EAST DIXFIELD — In 1816, Allen Hall – one of the first settlers of Winthrop – moved to East Dixfield, where he bought 70 acres of land to farm.

Napoleon was still reeling from his defeat at Waterloo. Indiana had just become the 19th state. James Madison was president – the new country’s fourth one.

That was also the infamous “year without a summer” that followed the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia. The volcano messed with the Earth’s weather patterns, and snow fell all over New England in June. Many Maine farmers pulled up roots and headed west, worried that this strange new weather pattern might be permanent.

It might not have been the best time to think about starting a new farm – although, who knows, while Hall was eating the westward pioneers’ dust perhaps he purchased the land they left behind for a song. His gamble paid off.

Hall Farms, now being tended by the eighth generation of the Hall family, with the ninth generation waiting in the wings, celebrated its 200th anniversary this year. And it was named the 2016 Maine Dairy Farm of the Year by the New England Green Pastures Program.

Allen Hall probably never dreamed that his farm would grow over the next two centuries to 1,200 acres and do so much more than milk a handful of cows. Under the guidance of the current owners, Rodney and Randy Hall, and previous generations, the farm has added land, switched to organic dairy farming, expanded the barn (you can still see its 19th-century hand-hewn timbers) and built side businesses of beef cattle and maple syrup that are expanding every year.

That 200-year family legacy, 49-year-old Rod Hall says, has felt more like motivation than a burden.

“I don’t think that my brother and I have wanted to be the ones that let it fail,” he observed on a recent sunny winter day, when his 54-year-old brother was escorting an inspector around the farm. “I don’t think we ever wanted to be the ones that, all these generations did it and we got up some morning and sold it. There’s been a little more determination to make it a success because so many generations have worked hard to make it a success.”

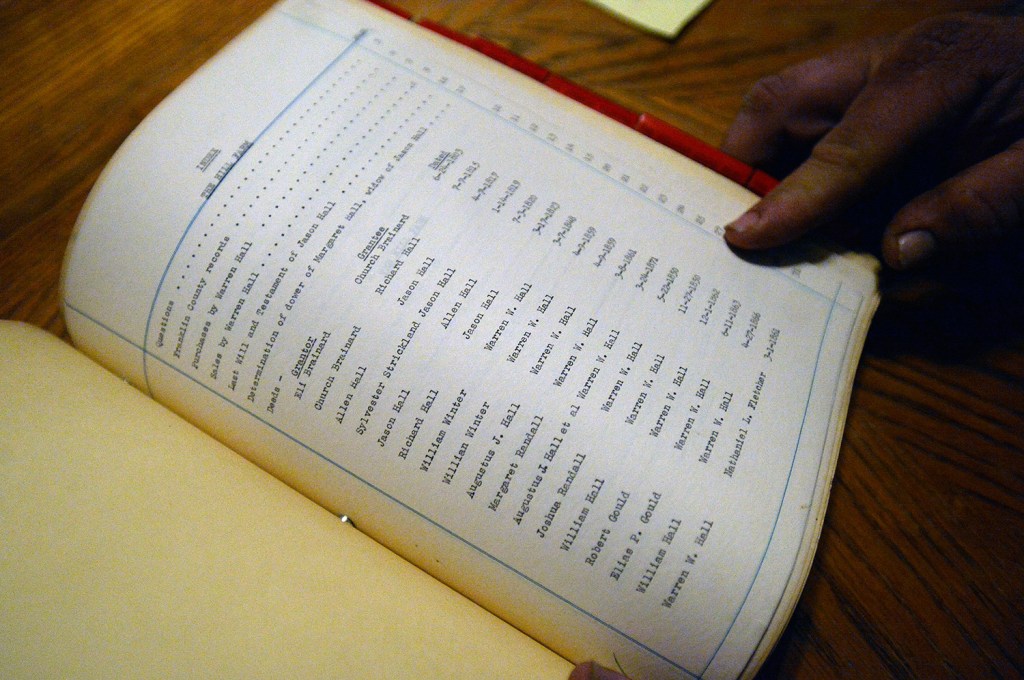

That determination to not lose the farm began with Allen Hall’s own family, with the help of the Wilton town selectmen. Old Kennebec County probate records show that in 1825 a judge in Hallowell granted a petition that declared Hall a “spendthrift,” whose lack of care handling money would soon “expose himself and his family to want.” The judge appointed a guardian over Hall’s estate.

After that initial bump in the road, subsequent generations shored up the farm by expanding it – but not too fast – and diversifying into areas that not only helped the farm survive but gave each succeeding generation a better quality of life.

They kept up with the times, whether that meant embracing mechanization in the 1930s, building a new compost barn in the 2000s, following the consumer trend toward local and organic food, or finding a way to milk the cows more efficiently. Like most dairy farmers, they carefully planned their spending on equipment and buildings.

Each generation trained the next, even while pushing the youngest Halls to always have a back-up plan – perhaps, in the long-run making it easier for them to commit themselves to the farm life, because they had other options.

No one knows how many Maine farms have remained in one family for 200 years or more. While other states have developed registries to keep track of such statistics, Maine has not, according to John Bott, director of communications for the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry.

DAIRY FARMS DISAPPEAR

The Hall farm probably didn’t start out as a dairy farm, but Rod Hall suspects his ancestor must have had at least one cow.

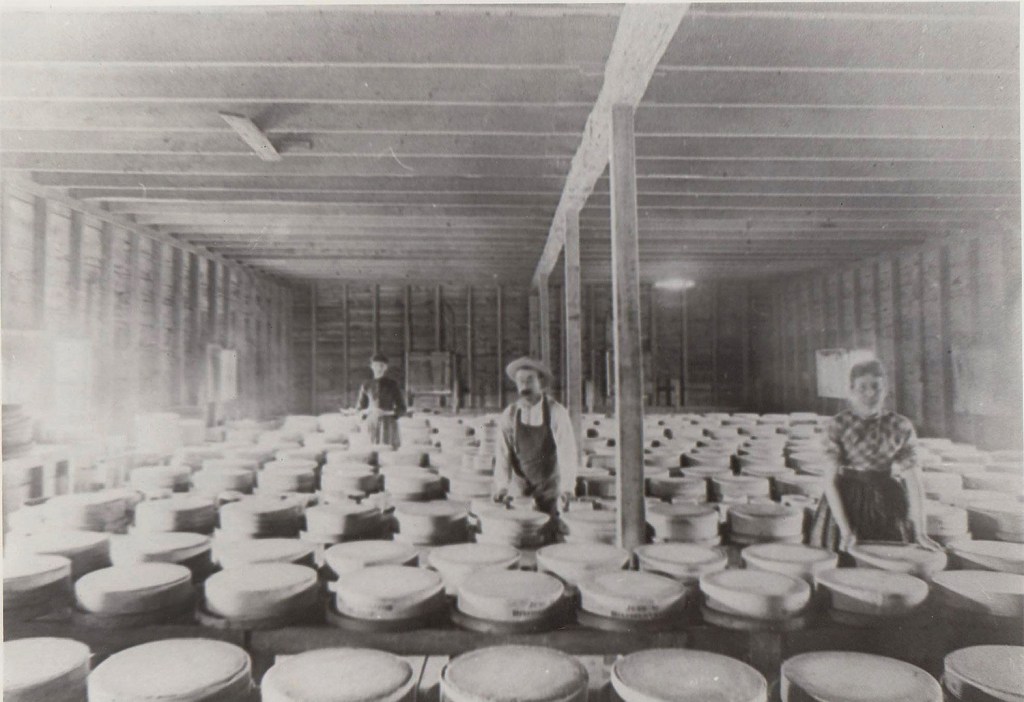

By the 1880s, local dairy farms were selling their milk to the Dixfield Centre Cheese Factory, and Hall believes his family’s farm was part of that group.

“From the stories that I’ve heard, there were always milk cows here,” he said in his classic Maine accent, “and like so many other farms in the state of Maine, they milked a handful of cows. If you had 10, you were big back then.”

When Rod Hall was born in 1967, there area was home to three dozen or so dairy farms. Today, there are three. Hall remembers a conversation he had with an inspector when he was a boy. The inspector said “You know, it will be a sad day when there are 1,000 dairy farms in the state of Maine.”

“There were 1,300 or 1,400 at the time,” Hall said. “Now there’s 250. Unfortunately, there is so much capital investment to buy a dairy farm. There’s three aspects of the farm you need, and people don’t realize that – you’ve got to have the cattle, you’ve got to have the buildings, and if you’re trying to grow your own feed you’ve got to have the land and the equipment. It’s not that it’s impossible, but it would take young people with a lot of determination and a lot of luck.”

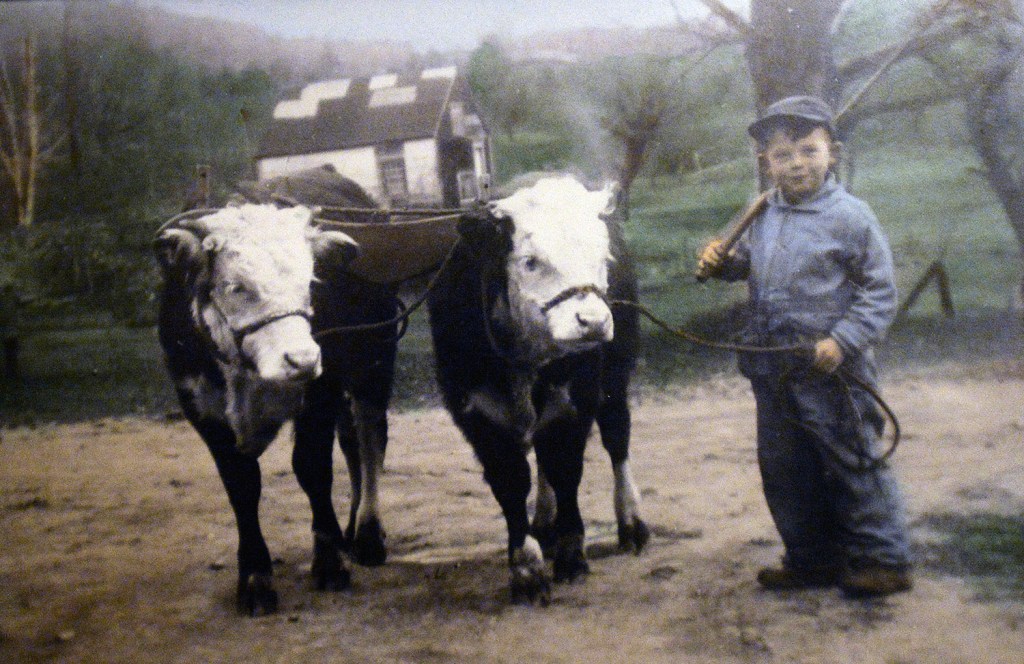

The farm – the mailing address is in East Dixfield, but the barn and two farmhouses sit in Wilton, Franklin County – was driven solely by horse-and oxen power until 1936, when the family, for the first time, bought a used tractor. The farm began milking registered Holsteins in 1945, and the Halls bought their first new tractor the following year.

When Hall was growing up, the family always milked 30 cows, but harvested a lot of timberland as well. The wood was sold to the local mills and to wood products companies such as Forster Manufacturing, which made toothpicks.

“My great grandfather (Ralph) always kept two pair of horses,” Hall said, “and of course they farmed with them in the summertime, but they were always working in the woods in the wintertime.”

During the dark days of farming in Maine, in the 1990s, when it seemed as if just about every farm was being sold off for development, Hall Farms was suffering, too.

“My dad and myself, we cut a lot of wood every winter to subsidize the farm, and that got to be discouraging,” Hall said. “We were cutting wood to support the cows.”

GOING ORGANIC AND DIVERSIFYING

By 2000, Dick Hall was beginning the process of transitioning the farm to his sons. Two years later, the family decided to make the farm an organic dairy farm. It was an economic decision. They knew, if they were going to survive, they’d have to either milk 500 cows and sell conventional milk, or milk 50 cows and sell organic milk.

“We knew we didn’t have land base enough to support 500 cows,” Hall said, “so we decided that, to stay small, we’d try to milk 50.”

They sell their milk to Organic Valley, and it’s used to make Stonyfield Farms yogurt.

During tough years, the Halls would delay buying needed equipment until the dairy economy improved. Just three months after the farm went organic, the farm was able to buy a new tractor.

Another thing that has helped the farm’s bottom line was the development of two sidelines. Each brother owns his own business, which helps to supplement his family’s income, so they aren’t entirely dependent on dairy.

Many Maine dairy farms have had to diversify in order to survive. Without the diversification, Hall said, “I don’t know that we would have gone out of business, but there would have been more challenges for sure.”

Randy Hall always had an interest in beef cattle and had a few growing up, so he expanded on that interest. About 12 years ago, he started a Belted Galloways breeding business. Today he sells semen and embryos as far away as South America.

Rod Hall has had a maple syrup business since high school. In 1986, the first year he tapped commercially, he had 386 taps on the family farm. Next year, with the help of his 17-year-old son, Caleb, Hall hopes to have 6,500 taps. His goals are to have 10,000 taps by 2019 and a new sugarhouse by 2020 or 2021.

Now, 200 years after Allen Hall first set foot on this soil, the heart of the family farm – where the barn and farmhouses lie – has expanded to about 500 acres. There are 400 acres of woodlands across the road, and the rest is scattered around here and there.

LAND ADDED BIT BY BIT

“If there’s a piece of land that becomes available and it fits in good for us, we try to buy it if we can,” Hall said.

The farm has acquired land in a variety of ways, as Hall learned growing up, listening to stories around the supper table. His great-grandfather once traded a cow for a small piece of land. And the family acquired a field across the road from a Dr. White, the local physician. As he got older, White didn’t like to drive at night, so if he had a nighttime emergency to attend to he would call Ralph Hall (Rod’s great-grandfather), who would take him to his house call.

Whether it was by purchase or gift, no one knows, but the Hall family ended up with Dr. White’s parcel of land.

Rod Hall estimates that, since 2001, the family has invested $300,000 to $400,000 into the farm in capital improvements and buildings.

In 2013, they added a compost barn filled with a bed of shavings for the cows that is tended to every day. The bedding steams and keeps them warm and comfortable.

“The cows just love it,” Hall said.

The compost barn was one of the things that caught the attention of the New England Green Pastures Program.

Dairy farms recognized by the Green Pastures Program are chosen for their production records, environmental practices and herd, pasture and crop management, as well as overall excellence.

Gary Anderson, an animal and bioscience specialist with the University of Maine Cooperative Extension, says the Halls have “a cohesive multi-generational farm that works well together.”

He also cited the new compost barn that lends itself to “cow comfort,” as well as the high-quality organic corn silage and organic grass forage the farm produces.

ONE WHO WANTS TO FARM

What the future holds for Hall Farms will likely be up to Caleb Hall, who is the captain of the football team at Mount Blue High School and will graduate in the spring. So far, at least, he’s the only member of the ninth generation of Halls who is interested in farming. (Randy Hall’s daughter is going to vet school, and Rod Hall’s daughter is in Scotland, studying for her doctorate in international relations.)

Just like his father, Caleb Hall has had no doubt about living the life of a dairy farmer.

“I just don’t know any different, and you learn to love what you do,” he said. “That’s the way I look at it.”

Now that he’s a senior, Caleb comes home early from school every other day, often bringing a few friends with him. They grab a bite of lunch, then head out into the woods to tap more maple trees, inching closer every day to that goal of 10,000 taps. The teenager knows that he would like to keep expanding the farm and has a lot of ideas about how to run things differently. He knows it won’t be easy.

“If I’m the only one taking it on, its going to be a lot harder,” he said.

When Rod and Randy Hall were Caleb’s age, they both wanted to farm, too, but their father told them they had to go to school first so they’d have a back-up plan for supporting their families. Randy got a four-year degree from the University of New Hampshire, and Rod got a two-year associate’s degree from the University of Maine.

Rod Hall says “the hardest thing was for me to go away to college,” but now that’s exactly what he’s asking his son to do as well.

Caleb Hall will study fire science and get paramedic training at Southern Maine Community College. But make no mistake – he’ll be coming back to the farm. “If I didn’t love what I do, I wouldn’t do it,” he said.

Rod Hall said he thinks one reason his son is so interested in farming is that he has seen previous generations always investing in the farm, never selling off pieces to pay the bills or buy something they want.

He hopes his son will carry on that tradition.

“No one knows what the future is going to hold,” he said, “but right now the future looks good.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.