GARDINER — Federal, state and local officials sat down at a conference table in this riverfront city more than a year ago to consider how to make Gardiner’s historic downtown resilient to floods.

Part of that answer might lie in a report, issued on Friday, that provides an assessment of how buildings in Gardiner’s downtown could be protected from flooding. But the larger question of how the federal government plans to respond to natural disasters like floods remains uncertain.

Unusual midwinter flooding along the Kennebec River this year has put the issue front and center.

The National Flood Insurance Program, which provides flood insurance for buildings with federally backed mortgages in identified flood plains, was already $25 billion in debt before a series of devastating hurricanes struck the United States last summer. And the program’s reauthorization, scheduled for the end of last September, has been delayed and the program’s funding has been tied to a series of continuing authorizations voted by Congress to keep the federal government operating.

For now, some communities are forging their own path.

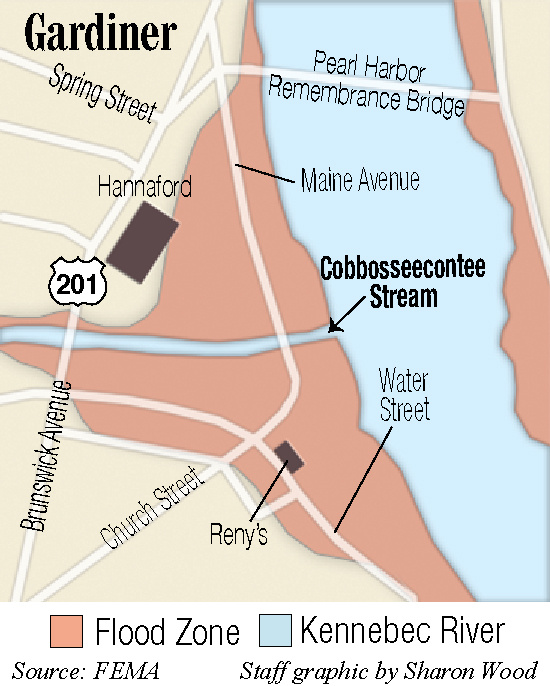

At the end of November, a group of experts toured a historic block of buildings on Water Street in Gardiner, taking photos and making measurements. The buildings are owned by Gardiner Main Street, acquired from Camden National Bank for $1 in November 2016.

The community development organization has offered the buildings up as part of a pilot project to show how existing historic buildings can be made more resistant to flooding.

The assessment, completed by the Maine Silver Jackets program, part of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, may help determine what measures could be taken.

“The Downtown Master Plan and the Comprehensive Plan recognizes the threat of flooding exists,” said Patrick Wright, executive director of Gardiner Main Street.

“There’s no specific flood mitigation plan, and there has been no coordinated, dedicated effort to deal with flood mitigation,” Wright said.

HISTORY OF FLOODS

With or without mitigation plans, the Kennebec River has flooded, generally in the winter or spring, often as the result of a combination of factors — ice break-up, snow melt or rain.

Earlier this year, a brief mid-January thaw and heavy rain shifted ice in the Kennebec River, resulting in an ice jam and destructive flooding along Hallowell’s low-lying waterfront, submerging cars and washing river water into the lower levels of buildings closest to the river.

In Augusta, city police closed the parking lot behind Water Street on the river’s west bank as a precaution.

For weeks, state and county emergency management agencies monitored river conditions as the ice jam settled in. Twice, the Maine Emergency Management Agency requested ice-breaking operations by the U.S. Coast Guard to break up sheets of ice in the river so that when the jam started to break up, the chunks and slabs would have a place to go.

The Coast Guard’s first attempt at the end of January was halted because the ice was too thick in places and the broken ice didn’t flush down the river. The second attempt, about a month later, opened up the river south of Gardiner, and the jam slowly broke up and flowed down the river.

While the flooding with that ice jam was relatively minor, other break-ups have been much more serious.

In mid-March 1936, rain started falling as ice was breaking up on the Kennebec, and when it all started flowing, chunks of ice scoured everything they touched. Historic photos capture in black and white the damage to bridges in the Kennebec River system, including the bridge that linked Dresden and Richmond, torqued and twisted off its supports and carried downriver.

But the largest of the Kennebec River floods — in fact, the largest natural disaster in Maine’s history — happened 31 years ago this weekend.

The massive flood of 1987, happened after heavy rain fell across the northern part of the Kennebec River’s 6,000-mile watershed. The volume of water that moved through the region, a combination of runoff and melting snowpack, reached historic levels. At its height, the discharge rate at the river gauge in north Sidney was 232,000 feet per second.

Throughout the Kennebec River system, people were stranded by washed out bridges and roads and they watched as the water rose higher and faster than forecasters could calculate. In Augusta, where the flood stage is at 13 feet, the river crested at 34 feet.

In the wake of the flood, the Maine Emergency Management Agency reported that 2,100 homes were flooded; 240 sustained heavy damage and 215 were destroyed. Four hundred small businesses were affected.

In Winslow, the historic Fort Halifax that had stood at the junction of the Sebasticook and Kennebec rivers since 1754, was swept away,

At the time, the damages were estimated at $100 million, an amount that would be more than twice that today.

LOOKING AHEAD

Today, economic and community development officials are at a crossroads, and the way forward is not entirely clear.

In communities like Gardiner, Hallowell and Augusta, historic downtowns grew up along the edge of the river, which were transportation and trade corridors long before the first highway was ever built.

It’s those areas that they recognize as assets in community and economic development efforts.

“Historic buildings in the flood plain that need rehabilitation are already challenging enough to rehab to support economic and community growth,” Wright said. “Adding flood mitigation on top of that stacks the cards against us, and the reality of where flood insurance rates are going stacks the cards against us.”

But the cost of doing business in the flood zone is rising and no one knows how high.

The National Flood Insurance Program was created nearly five decades ago to provide affordable insurance to people with properties in flood zones and for the most part, what people paid in to the program funded the claims that were paid out.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Superstorm Sandy less than decade later drove the program into debt with combined losses of $28 billion. To cure it, premiums that the federal government has subsidized for many policyholders for decades are on track to be increased until the debt is erased.

Those changes, Wright said, are providing some incentive to consider flood mitigation efforts more carefully.

Often, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which administers the flood insurance program, opts to buy flood damaged properties, allowing people to relocate.

In Winslow, where the Kennebec took Fort Halifax 31 years ago, it also took seven buildings on the water side of Lithgow Street and Bee’s Snack Bar, which has been rebuilt.

“Those lots were purchased,” Winslow Town Manager Michael Heavener said, “and they are forever wild.”

The total value of those properties at the time was $51,200, according to the town’s assessing records, he said.

In his time with the town of Winslow, Heavener said the Kennebec has reached the flood stage, and on at least one occasion, it crested Lithgow Street but it didn’t threaten any structures. And it hasn’t prompted concern from town residents.

‘IT’S A CONUNDRUM’

Downriver, the concerns are more focused.

The expected insurance program reauthorization did not take place in September as expected; rather it was folded into the continuing resolutions that the U.S. Congress passed and President Trump signed to keep the federal government operating. The current deadline for reauthorization is now July 28.

Rather than wait, Gardiner officials are pushing ahead.

At the end of November, a team of experts from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers toured five buildings that Gardiner Main Street owns.

The Silver Jackets team brings together agencies at all levels of government to develop strategies to reduce the risk of floods and other natural disasters. The team’s job was to make an assessment of the measures that could be taken to protect the buildings from the flooding that scientists say is inevitable.

“It’s a conundrum a lot of downtowns face,” Brian Balukonis, one of the Silver Team members, said during the review.

One of the typical measures to protect buildings is to raise them on stilts to lift them out of the flood plain, and another is building levies to control the path of flood waters. Neither is practical for historic downtowns on the Kennebec,

The option that might work in Gardiner is wet flood-proofing.

“You allow the water to come in and go out, and you make sure that everything below the 100-year-flood level is waterproof,” he said.

The other, which the report released Friday recommends is dry flood-proofing, which calls for sealing building walls with waterproofing materials that will prevent water from getting into the structures.

The state Historic Preservation office has offered two grants to help building owners in downtown Gardiner obtain flood elevation certificates so they can identify how high the water in a statistical 100-year-flood might reach, so they know where they have to take flood mitigation measures.

“We view the flood elevation certificate as phase one of a mitigation plan,” Wright said.

Once that data is collected, it can be entered into a geographic information system to develop information that, among other things, will be useful to investors. Wright said a second grant from the historic preservation office will help make that happen.

“After you identify that, if you have taken measure to flood-proof your building, your insurance premium should be the same as that of someone who is completely out of the flood plain,” he said.

Jessica Lowell — 621-5632

Twitter: @JLowellKJ

Comments are not available on this story.

Send questions/comments to the editors.