AUGUSTA — With cases of Lyme disease and mosquito-borne diseases on the rise, the state is trying to educate Maine elementary school students, one of the most high-risk age groups, about prevention methods.

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, with the help of public health graduate students, developed educational materials last year for teachers to use. An epidemiologist for the state and graduate students at Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine began visiting third- through fifth-grade classrooms around the state this month to teach the kids about the dangers of the diseases as tick and mosquito season approaches.

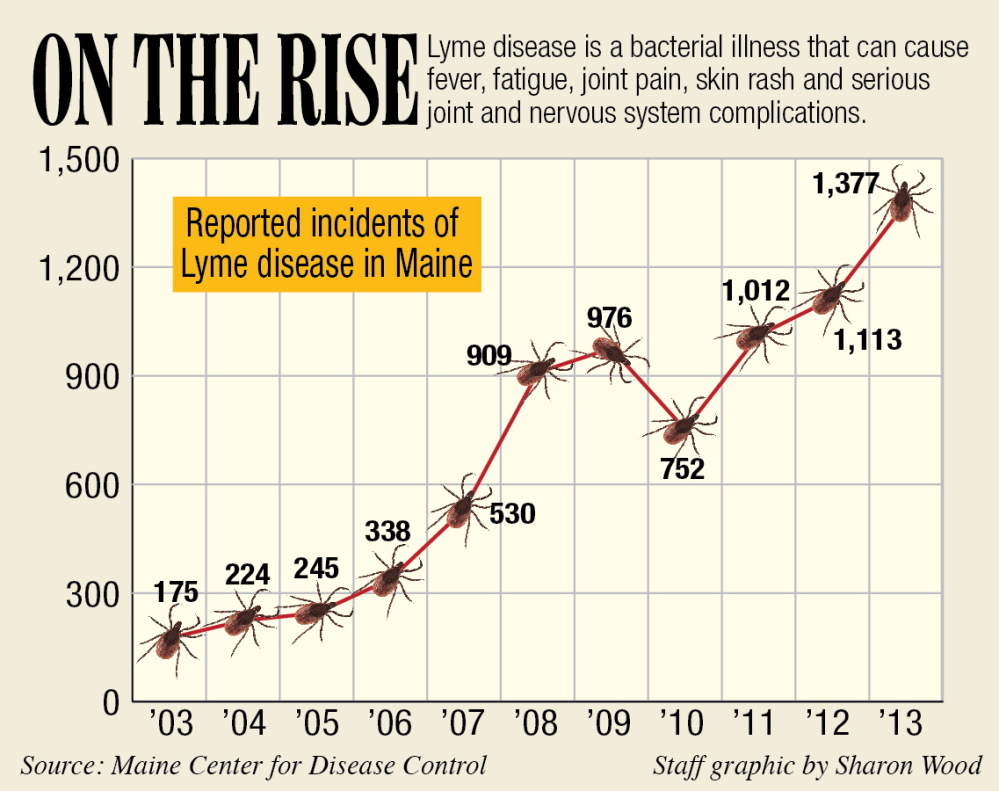

There were more than 1,300 cases of Lyme disease reported in Maine in 2013, nearly eight times more than the 175 reported a decade before, according to the Maine CDC. Children between the ages of 5 and 14 are more likely than any other age group to contract Lyme disease and about twice as likely compared to adults ages 25 to 44.

Epidemiologist Sara Robinson said this is probably because children are more likely to be outside and exposed to ticks.

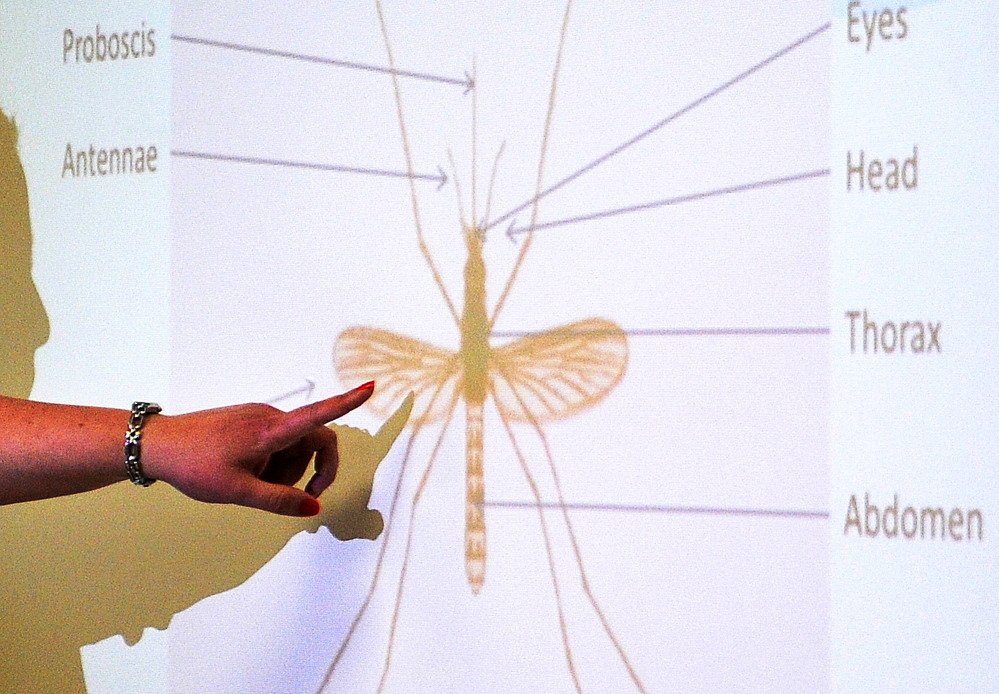

At Farrington Elementary School in Augusta, Robinson presented lessons about mosquitoes and ticks to two fourth-grade classes last week. Before the presentations Robinson and the graduate students tested the children about their knowledge of ticks and mosquitoes, and the students will be retested in a couple of weeks to see what they have retained.

The fourth-graders were curious after Robinson’s presentation on mosquitoes, asking questions about mosquito biology and the diseases the insects can spread. One inventive boy asked if mosquitoes would leave people alone if they stopped breathing out carbon monoxide, didn’t emit any heat and if mosquitoes couldn’t see.

“That is true,” Robinson told him. “But unfortunately, we can’t stop breathing. … Don’t try it.”

The program, funded by a national CDC grant for helping communities prepare for the health effects of climate change, began last year, Robinson said. Students in the Muskie Public Health Education Corps developed the educational materials, which are available on the Maine CDC’s website, and matched the lessons to Maine Learning Results, allowing teachers to show how the lessons fit in with the program, she said.

Robinson and graduate students piloted the lessons at two schools, Alfred Elementary School and Durham Community School, last year. In testing after the lessons, students improved significantly in being able to identify deer ticks, which can carry Lyme disease. Students at one school increased their ability to identify the tick from about 26 percent before the lessons to 80 percent after, Robinson said.

“Hopefully it means they’re more aware of what ticks are; they’re looking for them; they’re trying to get them off; and if they’re doing all of those things, hopefully we’re reducing Lyme disease,” she said.

Studies have shown that climate change has contributed to the expanded range of ticks, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, but climate is “just one of many important factors that influence the transmission, distribution and incidence of Lyme disease,” the agency said in materials about climate change indicators on its website.

Mosquito-spread diseases are relatively new in Maine, but mosquitoes kill more humans than any other animal, Robinson said. The two primary viruses in Maine transmitted by mosquitoes are Eastern equine encephalitis virus, known as EEE, and West Nile virus.

The first reported case of West Nile virus in the state was in 2012, and the first case of EEE was reported last year, Robinson said.

She said people tend to know more about tick-spread diseases because they’re more common than ones spread by mosquitoes. Also, people see mosquitoes as nuisances, not health hazards, Robinson said.

Most people infected with those mosquito-born viruses don’t ever show symptoms, but of those who do show symptoms after contracting EEE, half of them die and a third suffer long-term neurological damage, Robinson said.

She told the students that both diseases can send them to the hospital, and both can cause encephalitis, which is swelling of the brain.

“They can be very, very serious,” Robinson told the students. “We want to prevent these diseases from ever happening.”

For the mosquito diseases, the lessons for prevention focused on avoiding getting bitten in the first place. Students were encouraged to wear long pants and long-sleeved shirts, use EPA-approved repellent and minimize the time they’re outside during the early morning and early evening.

Students were also told to check doors and window screens to make sure there aren’t any tears or holes in them and to remove any containers outside that can collect unwanted water. For bird baths and other containers designed to hold water, the water should be changed once a week to prevent mosquito larvae from growing in the pools.

Robinson said Maine CDC is hosting a webinar for teachers at the end of this month, and she’s hoping to visit more schools. However, the goal is to train teachers to do the lessons themselves, she said.

Trevey Davis, one of the graduate students teaching the lessons at Farrington, said another advantage of speaking with younger children is that they’ll talk with their parents about it and spread the knowledge.

“(Teachers) realize it’s a win-win,” said Davis, who is in his first year at Muskie. “When their students are healthy, their communities are healthy, and that information gets spread through the community.”

Paul Koenig — 621-5663

Twitter: @paul_koenig

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.