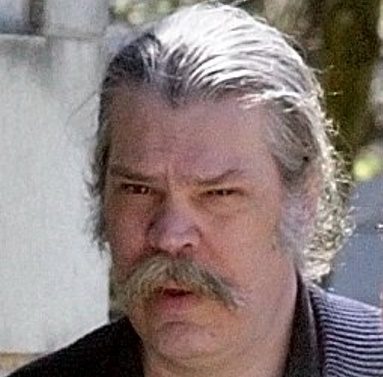

Mark Bechard, who stabbed, beat and stomped four nuns after forcing his way into a Waterville chapel in 1996, killing two of them and injuring two others while in the throes of severe mental illness, has died.

Bechard, 58, died at 11 a.m. Sunday at Hawthorne House, a nursing home and rehabilitation facility, in Freeport, according to a letter from the state Department of Health and Human Services on file at the Capital Judicial Center in Augusta.

Bechard had been found not criminally responsible for the murders and placed in the custody of the DHHS commissioner.

He spent years in the state’s forensic hospitals and most recently had been living in the community under the supervision of Riverview Psychiatric Center’s Outpatient Services team.

The letter to the court from Kelly Stewart, acting program director of Riverview Psychiatric Center Outpatient Services, says Bechard “had been diagnosed with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a progressive neurodegenerative disorder also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, characterized by progressive muscle weakness) and recently had experienced steady decline in his respiratory function. His passing was reported to be peaceful.”

It also says he had prepared a will with help from attorney Stephen O’Donnell and that Bechard’s body was sent to a Belfast funeral home to be cremated. The DHHS letter was sent to the clerk of courts in Augusta as well as Bechard’s attorney, Harold Hainke; Assistant Attorney General Laura Yustak; and Ann LeBlanc, director of the State Forensic Service.

Bechard was committed to a state psychiatric hospital in October 1996 after he was found not criminally responsible, by reason of mental disease or defect, on two counts of murder for the Jan. 27, 1996, incident at Servants of the Blessed Sacrament chapel in Waterville.

Authorities said Bechard, 37 at the time, was suffering a psychotic episode when he entered through the chapel and attacked four nuns, killing Mother Superior Edna Mary Cardozo and Sister Marie Julien Fortin.

Sister Patricia Ann Keane survived the attack but died later from her injuries. Sister Mary Anna DiGiacomo, who was paralyzed on her right side, died in 2006.

In June 2016, Bechardasked the courts to allow him to move from a group home on Glenridge Drive in Augusta to a 10-unit apartment building on Commercial Street where residents are supervised by at least two people at all times. Justice Robert Mullen denied the request, writing in his decision that he shared concerns expressed by the director of the State Forensic Service that Bechard needed consistent treatment for his mental illness.

Mullen said he could not look past concerns about the lack of stability of Bechard’s treatment team, especially during the proposed transition to new housing, which could increase Bechard’s anxiety and could result in a possible “decrease in the predictability of psychiatric stability” in him.

Mullen wrote it was impossible for him “to recall a more horrific set of circumstances than those that occurred on Jan. 27, 1996 in Waterville, Maine. They cannot, and will not, ever be forgotten.”

O’Donnell, Bechard’s personal attorney, said he first met Bechard when Bechard was living in the community.

“I never knew him when he was actively mentally ill,” O’Donnell said Tuesday from his Augusta office. “He was just a very pleasant person to interact with. He’s probably representative of a lot of folks who have mental illness who become psychotic and when provided appropriate treatment can live a normal life.”

O’Donnell said Bechard was a private person who was interested in books and music and who didn’t like a lot of publicity.

O’Donnell said he represented Bechard and other people who had been found not guilty by reason of insanity in a successful effort to get Social Security benefits restored so they could support themselves while living in the community.

While their mental illness qualified them for the benefits, the payments were suspended while they were living in a public institution and the issue revolved around whether halfway houses and supervised apartments were considered part of the institution.

O’Donnell also said he has spoken to Bechard’s mother over the years. A message left at her Waterville home Tuesday afternoon was not returned immediately.

“His mother has told me a number of times they (Bechard’s partents) made a number of efforts to get him help” before the tragedy at the chapel.

Bechard had stopped taking his anti-psychotic medication and his parents called a state hot line when they saw his behavior becoming more erratic. Because of a power outage, the message never made it to the community mental health center that was treating him.

Testifying for the defense at her son’s trial, Diane Bechard said she made seven calls to try to get help for her son after seeing him outside his apartment and realizing he was losing control. He was speaking in incomprehensible syllables.

He had been admitted to the Augusta Mental Health Institute — Riverview’s predecessor — nine times before the nuns were killed.

At the conclusion of a nonjury trial held in Somerset County, then-Superior Court Justice Donald Alexander found that Bechard was not criminally responsible for his actions.

“There’s no significant doubt that at the time of the criminal conduct on Jan. 27, Mark Bechard lacked substantial mental capacity,” Alexander said, according to published reports at the time. “He had no relation to reality at all. He had no capacity to appreciate his conduct or its impact. Whatever his mind was telling him in his delusions as he moved about the chapel and convent, it was to destroy and kill whatever came in his path.”

The nuns publicly forgave Bechard and continued to pray for him.

Records at the court show that Bechard’s mental condition began to improve about 2002 when he began to take an active role in therapy, and he was first allowed to leave hospital grounds — under supervision — in a court order dated July 2003. He moved to a group home in the community in 2012.

Bechard’s parents became facilitators of the NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) Mid Maine Support group for several years.

When he became commissioner of the Maine Department of Public Safety in 2011, John Morris said the slaying of the nuns in Waterville — where he was police chief — was the impetus for him to start “the Midnight Team,” a group of mental health crisis counselors who ride with police from 6 p.m. to 2 a.m. to help address a variety of problems, including contact with people with mental illness.

Attorney Harold Hainke represented Bechard when he petitioned the court for modifications in his treatment program — including living conditions and unsupervised time in the community.

“There was such huge publicity connected with his petitions, he was always very reluctant to petition,” Hainke said Tuesday. “He was just a nice guy whose mental illness was pretty well controlled with medication but just his crime was so horrific — and rightly so — it was held against him.”

Hainke said he had sought and received permission from the court several months ago to allow Bechard to live full time at the nursing home.

Hainke added, “From the day I met him and from everybody I spoke to about him, he was always a very peaceful, cooperative person.”

Betty Adams — 621-5631

Twitter: @betadams

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.