“Hearts in Suspension”

By Stephen King, et. al.

Jim Bishop, editor

University of Maine Press, Orono, 2016

378 pages, hardcover, $30

In case you forgot or never knew, the Vietnam War officially crashed off the side of an American warship in 1975. By that time, the heat was more or less off us lower-middle-class Maine white kids. And by the heat, I mean the nightmare monster of the draft, which in the 1960s and early ’70s could suck you in and drop you in the jungle to die a horrible death. When I was in high school in the late ’60s, there was a spell where 500 American troops a week were being killed in Vietnam. That’s 500 A WEEK.

Fast-forward to 2016: The draft and its effects are kind of forgotten items — casualties in memory to two currents of historical distortion: one a fantasy-laden romanticization of the 1960s, and the other a shrewdly crafted revision of ideals of peace, love and understanding into idols of ridicule.

It’s hard to remember what was really happening in the 1960s.

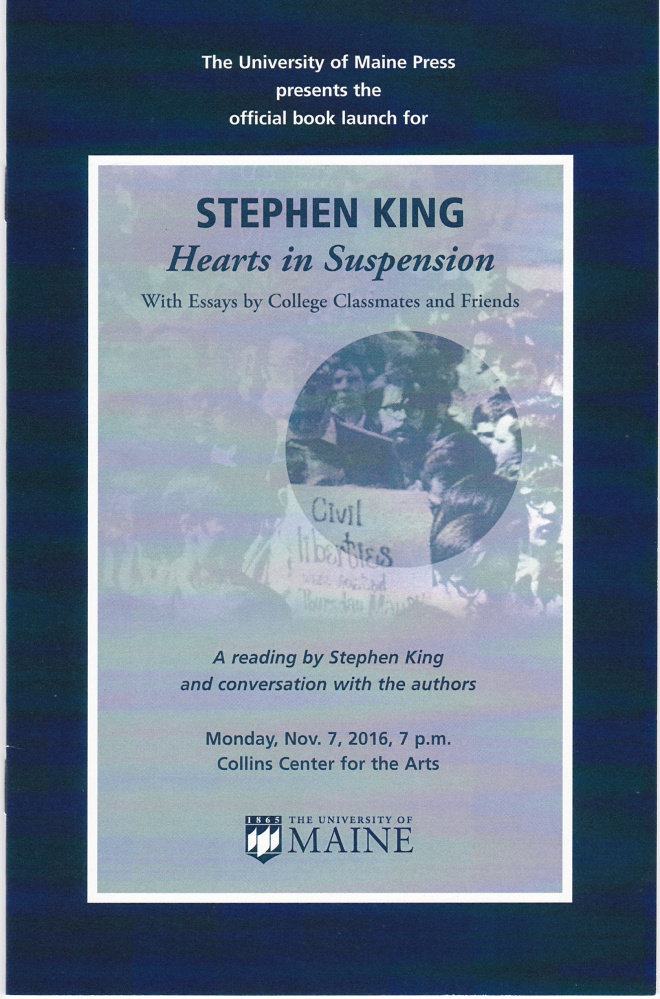

But luckily, some people do. And that brings us to the newest entry on the Stephen King bookshelf, “Hearts in Suspension,” which was launched in a presentation at the Collins Center in Orono on Monday evening. King was the marquee speaker at the event, but the book isn’t really about him. It’s about what the 1960s were like.

The idea for the book was generated by editor Jim Bishop and UMaine Press director Michael Alpert: How about a volume, they thought, that recounts the famous novelist’s formative UMO years, taking as its point of departure King’s 1999 novella “Hearts in Atlantis,” which is for all practical purposes a roman à clef about his freshman year on campus. Also included would be an essay by the master himself recalling his college days. Complementing the novella and recollection would be personal narratives by some of his friends and literary buddies, especially ones who participated in a legendary poetry-writing seminar in 1969 that not only boosted King’s writing momentum, but helped launch a number of writing lives — David Bright, Jim Smith, Sherry (Dresser) Dec, Diane McPherson, Bruce Holsapple, Keith Carreiro and more.

It all came together. And what formed was not so much the story of young Stephen King — though his fans will not be disappointed — but moreover, a heartfelt, accurate depiction of what it was like to be a college student in the late 1960s. The dumpy living quarters. The hydra-headed sense of alienation. The idealism (what is so funny about peace, love and understanding, anyway?). The stewing anger over governmental and social dishonesty and betrayal. The campus demonstrations, scuffles and stunts, like the “Great Chicken Crisis” inside the Memorial Union — hilarious yet, in its symbolism, deadly serious. The effects these tensions had on your studies, your ambitions, your family, the surreal dream that often passed for day-to-day college life. And looming like an inescapable shadow over everybody under 30 who could think in a straight line, war anxiety.

“If you were a male, 17 to 30 at that time,” writes Larry Moskowitz, “you organized your immediate life decisions in relationship to serving in the military and the potential of going to Vietnam and getting killed. It was ALWAYS on your mind, even if you didn’t go around talking about it constantly.”

Keith Carreiro tells the bizarre story of being drafted, reporting for the physical and then … being inexplicably turned loose. Diane McPherson, a member of the poetry seminar who went on to a literary career, recounts the “horsecrap rules” for freshmen, women in particular: “Wearing wheat jeans was forbidden (because) … from across campus wheat jeans looked like bare (white) skin; apparently the sight of a naked wheat-colored ass across the campus would excite the male students beyond control.”

Bruce Holsapple and Sherry Dec provide recollections of the poetry seminar run by Bishop and English professor Burton Hatlen that the participants (and others) still talk about nearly 50 years later (King describes it himself in his 2000 book “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft”). But more than the physical moment, they evoke the feel of the experience — what it was like to be young, smitten by poetry, writing and life: “I was now an English major, headed I didn’t know where,” Holsapple says, and proceeds to pull all kinds of strands together to illustrate the beginning of a consuming lifelong dedication to poetry.

Dec describes arriving on campus to find “intense conversations” going on all around her by people guided by “the ghost of President Kennedy’s voice.”

“Who was I in all of it,” she says, “and what was I supposed to do, once I knew?” She recounts a personal transformation spurred by the music (“The Doors, Beatles, Stones, Joni Mitchell, Janis”) and the writers — King, Holsapple, Bishop, Alpert, more.

And the striking thing about Dec’s testament, true to the 12 writers as well as King himself in this book, is the sense of the authenticity of the struggle, the desire to come face to face with the truth and tell it, whatever it turned out to be. Toward the end of Monday night’s closing question and answer period with the writers, Dec — wanting to make sure the point was not lost — said to the audience: This has been “the real thing” tonight, “not just about Stephen King,” but about the political and creative intensity of the UMO students of the late ’60s. “Sometimes the magic sticks around,” she said. Meaning, I took it, that Stephen King’s notorious truth-telling is just one outcome of a coalition (to use lifelong labor activist Frank Kadi’s word) of truth-seekers.

“Hearts in Suspension” is far more than an oddball work of literary biography. It’s a lens, crafted by people who were there, into a romanticized and fantasized, ridiculed and revised, almost forgotten, but critical turning point in American cultural history. If you want to know what the ’60s were really like, read this book.

Off Radar takes note of books with Maine connections every other week. His book “Summer to Fall” is available from North Country Press www.northcountrypress.com/summer-to-fall.html. Contact Dana Wilde at universe@dwildepress.net.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.