SOUTH PORTLAND — Sally Davis was one of many voters who felt overwhelmed by all the expensive political advertisements leading up to Tuesday’s election.

So, Davis, a 53-year-old musician and teacher, stood outside the polls on Election Day and asked neighbors to help do something about it — amend the U.S. Constitution, to be exact.

“I think we’re just tired of so much money being wasted,” Davis said. “Our representatives are not really representing us, they are representing major corporate interests.”

The 2012 election season shattered records for political spending in Maine and across the country. Final totals won’t be known for a while, but an estimated $6 billion was spent nationwide, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonprofit that tracks campaign finance reports.

The flood of cash is fueling momentum to clamp down on money in politics, from state and federal legislation to a constitutional amendment that says freedom of speech should not include unlimited, anonymous political spending.

Real change is far from a sure thing, however.

Reforms have repeatedly stalled in the hyper-partisan Congress, where efforts to regulate political speech are usually seen as favoring one party over another. Amending the U.S. Constitution, meanwhile, is a monumental task that requires approval from three-fourths of the states.

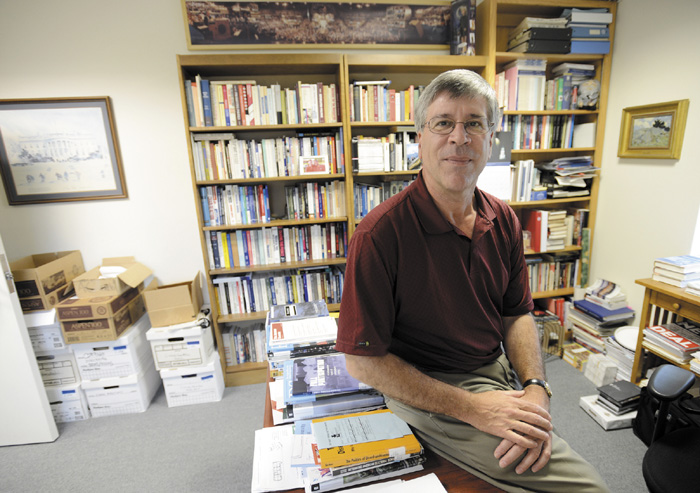

“It’s very clear there is wide popular support for doing something about the campaign finance system and the amount of money in that system. The difficult thing is finding some consensus about what should be done,” said Anthony Corrado, professor of government at Colby College in Waterville.

Davis was one of 200 volunteers who stood outside polling places around the state last Tuesday, collecting signatures on small postcards that call for the Maine Legislature to formally support a constitutional amendment. Maine Citizens for Clean Elections, the group that organized the effort, collected more than 10,000 postcards statewide last Tuesday, its director said.

The effort is aimed at overturning recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions, including Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, that effectively removed state and federal restrictions on political spending by outside groups such as so-called super PACs, nonprofit organizations, corporations and labor unions.

While previous Supreme Courts ruled that such spending could be regulated to prevent corruption in politics, the current Supreme Court’s rulings say the greater danger is government restrictions on speech, including political speech.

“There’s a difference between (paid) political speech and free speech,” said Andrew Bossie, executive director of Maine Citizens for Clean Elections. Political speech is now a freedom that belongs only to the very wealthy, he said.

“We talked to a lot of voters on Election Day, and people are disgusted by the amount of money spent by outside groups to try to sway elections,” he said. “We don’t have enough money to pay for the important priorities of today, but we have this money to spend on elections.”

The presidential election will exceed $2 billion — easily a record — when all the counting is done. Even spending in the battle for control of the Maine Legislature — more than $3.4 million — shattered the old record set two years ago — $1.5 million.

Maine’s U.S. Senate race totaled more than $11 million in total spending by the candidates and outside groups. And the result — Angus King winning with 53 percent — was exactly where polls said the race stood in June, before the candidates and outside groups launched the advertising war.

Maine’s 2012 Senate race did not set a state record — about $17.5 million was spent in the 2008 Senate race. Nevertheless, it was one of the most expensive in state history despite the fact that the race was never really close, with King leading in the polls by a wide margin from start to finish. And, while most Senate races go on for a year, the Maine race only began in February when Sen. Olympia Snowe, R-Maine, made her surprise retirement announcement.

“It was a very atypical race,” Corrado said. “In a more typical Senate race, there would have been far more (money).”

Bossie said Maine Citizens for Clean Elections supports state and federal legislation to require more disclosure so voters know where all the money is coming from. But, he said, the amount of money is such a fundamental threat to democracy that it is time to change the Constitution so the donations and spending can be restricted.

“If you’ve got someone dumping millions of dollars into a campaign and you know about it, you still have to ask if (elected officials) represent them or the constituents,” Bossie said.

Bossie said any constitutional amendment must restore the ability of Congress and the states to regulate political fundraising and spending.

Other groups are involved in similar grassroots efforts around the country. Nine states have formally expressed legislative support for an amendment, Bossie said, and he hopes Maine will be the 10th. So far, 23 cities and towns in Maine have passed resolutions supporting the effort, including Portland, Bangor, Waterville and Scarborough, Bossie said.

Lance Dutson, a Republican political strategist who most recently managed Charlie Summers’ Senate campaign, said the idea of allowing the government to narrow the definition of free speech is dangerous.

“When you start talking about a flaw in the First Amendment of the Constiution, you are on pretty thin ice,” Dutson said. “The subjectivity of whoever is in charge being able to decide what is political speech and what isn’t is a perilous place to be.”

Dutson also argues that the money, and the advertisements it pays for, are not a threat to democracy.

“The point that needs to be made is that money may be speech, but it’s not a vote,” he said. “Unless you believe there is an innate inability of human beings to exercise their will because of the dominance of paid media, a vote is a vote.”

Corrado, the Colby professor, has been tracking and studying the explosion of secretive political spending around the country.

He said the idea of a constitutional amendment is clearly mobilizing support for some kind of reform, but it does not seem realistic.

“There are widespread differences in terms of what an amendment would look like, and the hurdles for getting an amendment are especially high,” he said.

For example, a narrow amendment that says corporations do not have the same free speech rights as people do would not have affected most of the money that flowed into the 2012 elections from wealthy individuals, super PACs and nonprofits. And drafting a broader amendment could have unintended consequences for free speech rights, he said.

Corrado said the most achievable reform would be a new law requiring more transparency.

“I think the first step is that there has to be progress made on disclosure and informing the public about the sources of funding,” he said.

In the meantime, Corrado said, it’s not likely that the cash will stop flowing.

“We’re in a pattern now where there is a battle for partisan control, whether you are looking at Congress or you are looking at the state Legislature,” he said. “Those battles are going to be very expensive.”

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.