellow inmate – is also expected to testify that Hernandez admitted to killing the child.

Experts say the Patz case helped revolutionize the way law enforcement responds to potential child abductions.

“Of course, technology has changed so dramatically and that’s had a major impact, but we have so many more resources as a result of the Patz case,” said Robert Lowery Jr. of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

“Now we have things like the FBI’s CARD (Child Abduction Rapid Deployment) teams, which are response teams specially trained by the Justice Department to deal with child abductions. . . . We have Amber Alerts, sex offender mapping software,” he said. “If Etan went missing today, we would have a world of resources to help track him down.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.