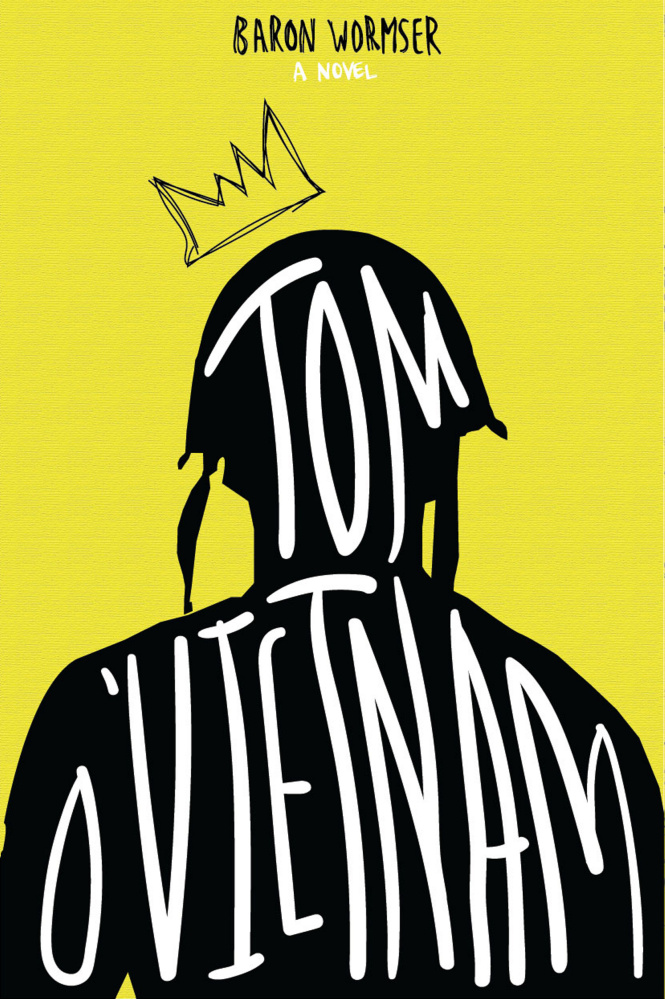

“Tom O’Vietnam”

By Baron Wormser

New Rivers Press, Moorhead, Minnesota, 2017

164 pages, paperback, $19

About once a year, I get out the DVD of James Earl Jones playing Shakespeare’s King Lear and watch it. Sometimes I also listen to another audio production of the play. Lately I have quit watching or listening in the final act because I can’t take it. The ending is more painful to me now than it ever was.

To get the most out of Baron Wormser’s new novel, “Tom O’Vietnam,” you need this close an intimacy with “King Lear,” I’m afraid. The main character is so bound up with the play’s events and language, both literally and figuratively, that much of what goes on will be lost otherwise. Brief summaries of the book and the play might be enough to launch you into this remarkable novel.

The book’s main character is a Vietnam War veteran in his early 30s named Tom. His life is at loose ends because he is suffering from some version of PTSD. Several horrific war scenes haunt him, and he can’t lay them to rest. He has no home, and the novel follows him on bus trips to visit his sisters, an on-again off-again girlfriend, and a Shakespeare professor with whom he has built an extensive correspondence, including frequent phone calls, to discuss the play “King Lear.” He is trying to figure out what the play means and why he has been obsessed with it since he carried a paperback copy of it all through the war. Those are the bare bones of the book.

The play is about an old king, Lear, who wants to retire and divide his kingdom up between his three daughters. In one of the most head-scratching scenes in all of literature, he requires each daughter to tell him how much she loves him. Two of the daughters butter him up sickeningly, but the third daughter, Cordelia, tells the unvarnished truth — which is not negative but not flattering. Lear blows his top, and Cordelia flees to France. When a loyal courtier objects to Cordelia’s treatment, Lear banishes him, too. So right away, we know Lear is off his rails.

Meanwhile, another courtier, the Duke of Gloucester, is deceived by his bastard son, Edmund, into thinking his legitimate son, Edgar, is plotting to kill him. So Edgar is forced by circumstances into hiding and disguises himself as a lunatic named Tom O’Bedlam.

The two treacherous daughters immediately turn on their old father, and he is devastated by their betrayal — “you unnatural hags,” he says. They hatch further political treacheries, which Edmund turns against them, and as a result the Duke of Gloucester is horribly tortured and maimed. With Lear gone in power and mind, the kingdom is destabilized, and the result is war.

In the end, just about everybody dies amid nearly intolerable irony. But this ending is not like the ending of, for example Hamlet, where the mass death, as terrible as it is, at least has recognizable currents of motivation. In Lear, everything from family relations to political power balances to the conditions of aging and death has gone completely off the rails. The bad guys are mad. The good guys are all sorts of mad. The end is mad. I have never felt such pain anywhere else in literature.

In the play, Edgar copes with terribly twisted circumstances by feigning madness and taking on the disguise of Tom O’Bedlam. In the novel, the war veteran Tom is coping with his psychological circumstances by taking on a kind of cracked persona of himself — Tom O’Vietnam. Lines from the play surface on practically every page, evoking the different layers and complexities of suffering that harrows Tom’s life as a combat veteran. His sisters are sympathetic and want to help him, but they’re skeptical, and they wish he’d give up his obsession with Lear. Tom refers frequently to an African-American war buddy, Knightley, whose wise-cracking “wisdom” helped Tom cope with the madness of war. Tom goes to visit him, too, with heartbreaking results.

The book is an arresting psychological portrait of one of the effects of a mad moment in America. To understand it, you need a basic knowledge of Shakespeare’s play. A familiarity with the films “Apocalypse Now” and “The Deer Hunter” and Tim O’Brien’s book “The Things They Carried” wouldn’t hurt, either; nor would an attentive watching of the recent PBS documentary series “The Vietnam War.” If you share a certain angst about what happened to a generation of American troops, the background work will be well worth the trouble to gain full access to this perceptive, heartfelt, well-written book.

Baron Wormser, now of Vermont, lived for decades in western Maine and was the state’s poet laureate from 2000-2005, receiving an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from UMaine Augusta in 2005. He is the author of nine collections of poetry and several books of prose, including “The Road Washes Out in Spring,” a reflection on life in the Maine backwoods. “Tom O’Vietnam” is available through his website baronwormser.com/books/tom.html and online book sellers.

Off Radar takes note of poetry and books with Maine connections the first Thursday of each month. Contact Dana Wilde at universe@dwildepress.net.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.