CHELSEA — When Marjorie and Randall Albert decided to put an addition on their home, they contacted a contractor they knew and who had done work for them before.

With budget in mind, they decided if a contractor could pour the foundation and frame and enclose the walls, they would finish the interior.

But four and a half months after signing a contract for what they were told would be a three-week project, they don’t have the room, they don’t have the $16,000 they spent so far to have it built, and they don’t really have many options.

Over the weekend, Randall Albert was planning to start tearing it down and salvaging the framing lumber. After that, the Alberts will have to deal with the addition’s foundation, which other contractors have told them must be removed because it could heave and damage their existing foundation.

Contractor Tim Moody, whose company T & L Construction was hired to do the job, said the Alberts made a number of changes over the course of the project. They were, he said, difficult to please, and they are now complaining about work they accepted.

“This project became very ambiguous with the changes,” Moody said. “It should have been a simple addition, but there’s been a lot of animosity.”

THE DISPUTE

“It’s three walls and a roof,” Randall Albert said. “How hard could it be?”

The Alberts, Randall, 50, and Marjorie, 46, sat last week at the kitchen table in their home in southeast Chelsea, not far from the Whitefield line, and talked about what they wanted.

When they bought the house 21 years ago, it was the perfect size for their young family, but as they grew up, the Alberts wanted more space.

“His family all lives here,” Marjorie Albert said, circling her hand in the air. When the extended family gets together for holidays and other events, it’s a houseful. As many as 20 relatives might fill the rooms. Their daughters are grown now, and they want to have room for grandchildren. And as family members age — parents and grandparents — they are less able to negotiate the stairs to get to the kitchen and dining room on the home’s upper floor.

“I am really big on Christmas,” Marjorie Albert said. “I want a full-size tree.”

That means a 16-foot tree, the size she grew up with, Randall Albert said.

The addition they hoped for would be built at the ground level on the front of the house, creating a great room. At most, it would be 20 feet by 24 feet, with an open ceiling and exposed beams. They had already bought a new front door, and they planned to move windows from the existing front of the house into the addition. They wanted a gable end on the roof, and they pictured two triangular windows set into the peak of the gable to let in light. Those would have be custom-ordered.

They were refinancing their home to pay for the work. When they were ready to talk to a contractor, they thought of Moody, who had done earth work for them and put in a new driveway.

“We saw him around, in the IGA, and we’d say hello,” Marjorie Albert said.

Randall Albert said Moody offered up some ideas and suggested building a larger addition, 24 feet by 32 feet. It would just about double the footprint of their home.

On Aug. 23, the Alberts signed the contract Moody drafted. When Moody told them he’d need a check for $750 for the building permit, they gave him one that day.

The building permit, which cost $101.80, was issued the next day.

Moody’s contract listed the cost as $19,000 and required an upfront payment of $6,333, which they paid, and they made regular payments after that for labor and materials that Moody bought for the job. To date, they say they have paid more than $16,000.

After weeks of waiting for work to start, they had concerns over what was being done from the start. The frost wall was uneven and bowed. When the framing started, the Alberts noted that in a number of places the studs didn’t touch the top plate. They also kept track of days the crew worked, and there were weeks when no work was done.

During construction, they asked Moody what the pitch or angle of the roof would be because they wanted to order the windows.

“Tim told us he wouldn’t know what the pitch would be until they were done building,” Randall Albert said.

When it became clear that the gable end wouldn’t work out, the Alberts said they agreed to change the roof to a shed style roof with no gable.

Moody and his crew changed the framing, but they still had concerns.

“I took a couple of drafting classes in high school, and I thought maybe I should draw a picture of what we wanted,” Randall Albert said. “But he’s the contractor. He should know what he’s doing.”

Moody, who has about three decades of experience, said his company writes contracts based on what the customer wants.

Reached at his home in Pittston last week, he said in this case, he’s not sure what the Alberts wanted because they had no plans.

“We do lots of buildings and additions and garages that have no plans whatsoever,” he said.

Moody asked for plans repeatedly, he said. But even with no plans, his crew poured concrete for the footers and frost wall, and started framing the side walls.

When the Alberts asked, he said his crew cut off the top of the walls to suit the new design. But still, he said, although he asked, the Alberts gave him no plans.

“The beauty of it is that the lumber companies will do the drawings for you if you use their materials,” he said, and those drawings are enough for carpenters to work from.

He said the roof was changed to a shed-style roof and then changed again, and the Alberts wanted radiant floor heating added, which he agreed to do for $1,000.

As the project changed, he didn’t ask for change orders, nor did the Alberts give him any.

“I’ve been at this for 30 years,” Moody said. “I’ve been at it long enough to know some common sense. You need to be able to work with common sense and work with customers that allow you to complete a job. It doesn’t matter who they are.”

He said he offered to come back and fix things, but he wasn’t allowed to do that.

“I don’t have a problem with the work we did,” he said. “Absolutely it would be the kind of work I would do on my own house.”

CONSUMER PROTECTION

In Maine, it’s very much a case of “buyer beware.”

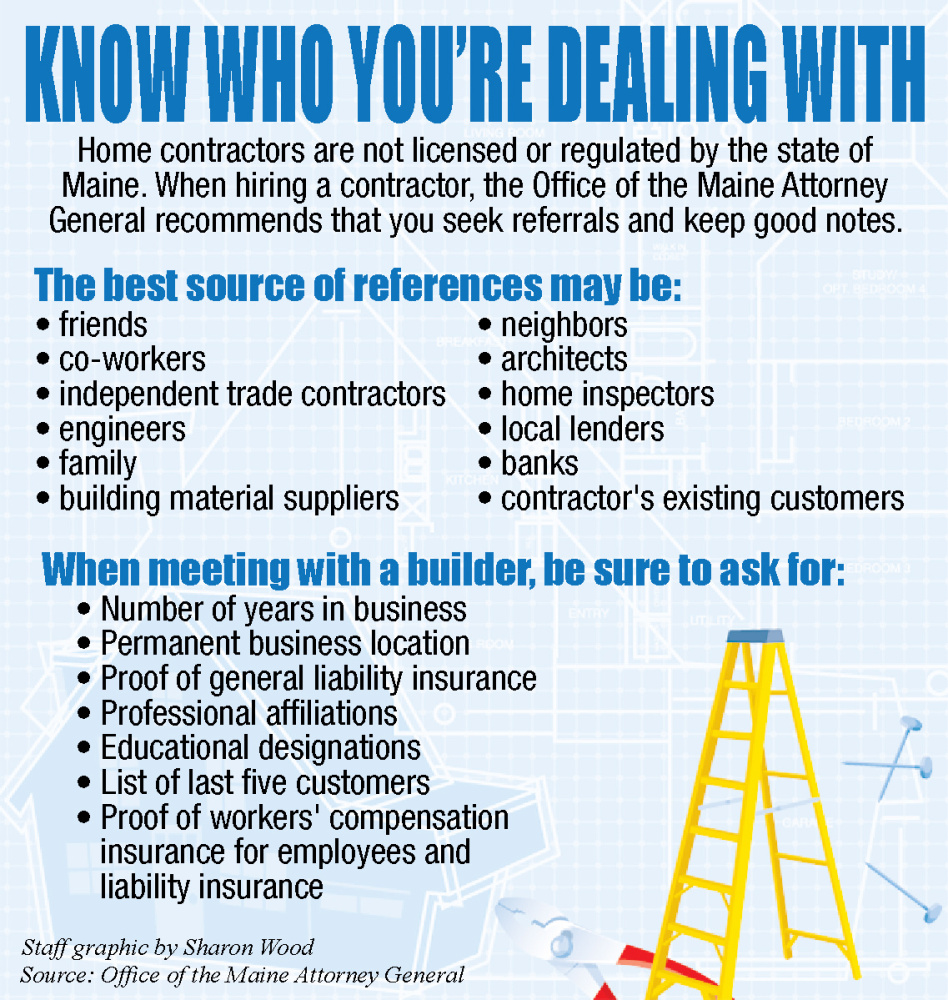

Martha Currier suggests that people who are planning home renovations and additions contact the state Attorney General’s Office, where she is the complaint examiner in the Consumer Protection Division.

The Attorney General’s website offers up model contract and change order documents for contractors to use and a warning statement that contractors are required to provide for projects costing more than $3,000.

“You have to stick to the contract,” Currier said. “And make sure you get changes in writing. People often get taken with that. The more you cover yourself with a paper trail, the better.”

The Alberts tried.

The Attorney General doesn’t have the staff to take contractors to court, but Currier said filing complaints helps. If a pattern of behavior emerges, that can trigger the start of an investigation.

On Nov. 19, the Alberts spelled out via a letter the extent of their dissatisfaction with Moody’s work. They found, among other things, that the foundation didn’t extend below the frost level along the front of the addition; the total height of the wall was 22 inches. The concrete wasn’t sufficiently tarred to create a moisture barrier, the height of the walls wasn’t level, and there was no indication the frost wall was connected to the existing foundation. They also listed examples of where the framing was problematic: Some of the 2-by-6 framing boards didn’t touch the top plate, the plywood was not adequately attached to the studs and Moody’s recommendation for support beams on the rafters would not be adequate to handle the snow load.

They asked Moody to find a subcontractor to complete the project and to pay for all the required materials to complete it. They asked him to pull out the foundation his crew put in and to put in a new one. And when the job was complete, they would give him the final payment.

And that’s where the project sits now, nearly two months later.

They say Moody never asked for plans.

“Even if we did have plans and changed them,” Marjorie Albert said, “the foundation was incorrect.”

Since work stopped, the Alberts have explored what options are open to them.

They asked other contractors to look at the work, and they were told that the walls of the unfinished structure were unbraced, of poor quality and could blow over in a strong wind, which could damage their house. The foundation could also damage their home if it were to heave. One contractor estimated the cost to remove what was there and give them what they wanted at $28,000.

The Alberts consulted an attorney, who reviewed their case, but didn’t take it.

Andrew Dawson, who practices in Augusta, told them even if they were to win a judgment against Moody in court, they might never be able to collect what was owed.

“Ultimately, my concern is that I don’t want to take a case and cost you money that you will never see again,” he wrote to them. “You will find this is a common theme in a lot of consumer complaints, and one for which I don’t have a good answer. I just can’t, in good conscience, be the last in a line of people to take your money without you receiving a meaningful result.”

They filed a claim with their insurance company.

At the end of December, they received notification their claim was denied. “We have determined your contractor failed to properly construct your addition,” read the letter from National General insurance company. “Regrettably, your policy language does not cover damage caused by poor workmanship.”

The Alberts also sought help from the attorney general’s office, although initially, they were unaware of the resources there. Marjorie Albert filled out a complaint for and sought mediation. Mediation is voluntary, and they are waiting to hear.

They have taken their case to Facebook, where they have posted photos and their story.

Moody said he’s aware they have done that, although he has not read what they wrote.

At the request of the Kennebec Journal, Richard Dolby reviewed the contract the Alberts had with Moody, as well as photos of the construction.

For 23 years, Dolby worked as the director of code enforcement for the city of Augusta. He was the acting director of Building Codes and Standards for the state of Maine and worked with the team that adopted the Maine Universal Building and Energy Code, which governs building standards in Maine for cities and towns with populations of 4,000 or more. He now has his own business offering inspection services and works part time as code enforcement officer for Vassalboro.

Maine does not license contractors other than plumbers and electricians, he said, and Chelsea, like many towns with populations smaller than 4,000, doesn’t have a building code. If there is no code, he said, there’s no standard to hold a contractor to.

“There is such a thing as professional standards, and a good contractor would follow them,” he said.

While the Alberts should have provided drawings, their contractor should have been able to build a frost wall without plans.

Moody’s contract, he said, has several features that the attorney general’s office asked for, including the price of the work and the starting date, but it omits others, like specifications for the work to be done. Other than the frost wall, the contract contains no specifications.

The contract also offers no warranty.

“I have seen walls that have been poured that were not absolutely straight, and you could still get a wall up,” he said.

But, he said, the guidance from the Attorney General’s Office requires written change orders, and there were none.

And while lumber companies offer many services, drawing up plans isn’t one of them.

“Lumber yards do a lot of drafting if you buy your lumber from them,” Dolby said. ” But they will have written all over them: ‘Not for Construction.’ They are not designing your house; they are drawing an illustration for what you want.”

As unfortunate as the Alberts’ situation is, he said, there are 999 out there that are worse.

“This is a far more common occurrence than you or I would like to believe,” he said.

CONTINUING CONFLICT

At this point, there is little that Moody and the Alberts agree on.

On Thursday, Marjorie Albert found herself at the Kennebec County Sheriff’s office, looking for someone to serve a complaint.

On Nov. 11, a stanchion that Moody’s crew had built to lift the power lines to the house out of the way of the work going on came down on the back of her car.

She’s taking Moody to small claims court to recoup the $778.35 she spent to repair the damage.

The Alberts said Moody said he would pay for the damage, so they got an estimate from Concept Auto/Emerald City Tire. They offered to get a second estimate, but he didn’t ask for one.

Body shop owner Dale Green said Friday Moody had given verbal authorization by phone to do the work.

“He agreed to pay and told me to send him the bill,” Green said.

When the work was done, which Green characterized as cosmetic, he called Moody several times, but got no response.

During the Thanksgiving weekend, he drove to Moody’s home with the bill.

“He told me I was out of luck,”Green said. “His wife had gone shopping and she had the checkbook.”

He interpreted it as stonewalling, and in the end Marjorie Albert paid the bill to get her car back.

Moody denies he ever gave authorization for the work and said he saw the estimate a day after Green showed up at his door.

“Did they say Randy (Randall Albert) used to work there?” Moody said. “What kind of estimate do you think that was?”

Randall Albert said in fact he did work there, and he believes Green gave him a break on cost.

They even dispute something as small as paperwork.

Moody said when he asked for $750 for the building permit, which cost $101.80, the balance of the money was to cover the cost of labor and time to fill out the paperwork.

“They didn’t do any of the paperwork,” he said.

Marjorie Albert said she filled out the application, based on what Moody told her, and it’s clearly her handwriting on the application.

The Alberts acknowledge they made many mistakes that will cost them a lot of money. While they are private people, they wanted to help others.

“We didn’t know what else to do,” she said.

Jessica Lowell — 621-5632

Twitter: @JLowellKJ

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.