After years of decline, the number of confirmed cases of the physical abuse of children in Maine has climbed dramatically in recent years – much higher than the national average.

Those who work with abused children say they’re not sure why the numbers are spiking, but there is evidence that a surge in opiate drug abuse may be a contributor, as well as the lackluster economy and high-profile cases that spur more people to report abuse.

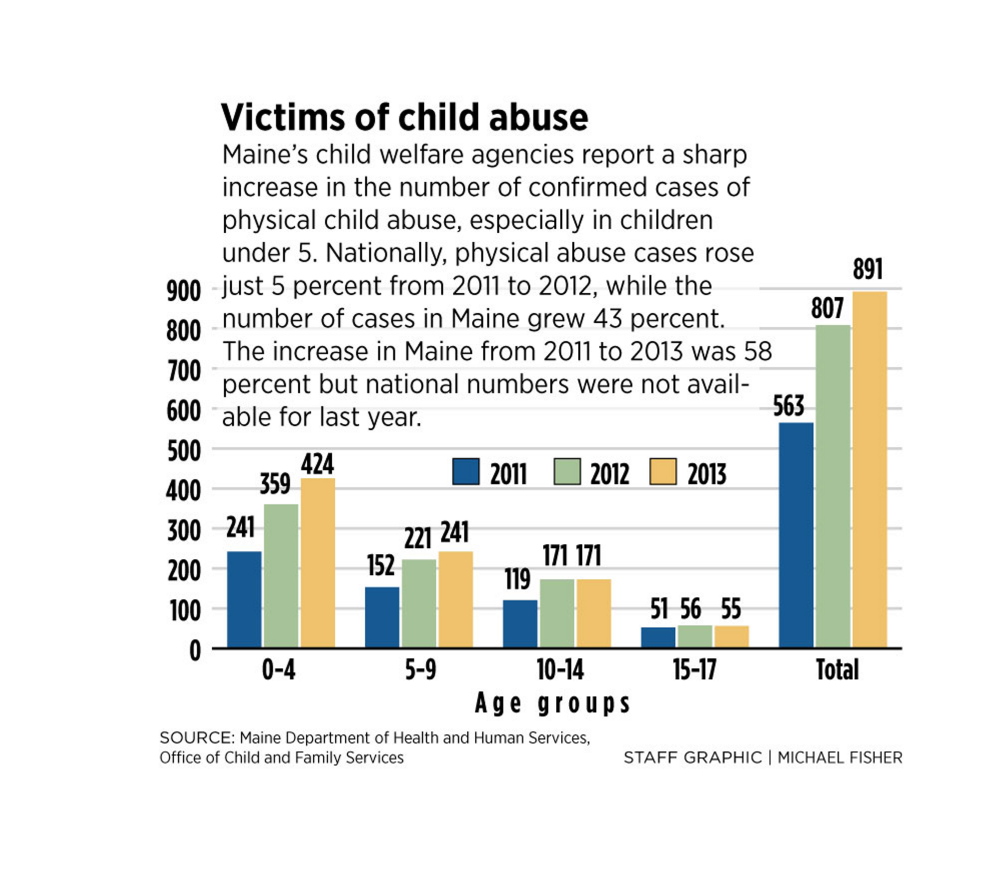

Confirmed cases of the physical abuse of children in Maine rose by 58 percent from 2011 to 2013, a reversal of a decline, both in Maine and nationally, over the previous two decades.

Physical abuse numbers nationally went up just 5 percent from 2011 to 2012, the latest period for which state-by-state numbers were available, while in Maine they jumped by 43 percent. Only Utah, Oklahoma and Montana had higher rates of increase.

The increase in Maine cases was even greater for children younger than 5. Those cases climbed from 241 reported in 2011 to 424 last year, a 78 percent increase, according to data provided by the state Department of Health and Human Services.

“These are big changes in the state. They’re huge, actually,” said David Finkelhor, director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire.

The number of cases involving serious abuse also has risen, according to child safety advocates and state officials.

“Statewide, staff are seeing babies being beaten like they’ve never seen before,” said Therese Cahill-Low, director of the Office of Child and Family Services at DHHS. “Some of these (staff) people have being doing this for 20 years and are significantly impacted by abuse they’re seeing now and how horrendous it is.”

Confirmed cases of physical abuse dropped by 54 percent nationally between 1992 and 2012, while cases in Maine declined by 15 percent, the Crimes Against Children Research Center reports.

It can be difficult to tell how much of the growth is attributable to more abuse and how much stems from better reporting procedures, according to researchers and advocates.

“When you see changes that are that big … you also want to know if anything might be affecting it in terms of the definitions or data collection. Are they doing a lot of training?” said Finkelhor, who credited Maine for publishing its abuse numbers, which has not always been the case. “It seems to me likely there is some actual increase going on, too.”

Cahill-Low said the state has not added caseworkers or changed its definition of abuse. The agency’s caseworkers say they have seen an actual increase, particularly in severe abuse, she said.

RESPONSE HARD TO GAUGE

DHHS said there are more cases of emotional abuse and neglect than physical abuse of children in Maine, but those cases have not increased nearly as much. The number of cases in 2013 of child neglect was 2,796, the number of cases involving emotional abuse was 1,417, and the number of sexual abuse cases was 239. All of those numbers were lower than the previous year.

Gauging whether law enforcement or protective services have stepped up their actions in response to the increased cases of physical abuse is difficult: Data maintained by the Administrative Office of the Courts on criminal convictions isn’t broken down by age for simple assault or aggravated assault, although there is a separate charge of simple assault when the victim is younger than 6. The office was unable to provide numbers on how often people are charged in that category.

Geoffrey Rushlau, district attorney for Sagadahoc, Lincoln, Knox and Waldo counties, said the number of simple assault charges for a victim younger than 6 would be a fraction of the total number of physical abuse cases. A Bath man accused Thursday of assaulting his 8-week-old son, for instance, was charged with aggravated assault, domestic violence assault and endangering the welfare of a child.

Numbers on children removed from an abusive home have risen in recent years. The state removed 995 children for abuse or neglect in 2013, up 57 percent from the 634 removed in 2011, which was the lowest number in the previous six years. In 2008, the state removed 856 children from their homes because of abuse or neglect.

Physical abuse was cited in 16 percent of those removals last year and 17 percent in 2011. In the last year, the main reason cited for removing a child was neglect, at 84 percent, followed by drug abuse by a parent at 46 percent. More than one cause can be cited in a removal.

Sometimes, caseworkers initiate an intervention because of physical abuse, but other issues – such as substance abuse, domestic violence or mental illness – can end up being a primary cause for removing a child, Cahill-Low said.

In response to a request from the Portland Press Herald, the DHHS released statistics last month on Maine child abuse cases after an assault on twin infants in Sanford. Their father, Anthony Carpinelli, 21, has been charged with aggravated assault after his children, Willow and Haiden, who were 2 months old at the time, were hospitalized with head injuries. Both of the children were discharged from the hospital a few days later.

Carpinelli is being held at the York County Jail on $25,000 bail. The York County district attorney’s office said the case remains under investigation and has barred DHHS from releasing its report into allegations of abuse against the infants.

MORE CASES REPORTED

While still a small percentage of overall child abuse numbers, cases of abusive head trauma and hospitalizations are on the rise and are much higher in Maine, per capita, than other states.

Dr. Lawrence Ricci, a forensic pediatrician with the Spurwink Child Abuse Program, said there have been 14 cases of abusive head trauma involving children younger than 1 in the last year. National rates would suggest a state with Maine’s population would have about five such cases. Another nine children younger than 1 year old were admitted to a hospital for other serious injuries that could lead to severe disabilities and years of therapy and medical procedures.

A high-profile case, such as the death of 10-week-old Ethan Henderson in Arundel in 2012, prods health care professionals and child care providers to be more aggressive in reporting suspected abuse.

In that case, Ethan’s father was accused of squeezing the baby’s head hard enough to cause critical brain injuries. The baby had been taken to a doctor six weeks earlier for an arm fracture, though there was no indication that a report was made to the state’s child protective agency at that point.

That case served as a painful reminder to those who are mandated to report suspected child abuse of the potential consequences of not reporting. Advocates say the case and others like it could have led to more reports of abuse that might have gone unreported previously.

Finkelhor said a similar phenomenon led to an increase in reported sexual assaults on children when Pennsylvania State University assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky was charged in 2011 and later convicted of dozens of counts of child molestation.

A new law approved by the Maine Legislature a year ago mandates that anyone required to report possible child abuse to the state automatically do so whenever a child under 6 months of age has a broken bone, substantial bruising, burns or poisoning, on the reasoning that children that young cannot walk and are largely incapable of injuring themselves in such a way.

Teresa Huizar, executive director of the National Children’s Alliance, said that one or even two years of abuse numbers for a particular state may be an anomaly and it is more useful to examine long-term trends and factors, such as the impact of the recession.

Huizar said that instead of leaving children in licensed day care facilities, children were sometimes left with neighbors, friends or extended family during the recession.

“They were seeing high levels of kids coming into emergency rooms for physical abuse,” she said. “It’s not just that families are under more financial stress and lash out, but kids were being left in care they otherwise would not have been.”

DRUG USE ON THE RISE

Another problem that’s growing in Maine could be one contributor to the increase in child abuse numbers.

Child abuse numbers are rising at a rate similar to the increase in overdose deaths, the frequency that babies are born to drug-using mothers and the number of children accidentally ingesting drugs or medication for drug treatment, according to Dr. Stephen Meister, a pediatrician who chairs the state’s Child Death and Serious Injury Review Panel.

“What we’ve had is a dramatic increase in opioid use in our young adult population,” Meister said. Federal data indicate that Maine has one of the highest rates of opiate abuse – including prescription painkillers and heroin – in the country.

Research shows that children in homes where parents are actively using illicit drugs are much more likely to be abused than children in families without regular drug use, Meister said, citing a 2009 Australian study which found that 51 percent of infants born to substance-abusing mothers warranted intervention by child protective services, mainly for physical harm or risk, compared to 6 percent born to mothers who didn’t use drugs. Children of parents following a drug treatment program are more likely to be abused than children of parents who haven’t used drugs, but less likely than in families with active drug users, he said.

The role that drug use plays in child abuse can vary. In some cases, drug-affected parents are incapable of caring for their children, leaving them vulnerable to abuse. In others, drug abusers going through withdrawal can’t handle the stress of a child in the house. Children of active drug users are also more likely to have developmental needs, making them more challenging.

“I think sometimes families react to a point where a crying baby is a little too much and make decisions impulsively based on that,” Cahill-Low said.

State social workers may try to come up with a safety plan in such cases, but often the state is unaware of any danger until after a severe episode of abuse, Cahill-Low said.

The state has tried to emphasize more reporting by health care workers when babies are born drug-dependent.

There were 927 babies born in Maine in 2013 classified as drug-affected, according to the DHHS, an increase of 39 percent over 2011, when 668 drug-affected babies were born.

Meister notes that drug use is not an automatic predictor of child abuse. Less than half of the cases in which babies were born drug-affected led to an intervention by the state.

Cahill-Low said she communicates with her counterparts in other New England states who also have seen an increase in drug-related child abuse. Based on their experience, she expects physical abuse will continue to increase through this year.

“The more abuse and neglect you experience as a child the greater the risk you will become involved in substances and become a drug addict or an alcoholic,” Meister said. That increases the chances a person will abuse his own children.

“This becomes multi-generational,” Meister said. “We parent the way we were parented.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.