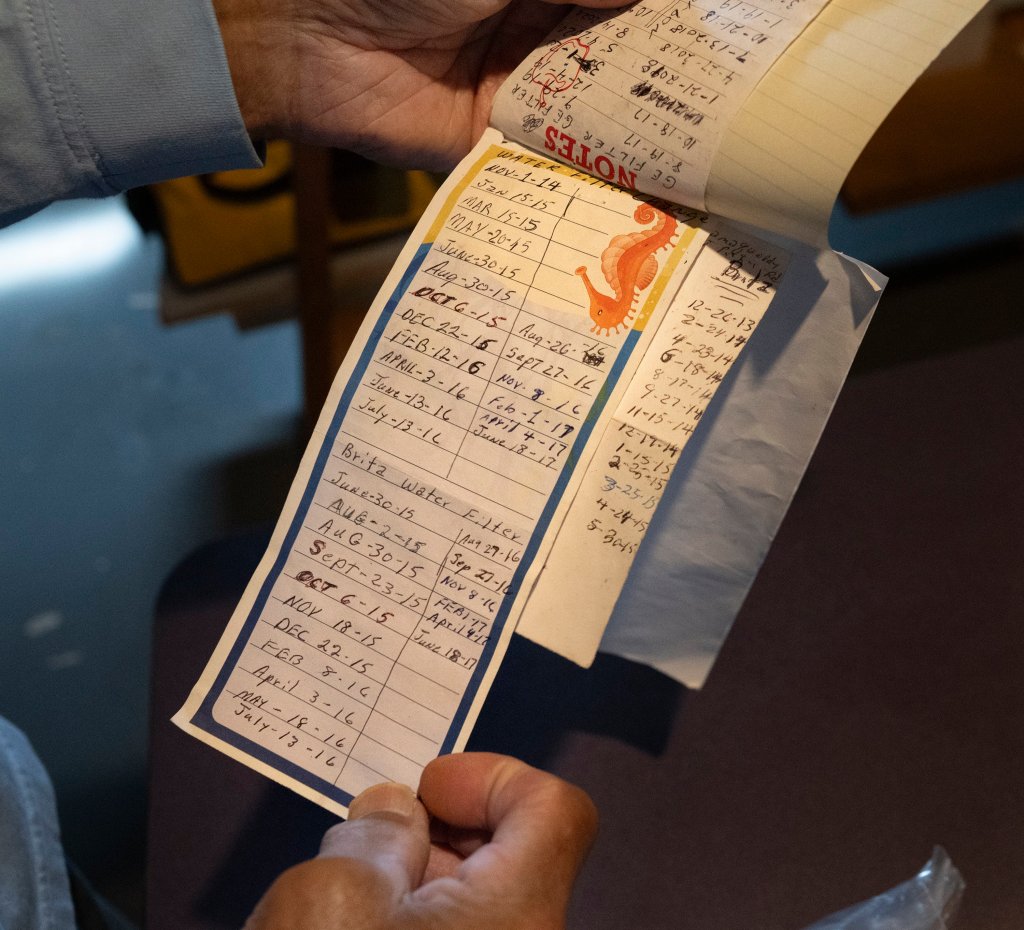

SIPAYIK — At 83, Tom Bassett is nimble as he makes his way down a steep flight of basement steps. Nestled in the rafters, his 5-micron filter intercepts incoming tap water from the main line.

In neat, cursive columns, he tracks every time he’s changed it since 2009.

Sometimes he changes it every month. Other times, every three months. Never more than six. Even with the filtration system, Bassett doesn’t drink his tap water. He uses it strictly for laundry and the dishwasher.

“Basically that’s it. The rest of it we buy,” he said.

For decades, the water flowing into the 230 homes on the Passamaquoddy Reservation at Pleasant Point (Sipayik) was rarely safe to drink. That has fluctuated over the years. These days, contaminants only surpass recommended levels once or twice each year.

Still, that history and inconsistency means few trust the water, and efforts to develop a reliable new source have progressed slowly.

PROBLEMS AT THE HEADWATERS

Brianna “Sipsis” Smith recalls several years ago when her daughter at age 4 ran herself a bath.

“Get out,” Smith told her.

“Why?” her daughter asked.

“Look at the water,” Smith replied, pointing to the brown tub and the silt.

“It’s always like that,” her daughter said.

Like most people on the Passamaquoddy Reservation, Smith is cautious with the tap water.

“I don’t even give my dog the water,” she said.

To find the source of Sipayik’s water quality problems, one must go upstream.

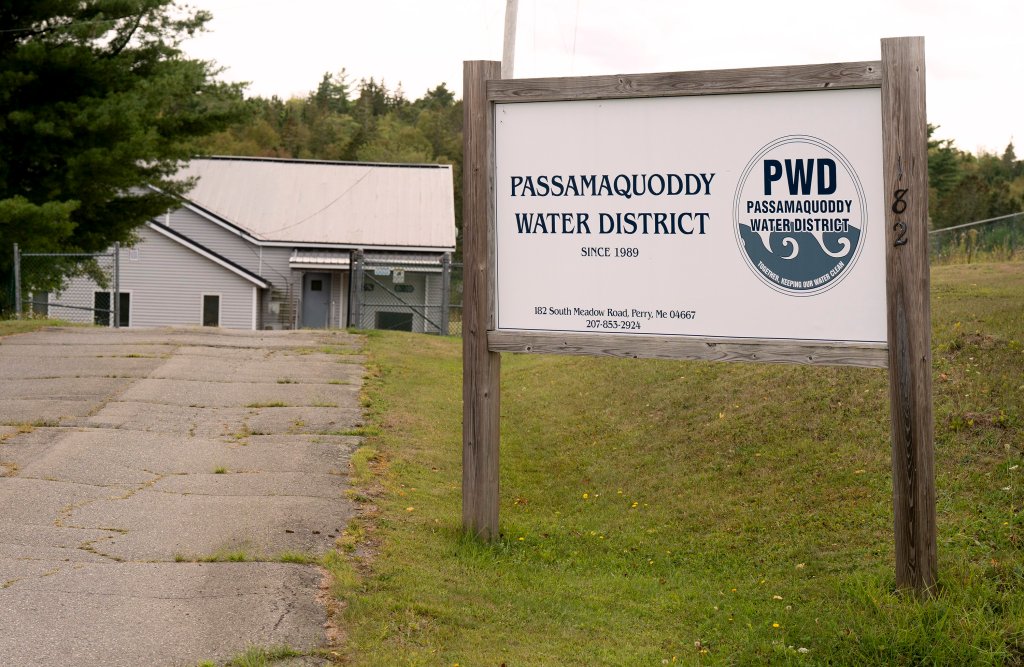

The Passamaquoddy Water District — a quasi-municipal nonprofit corporation that delivers water to the reservation and the town of Eastport — draws from Boyden Lake, in Perry.

Water there is subject to the extremes of the natural environment. Surges in rainfall, periods of drought or even beaver dams can cause large fluctuations in organic material such as decaying vegetation, which can discolor the tap water.

It can also cause the saturation of a group of chemical compounds known as Total Trihalomethanes (TTHMs) to spike. The compounds are produced by the interaction of chlorine, used for water treatment, and organic material in the water. They are regulated under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s clean drinking water standards, and long-term exposure is connected to an increased risk of cancer and problems with internal organs and the central nervous system.

Once or twice per year, the contaminant levels in Sipayik’s water rise above the federal allowable standard, according to data provided by the tribe’s environmental department. They are almost always elevated. Most recently, treatment biproduct levels on Dec. 5, 2024, jumped to over 120 parts per million (ppm) at one test site — a 50% exceedance of the federal limit of 80 ppm.

In October 2022, the Passamaquoddy Water District installed a granular activated carbon filter in its system to remove organic material before treatment. That has helped somewhat, said William Longfellow, the tribe’s water quality program manager and one of it’s three representatives on the district board.

But actual improvements in water quality can only do so much.

“The erosion of trust is pretty far gone,” he said.

A MATTER OF TRUST

For over a decade, the tribe has tried to develop a reliable source of water for the reservation. It has done so with limited support from the city of Eastport, where many people have private wells, or access to federal support.

In 2014, the tribe stress-tested a well on property it owned within the town of Perry, with which it shares a border. Those tests drained several nearby wells, angering the residents who owned them.

The tribe “made it right,” according to the tribe’s Director of Planning and Resilience Bob Wood, but residents of Perry were not pleased. Voters there tried to constrain the tribe’s activity with an ordinance, which passed overwhelmingly, to regulate large-scale water extraction. The ordinance was widely interpreted to be directed at the tribe, including by a Perry resident who told the state Legislature it was “to prevent anyone from doing this type of activity in the town again without the knowledge and consent of the Town.”

The testing and studies mandated by the ordinance would cost the tribe hundreds of thousands of dollars, Chief Amkuwiposohehs “Pos” Bassett estimated. So the tribe successfully led an effort to change state law.

LD 906, introduced to the Legislature by then-Passamaquoddy Rep. Rena Newell and signed in 2022, made changes to the Maine Indian Settlement Implementing Act allowing the tribe to place the land in Perry into trust with the federal government without the town’s approval. Once in trust, the tribe can take advantage of federal programs that support the maintenance of clean drinking water.

For Perry and the reservation community, the issue touches on long-standing tensions.

Town leaders objected to the bill and told the Legislature it would “deprive the Town of Perry of ordinance-making authority.”

Wabanaki leaders celebrated it, both as a partial recognition of tribal sovereignty, and as a major step toward solving the reservation’s water problems.

The application to place the land in trust was submitted earlier this year, and Bassett, the chief, said the tribe will not continue work there until it is approved.

If that well can produce a clean, reliable municipal water supply — something that remains an open question — it’s not clear whether Sipayik residents will trust it.

Every time the district has managed to keep the water clear and pure for a stretch, a spike in TTHMs or a period of discoloration sends confidence plunging, Longfellow said. He describes the community as “hypercritical” of its water.

Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness distributes bottles of clean water every Wednesday by the dock for residents to drink and cook with.

In 2017, the tribe bought land across from the elementary school with a drilled well and in 2022 opened the Samaqannihkuk Well to the public. A spigot there capable of producing 20 gallons per minute of safe, clean drinking water is free to use.

A ticker inside the wellhouse marks 178,000 gallons of water, tested and confirmed to meet federal and state drinking water standards, collected.

“Even the well water, I filter that with a Brita filter,” Bassett, the spry octogenarian, said.

Smith, who used to haul jugs of water to wash her daughter in the sink rather than run a bath, is similarly cautious.

Officials consider a new groundwater source for the district essential.

“I’d still want to see the tests — the proof,” Smith said. “And it would have to come from somebody within the community that I trusted that was doing the work and doing the testing.”

Reuben M. Schafir is a Report for America corps member who writes about Indigenous communities for the Portland Press Herald.

We invite you to add your comments. We encourage a thoughtful exchange of ideas and information on this website. By joining the conversation, you are agreeing to our commenting policy and terms of use. More information is found on our FAQs. You can modify your screen name here.

Comments are managed by our staff during regular business hours Monday through Friday as well as limited hours on Saturday and Sunday. Comments held for moderation outside of those hours may take longer to approve.

Join the Conversation

Please sign into your CentralMaine.com account to participate in conversations below. If you do not have an account, you can register or subscribe. Questions? Please see our FAQs.