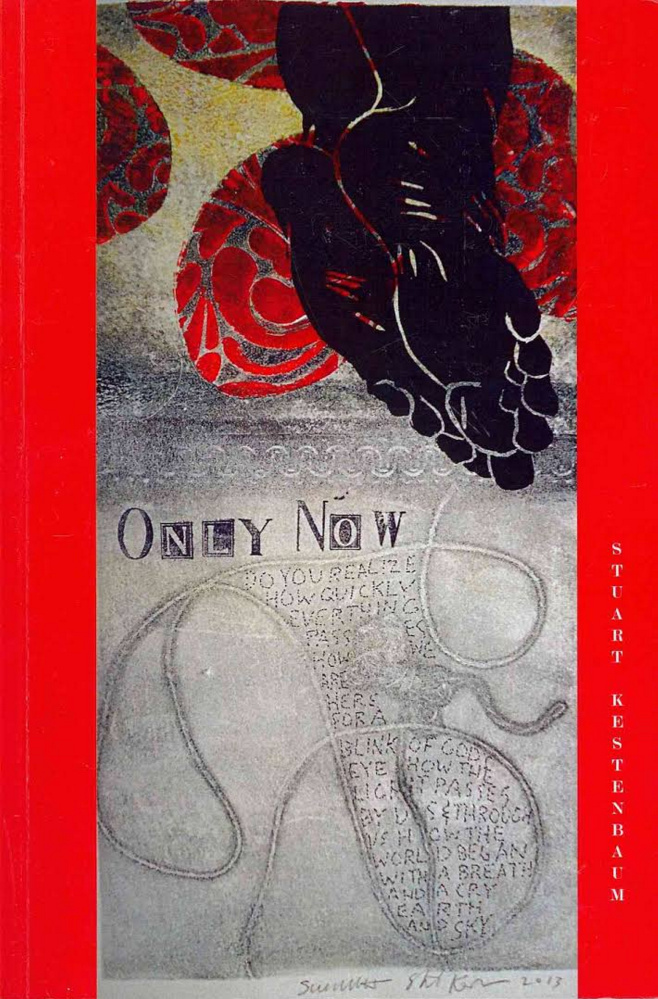

“Only Now: Poems”

By Stuart Kestenbaum

Deerbrook Editions, Cumberland, 2014

76 pages, trade paperback, $16.95

Just in time for National Poetry Month (the 20th April of its existence, by the way), the Maine Arts Commission announced in March the appointment of Stuart Kestenbaum, of Deer Isle, as Maine’s new poet laureate, a term that runs through 2020.

Kestenbaum retired last year as the director of the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Deer Isle. Along that journey of more than 25 years, he also published four volumes of poetry, including “Prayers & Run-on Sentences” (2007), “House of Thanksgiving” (2003) and “Pilgrimage” (1990); a book of essays, “The View From Here” (2012); and many poems in journals, including the esteemed Beloit Poetry Journal, which has been based in Maine for decades.

Kestenbaum’s most recent book, “Only Now,” may indicate a different tenor to the laureate’s influence than those of his predecessors. Wesley McNair, laureate from 2011 to 2015, Betsy Sholl, 2006-2010, and Baron Wormser, 2000-2005, while all possessing unique, highly skilled poetic voices of their own, at the same time shared a disposition to subtle dictions and rhythms, reflecting atmospheres of seriousness and complexity, sometimes light, sometimes shadowy amid carefully layered ironies. These sensibilities emerge in their poems at varying levels of accessibility — the creative writing workshop term for how easily a poem can be understood by your everyday, rational mind.

The poems in “Only Now” are of a different ilk. Their language is extremely direct, similar to the plain-spoken diction of Maine poet and agriculturalist Russell Libby (mentioned here a while back). Kestenbaum’s accessible sentences aim not so much at ironies, but more (in “Only Now,” anyway) toward friendly, practical exhortations to live in and appreciate the beautiful dawning moment of now.

A large number of the poems in the book, for example, are tagged “prayers” — “Prayer While Downshifting,” “Winter Morning Prayer,” “Prayer for Real,” “Prayer for Survival.” But rather than being conventional religious petitions, they instead largely contain advice for creating, maintaining or cultivating a positive disposition toward one’s immediate surroundings. “Prayer for Mistakes” begins:

The last mistake you made

is not the end of the world,

the end of the world will be

much bigger than that,

much larger than you

and the last nightmares you had

The poem goes on to reassure the listener that “your brain can take a break / worrying about the end of things / and get started on now,” good advice in everyday life.

A recurrent trope is simple awakening. “Prayer to Wake Up” begins with a dramatic image (“This morning I awake and it’s / cold in my room”), runs through a fantasy on all the heartwarming everyday stuff that’s probably happening outside, and lands finally on the image of an old woman’s broom that makes “it possible / to start anew every morning.”

Many of these poems seem to unfold along the lines Robert Frost describes in “The Figure a Poem Makes”: A poem “begins in delight, it inclines to the impulse, it assumes direction with the first line laid down, it runs a course of lucky events, and ends in a clarification of life.” In “Only Now,” you usually feel like you’re accompanying the poet on a sort of wandering saunter to see what you can learn about the day in hopes of gaining “a momentary stay against confusion,” in Frost’s phrase. Where are we headed, for example, in “Big World,” which begins, prosaically:

It’s a big world out there, big enough to encompass John Cage

and Popeye the Sailor all at once, big enough to encompass a monk

breathing the must of incense and a guy outside the bar exhaling

cigarette smoke and stamping his feet against the cold.

After running a wandering course, it concludes with childlike directness: “All you can do is tie your shoes and put one foot in front of the other. / It’s enough to make you weep, these simple steps.” This is a kind of inspirational verse, in language so plainspoken it might have been copied out of daybook entries and broken into lines.

This differs from the poetry of three previous laureates. McNair’s writing is generally very accessible, but works rhythms, diction and personal darkness in intricacies much different from what we encounter in “Only Now.” Sholl’s and Wormser’s poetics, like McNair’s, explore linguistic complexities that Kestenbaum’s does not – at least in “Only Now.” While ironies in Wormser, Sholl and McNair can be penetrating and sometimes quite dark, in Kestenbaum, when they appear, they aim for buoyancy and probity.

(Full disclosure: I omit mention of the poetry of Kate Barnes, Maine’s first poet laureate, simply because I am not, it chagrins me to reveal, very familiar with it.)

The poet laureate post in Maine is an unpaid, free-wheeling appointment with no specified duties. It looks a lot like Stuart Kestenbaum is going to bring a whole new voice to the task.

“Only Now” is available online through Deerbrook Editions, among other booksellers.

Off Radar takes note of books with Maine connections every other week. Contact Dana Wilde at universe@dwildepress.net.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.